The Outdoor Gear I’ll Never Throw Away

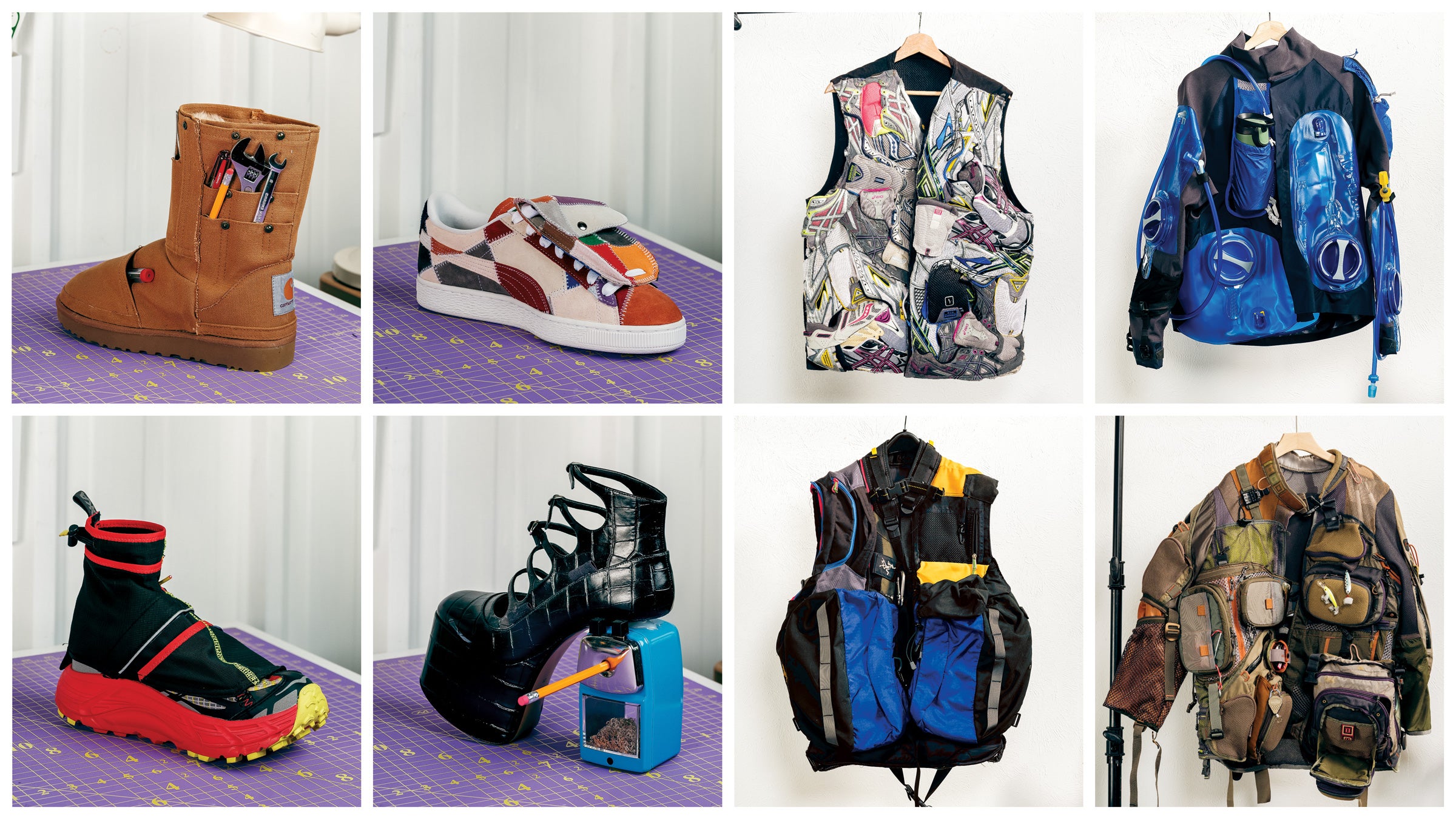

Nicole McLaughlin's designs range from a jacket crafted out of upcycled water reservoirs (top right) to a high-heeled shoe equipped with a fully operable pencil sharpener (second from bottom left). It's just one way to get more life out of old gear. (Photo: Ben Rasmussen)

Black Friday is coming, which means my inbox is already filling with subject lines promising 40 percent off technical shells and limited-edition colorways of packs I don’t need. The algorithms know me well enough by now—they’ve clocked my abandoned carts and my weakness for a good gear story. And yet, when I actually need to grab something for a day hike or a quick trip to the corner store, I reach for the same beat-up Arc’teryx Arro day pack I’ve had for more than twenty years.

It’s not that I’m above consumerism. Like all of us at Outside, we live and breathe gear. I’ve bought plenty of things I didn’t need, seduced by promises of lighter weight or better weatherproofing or something that will magically keep me cooler or warmer. But this particular pack—well–worn, with plenty of life to go—has achieved something that new gear never can: it’s become an extension of my body.

I know where every zipper is without looking. The main compartment is just large enough for a book, a water bottle, and a layer, but not so big that I’m tempted to overpack. There’s a discrete hip belt for when I might have overdone it with the granola and trail mix or acquired some things at the corner bodega. It’s traveled with me through enough years and enough places that using it feels less like wearing gear and more like putting on my own skin.

Nicole McLaughlin, whose upcycling work we profiled in the Fall Style + Design issue, understands something essential about the relationship between objects and memory. When she transforms old gear into new forms, she’s not just being clever about sustainability—she’s honoring the fact that worn equipment has a soul. It’s been places. It’s done things. The stains and tears aren’t flaws; they’re autobiography.

My Helly Hansen Odin mountaineering pants tell their own story. The waterproofness has mostly given up, worn down by too many days in conditions they were actually designed for. They’re no longer suitable for anything serious—a proper alpine mission or even a sustained rain—but they’re perfect for sledding with my kids, for winter hikes where the real threat is wind rather than wet, for that in-between weather when you need coverage but not full protection. They’ve been demoted from technical gear to household workhorse, and somehow that feels right. They’ve earned their retirement into casual use.

Then there’s the Osprey pack—slightly bigger than the Arc’teryx, light enough to forget you’re wearing it, capacious enough for a laptop. For a few years, it doubled as a diaper bag, which is maybe the most intense field testing any piece of gear can endure. It survived emergency snack deployment, and that particular brand of chaos that comes with schlepping small humans around the city. Now that the kids are older, it’s returned to its original purpose: a do-everything pack for when the Arc’teryx is too small but a full hiking pack is too much. It still has Cheerio dust in the bottom seams that I can’t seem to get out.

In Brooklyn, where I live, you see branded totes everywhere. I’m not a big tote guy, which means I need bags that can handle actual weight and weather without looking like I’m about to summit something. These pieces—let me move through the world with the things I need without announcing what I’m doing. It’s gear as quiet competence.

The tension, of course, is that I write about new gear constantly. I celebrate innovation. I understand that materials science has improved, that today’s fabrics breathe better and weigh less and last longer than what I’m clinging to. For anything truly demanding—a long backpacking trip, a technical climb, conditions where failure means discomfort or danger—I reach for the real deal, latest and greatest equipment. I’m not romantic enough to pretend that sentimentality trumps performance.

But for the daily texture of an outdoor life—the dog walks, the coffee runs with a book, the spontaneous afternoon hikes in Prospect Park—I want the stuff that already knows me. The gear that’s shaped itself to my habits, that’s been broken in by repetition rather than design. There’s a difference between consumption and conservation, sure, but there’s also a third category: continuation. The choice to keep using something not because you can’t afford to replace it, but because replacement would mean losing something that can’t be quantified in specs.

When the Black Friday emails arrive, I’ll probably click on a few. I’ll add things to my cart and then close the tab. Maybe I’ll even buy something. But the Arc’teryx pack will still be hanging by the door, ready for whatever comes next, accumulating new stories on top of the old ones. That’s the thing about gear that won’t die: it becomes less about what it does and more about what it knows. And what it knows, at this point, is me.