The Outside Lab Did a Lot of Testing in 2025. Here’s What We Learned.

What We Learned in the Lab

Working in any scientific field means continuous learning, and being in the Outside Lab at CU Denver is no different, no matter how much fun we’re having popping sleeping pads or overstuffing backpacks. This year, we put over 150 pieces of gear through the wringer using controlled, repeatable experiments to test their performance limits. Needless to say, we collected a lot of data points and learned a lot about the products and how different design choices affect performance.

When we weren’t purposely trying to destroy jackets, packs, and shoes, we were researching and scheming how to create our own tests to fill specific voids in the gear testing space. Along the way, we questioned if industry-standard test methods and machine setups were actually giving us results that matched real-world use. Here are our key takeaways from a year of trial and error at the Outside Lab.

Waterproof Materials Are Evolving Quickly

There are a few different standardized test methods to test waterproofness of fabrics. If you’ve ever noticed a “5K” or “15K” waterproof label on your outerwear, you’ve seen the results of one of those tests. That rating comes from the hydrostatic head pressure test—also known as the water column test—which assesses how waterproof a fabric is by using high pressure to push water through. Think standing directly under a heavy waterfall or in front of a firehose, and seeing how much water the fabric can withstand before failing.

Though it provides great data, this test is often considered overkill for a lot of outdoor gear when determining if an item is waterproof (after all, how often are you getting directly pummeled by a waterfall and putting your gear under that kind of pressure?). So instead of determining whether something is waterproof at all, we use hydrostatic head pressure in the Outside Lab to compare items in the same category for levels of waterproofness.

Advancements in materials—especially ultralight fabrics—made conducting this test exponentially more difficult in 2025. Some fabrics would burst or tear due to pressure during testing before beginning to fail from water intrusion; put another way, the fabric stretched and broke before we could analyze its waterproof limit. This makes sense, as ultralight materials often sacrifice durability to save ounces, but previous iterations would start to saturate before tearing. Now we’re seeing the opposite: fabrics used in ultralight rain shells are rivaling heavy-duty technical jackets, reaching high waterproofness levels without sacrificing breathability.

Coincidentally, we were already working on additional tests to evaluate realistic rain performance over time (to let you know exactly how long you can stay dry in a storm). These new ultralight materials have made it even more clear that we need this alternate test method. This might not sound good for the lab, but it’s why we put in the work—to find the limits and continue pushing our understanding of the gear we use. Read more about our waterproof testing on the Backpacker roundups for best women’s and men’s rain jackets.

Lesson: Ultralight materials have advanced rapidly in the outdoor gear space, offering high performance with less sacrifice than before. Our lab tests will have to evolve to keep up.

Shouldering the Load Takes on New Meaning

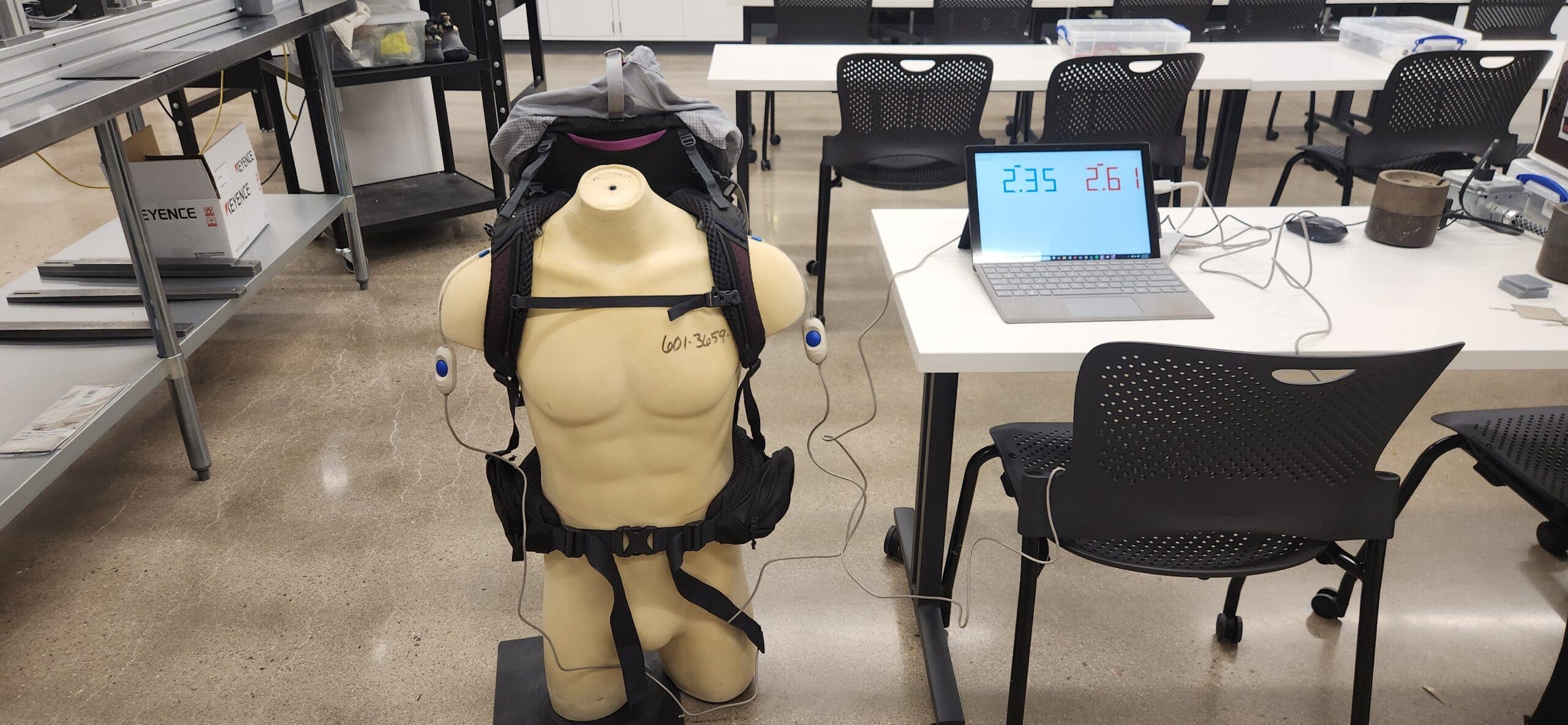

We often tweak standard test methods to better match real-world use or to replicate scenarios reported by our field testers. However, sometimes there aren’t known tests to answer the questions our gear editors and testers ask—like “how much weight can my pack really carry effectively?” To find out, we developed a test that measures the load on a mannequin’s shoulders while wearing a pack with the hip belt properly fit, as it’s continuously loaded five pounds at a time until failure. We came away with two main conclusions:

- The location of the hip belt in relation to the rest of the pack affects its ability to carry heavier loads. If the pack reaches or sags too far below the hip belt when loaded, it won’t transfer weight as well. If you often carry loads over 30 pounds, look for a pack with a construction that keeps the main body even with or above the hips.

- Though the goal of going ultralight is to carry only the essentials, but surprisingly, some UL packs can carry heavy loads just as well as the best traditional packs. Newer carbon frame stay designs and construction improvements allow these packs to handle extra heft while keeping their own weight feathery light. They might not maintain the recommended 80/20 hip/shoulder split as well through heavier loads, but these packs are still able to transfer most weight to the hips for comfortable load management.

A third and final conclusion: Lab tests that involve handling mannequins always get you weird looks from those walking past. You can find the full results of our testing on traditional packs here and ultralight packs here.

Lesson: You don’t need a burly frame to carry heavy loads; smart design and construction has just as much of an impact. Keep the load on the hips, not sagging below them.

Environment Considerations

Whether it’s rainy, humid, or freakishly windy, the outdoor environment always plays a role in field testing. Meanwhile, in the lab we’re able to control these variables, ensuring that all items in a category get evaluated under the same conditions. After a round of lab testing, we like to compare the results with field feedback to see if there are any weird discrepancies and, if so, investigate them further.

For example, when testing drying time and air permeability of the best running shirts for men and women, the highest-scoring shirts weren’t always the favorites among our runners. Instead, our testers’ ratings varied some depending on their location and typical weather.

In hot, dry climates, runners tended to prefer tops that dried more slowly to help keep them cool, but air permeability (how easily air flows through a material) didn’t factor as high in their choice. In humid climates, drying time was less important since moisture was ever-present, but high air permeability that kept air moving was key to comfort. Going into lab testing, we assumed that top marks would always equal top pick in the field. We weren’t thinking about the mechanics of how a particular shirt fabric performs in specific environments.

Lesson: Test scores and ratings can help guide your gear choice, but where you’re using it plays just as big a role.

Bringing the Outside Inside

As mechanical engineers in the Outside Lab, we’ve always known how tough it is to create tests that replicate real-world use and the outdoor environment. Standardized test methods often provide a good baseline for performance, but they also make compromises to be repeatable across multiple labs. That’s why it’s so rare to find accepted, industry-standard tests for specific performance metrics of many outdoor gear items; they’re made to be used in unpredictable and wide-ranging environments.

To fill in the gaps, many brands create their own tests to help develop products; even though the tests aren’t standardized, you can often find videos and descriptions that showcase them to highlight the work. Academic research papers can also be a source of detailed test methods for pinpointing a specific metric or mimicking certain outdoor conditions. But if that makes you think we’re well-equipped with tons of ready-to-use test methods for evaluating gear in the Outside Lab—not so.

To be honest, after we spent this year digging deeper into what’s possible, what we want to learn (for you as readers and us as engineers), and how we can grow our capabilities, we found some big gaps between standardized test methods and our actual needs. Most of the lab testing and studies being conducted today are essentially the same, with subtle differences. Field testing is essential, but repeatable tests like those in the Outside Lab can help speed up development and provide data that’s hard to find in the field.

This year, we’ve developed a few of our own tests from the ground up to address these gaps. And the more we talk to our gear editors about what information would be exciting and helpful in our reviews, the more we realize there’s a need for even more custom-created tests.

Lesson: There are more gaps to fill than we realized for science-based product testing. We’re working to fill those gaps using our resources at Outside Lab at CU Denver.

Interpreting Marketing

To really drive home the “story” of a product, marketing and packaging often focuses on a single data point from a performance test. But without understanding the test and how it’s performed, it’s easy to misinterpret the data or assume it’s much more beneficial or impactful than it actually is. Sometimes a single data point can tell the whole story, but not always—especially when dealing with metrics measured over time, like with battery-powered products.

Here’s an example. Headlamps often show a brightness measurement in lumens, and sometimes a battery life value (with a fully charged battery) in hours. It’s commonly assumed that the light will work at the listed brightness for the full battery life, or at least most of it. In reality, the tests for battery life and brightness are separate, and brightness dims as the battery drains. All lights have different arcs for how quickly brightness dims during use, but this information isn’t always clearly shared with consumers. It’s not that the specs on the packaging are false, exactly, but they’re not fully explained, leaving customers with an inaccurate impression or performance.

Marketing performance data without the full context is unfortunately common in the outdoor gear space, headlamps are just one example. Here at the Outside Lab, we’ve learned that we need to do our part to help make sense of these performance values and better explain the testing used to achieve them so that you can make a truly informed decision when buying gear. It’s important to note some brands do provide the full information on their packaging, so be sure you check.

Lesson: Not all marketed performance and measurement numbers are clear, so we need to help add context with gear tech explainers and testing.

Conclusion

We achieved a lot in the Outside Lab at CU Denver in 2025 through testing, research, and getting creative with our own protocols (like our rain shell abrasion durability test simulating 6 different scenarios). In the process we learned the need to clearly present test results, where we can add value with our unique capabilities, and how to think deeper about real-world use when testing. Our goal is to provide more complete reviews by adding objective lab data to our expert field-test reviews, helping you make the best choice in your next gear purchase.

We’re looking forward to another year of testing—and gear destruction—to learn even more about the products that get us outside. The more we test, the more you know.

What gear would you like to see the Outside Lab test in 2026? Let us know in the comments.