If you buy through our links, we may earn an affiliate commission. This supports our mission to get more people active and outside.Learn about Outside Online's affiliate link policy

How My iPhone’s New Satellite Messaging Function Kept Me Connected in the Backcountry

(Photo: Alex Hutchinson, Abigail Wise)

Shortly after sundown on July 29, I found myself on a stony beach at the extreme northern end of Vancouver Island, holding my phone above my head and pointing at an indeterminate point in the sky. Around me, three other people were doing the same thing. One of them had just been alerted via satellite message that a massive earthquake off the coast of Russia had triggered a tsunami warning for the entire west coast of the island. Now we were frantically trying to determine whether we needed to abandon our tents and flee into the rainforest.

Last fall, Apple debuted a new feature on its most recent phones (iPhone 14 and later): when you have no cellular coverage, you can send iMessages and regular text messages via Globalstar’s constellation of 25 satellites. I was already planning my family’s seven-day hike along Vancouver Island’s North Coast Trail for the summer of 2025, and intended to buy a Garmin inReach for emergency communications via satellite. But Apple’s announcement made me reconsider. In June, I swapped my old iPhone XS for a new iPhone 16 specifically to get satellite messaging for a couple of backcountry trips this summer. Here’s how it went.

Getting Connected

My biggest worry was that I’d get into the wilderness and then discover that the feature didn’t work as expected. There’s been plenty of online chatter about whether the iPhone’s satellite functionality might be a suitable replacement for dedicated satellite messengers, but very few first-hand reports.

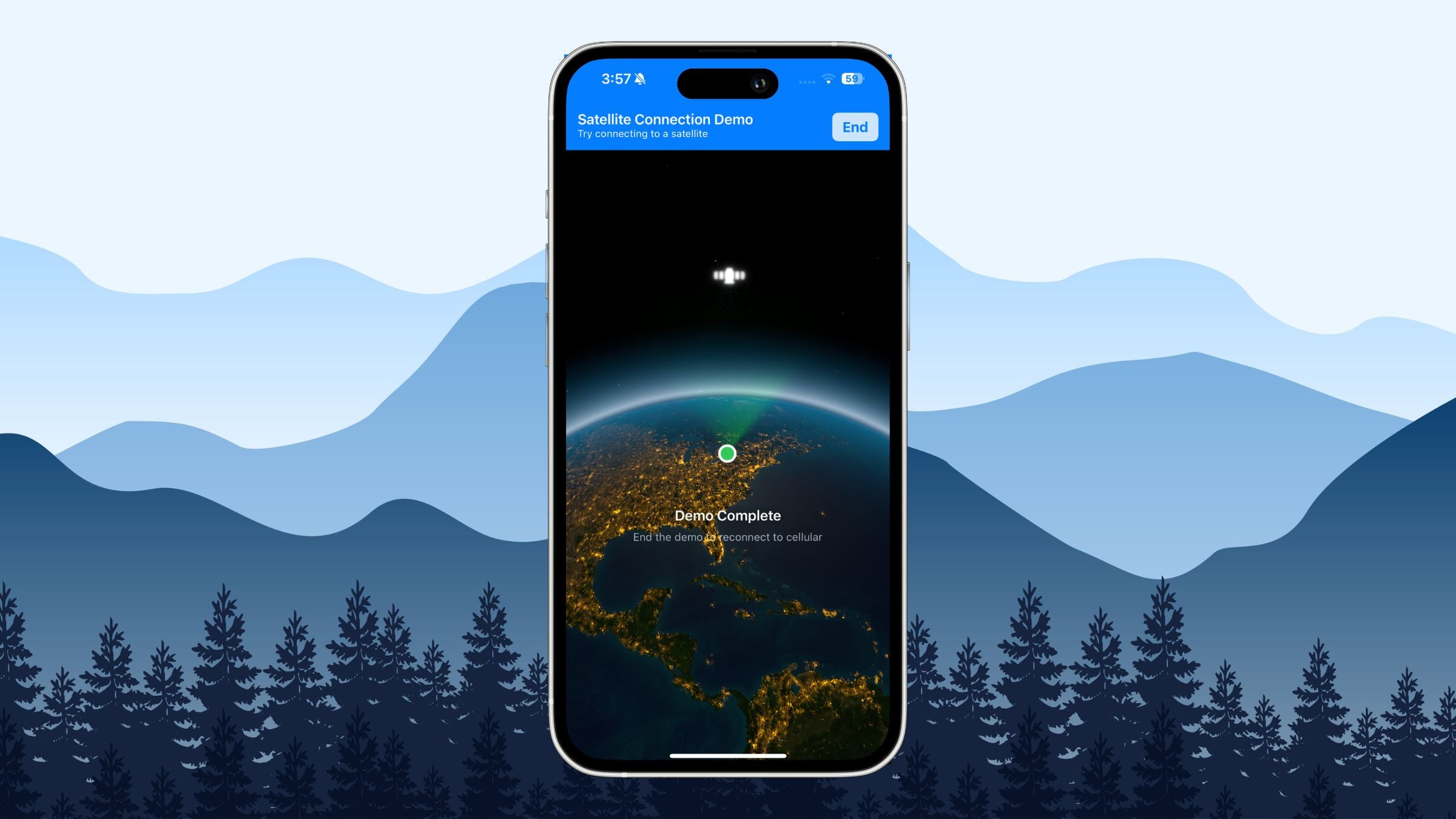

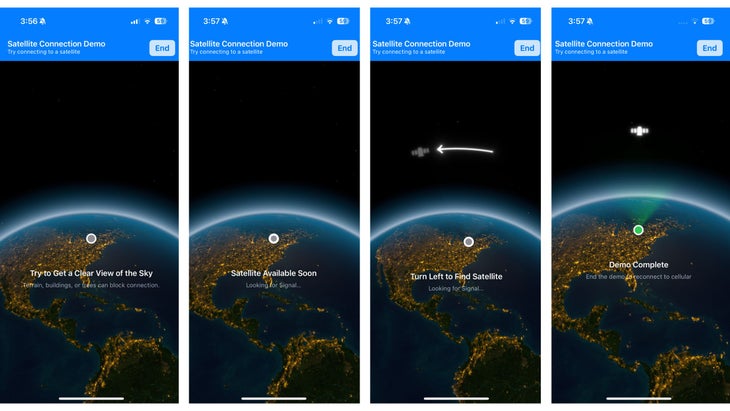

You can’t send satellite messages when you have cellular coverage, but there is a feature that enables you to practice connecting to a satellite. Open Control Center by swiping down from the top right, tap the cellular icon on the righthand margin, choose Satellite then Try Demo (further instructions here). You’ll end up with a picture of the globe with a satellite in the sky above, showing you which direction to point the phone, or else a message telling you how long until the next satellite is available. It’ll tell you when you’re successfully connected. Doing that a few times before I left on the trip reassured me that I knew what to do.

Once I was actually off the cellular grid, the process was even easier. As soon as you open the Messages app, the phone asks whether you’d like to connect to a satellite, and a Satellite menu appears in the Settings app below Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, and Cellular.

There are various details about who exactly can receive messages from you—to receive satellite iMessages, your contact needs at least iOS18. Anyone with a non-Apple phone (or an iPhone with iOS 17.6 and up) can receive regular SMS texts. For backcountry safety purposes, I don’t really care whether I can send emojis, so SMS is fine. There is one important note: you won’t receive messages from other people via satellite unless you’ve already sent them a satellite message or if they’re listed among your emergency contacts (which, strangely, is done through the Health app). This is something that’s definitely worth doing before you leave on a trip, so that your loved ones can send you, say, unexpected tsunami warnings.

I played around with satellite messages after dinner on our first night hiking on Vancouver Island, and successfully sent and received messages with various people on new and old iPhones as well as Android phones. Sending a message takes about 30 seconds, but replies came promptly. You need a clear view of the sky, which was easy at beach campsites but tricky when hiking through dense forest.

Comparing to the Competition

I’ve used a wide variety of emergency communication devices over the years. The simplest is a personal locator beacon: you press a button, and it starts broadcasting your location to emergency rescue teams. That’s great as a last resort, but lacks nuance.

On a canoe trip down the Yukon’s Snake River one year, we reached our designated float plane pick-up spot only to find a forest fire burning on the banks of the river. A personal locator beacon wouldn’t have helped us much. Fortunately, we had a satellite phone, so we were able to speak to the pilot, who reassured us that the fire had been burning slowly for a week, and we could safely camp there for the night. Then a storm rolled in and prevented the plane from flying, leaving us stranded on the river for an extra day and night with a few sausage ends and some bannock to sustain us. We were very glad to have the sat phone for updates.

In recent years, we’ve started to use a friend’s Garmin inReach on trips. It’s been a great intermediate option, with two-way communications at a better price point. The inReach is rugged, has great battery life, and also provides weather forecasts. I was a convert, until the option of using my phone arose.

The iPhone definitely isn’t a perfect substitute for an inReach or other dedicated satellite messengers from companies like Spot, Motorola, and Zoleo. It’s less rugged, and has far less battery life—especially if, like me, you’re also using the phone as your primary camera. I brought a 10,000 mAh power bank with me, which should give me about three full recharges. In the end, by keeping the phone in power-saving and airplane modes, I only had to recharge it once over the course of seven days.

The satellite coverage also isn’t as comprehensive. The gold standard here is the Iridium network, which has 66 active satellites and is what the inReach uses. An Apple spokesperson told me that the Apple satellite service is only available in the United States, Canada, and Mexico. The company’s support pages also note that it might not work above 62 degrees latitude, which includes the northern parts of Alaska.

The Verdict

For my purposes, as a recreational-but-not-too-extreme backcountry tripper, the iPhone does the job. The biggest advantages for me are eliminating an extra device to carry, and the price: satellite messaging is free for two years after the activation of the phone. Apple hasn’t yet announced what the pricing will be after that. To be honest, I hope it’s not too cheap, or at the very least not free.

Back in 2013, when the inReach was new, I wrote an article lamenting the demise of blank spots on the communications grid. One of the great joys of my backcountry trips is seeing that last bar of cellular service disappear, and knowing that the outside world no longer has its tentacles around me. The safety benefits of satellite messaging are so clear that I can’t convince myself not to take a device with me. But I still resent the connectivity. That’s why I hope there’s at least a nominal price barrier that will help me limit my own use of satellite messaging to important situations, rather than spending my evenings around the campfire responding to idle banter from friends back in the city.

You could even argue that my hike on Vancouver Island would have been more peaceful if none of us had ever received that tsunami alert. It was late in the evening, long after my friends and family back on the east coast had gone to bed, so I struggled to get updates. Eventually, one of the other people camping on the beach managed to reach a friend who reported back that the size of the wave was expected to be less than a foot. A few people who had set up on the beach itself moved their tents up into the forest, where my tent was already set up.

The trade-offs remind me of the debate about early medical screening tests: you get advance warning of possible problems, but the price you pay is a bunch of false alarms. I was glad to have satellite connectivity on my trip, and I’ll keep using it on future trips. But when I went back to my tent that night, after reassuring my kids that we were going to be OK, I turned my phone off before going to sleep.

For more Sweat Science, join me on Threads and Facebook, sign up for the email newsletter, and check out my new book The Explorer’s Gene: Why We Seek Big Challenges, New Flavors, and the Blank Spots on the Map.