Map of Mao’s Long March, China

Trekking on the Trail of the Long Marchers

Trekking on the Trail of the Long MarchersChina

Horseman Jiu Jiu

Horseman Jiu JiuChina

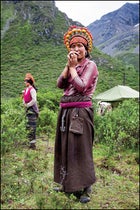

Local Tibetan hair dress on Dagushan

Local Tibetan hair dress on DagushanChina

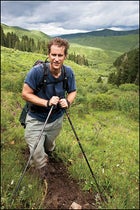

The author in the bog

The author in the bogDean King in China

Clockwise from top left: the horse caravan; Tibetan cowboy Gama; a local Tibetan woman; crossing into the grasslands; collecting beimu, Chinese medicine; a wolf skin; lunch on Dagushan; local sausage; a Buddhist monk

Clockwise from top left: the horse caravan; Tibetan cowboy Gama; a local Tibetan woman; crossing into the grasslands; collecting beimu, Chinese medicine; a wolf skin; lunch on Dagushan; local sausage; a Buddhist monkChina

A Tibetan tosses prayer cards for the wind to carry to heaven

A Tibetan tosses prayer cards for the wind to carry to heavenWE RECEIVED MIXED MESSAGES before setting off in Sichuan Dagu Glacier Park, a newly established preserve in Sichuan province’s Great Snowy Mountains. At roughly two-thirds the size of Texas, China’s fifth-largest administrative district has 87 million people (more than triple that state’s population). Still, its western border lies on the edge of the Tibetan Plateau, from which the Himalayas rise, hundreds of miles to the west. At an average elevation of 14,500 feet, the Snowies remain plenty wild: We were told bandits, mad dogs, and wolves roam the place.

To complicate things, the park lies in Heishui County, one of the hardest-hit by the Wenchuan Earthquake of May 12, 2008. Heishui, which is largely inhabited by Tibetan peoples and still heavily influenced by its lama monasteries, had been officially closed to all foreigners until 2004. The earthquake had temporarily shut its borders again, and no one knew the condition of the roads and trails.

Fortunately for us, our Beijing-based guide, Anglo-Aussie expat Ed Jocelyn, 41, and his Chinese partner, Yang Xiao, also 41 and a contributor to China’s edition of Outside, had recently opened Red Rock Trek and Expedition Company for adventures in western China. Ed, who has more Chinese miles under his boots than Marco Polo and had trespassed in this region in 2003, was sanguine about what lay ahead; he pointed above, where, he assured us, Tibetan lasses danced through pastures tending to their yaks, cooled by Dagu’s three 10,000-year-old glaciers.

It was early July, the beginning of the rainy season, and in the village of Xia Dagu, at 9,000 feet, the clouds hung on the firs like Spanish moss. Outside the quake-fissured stone house where we’d spent the night, Womudo, a hunched and blind Tibetan, gave us yet another warning: “The bodies of dead Long Marchers found on Dagushan,” he said, “were mauled by bears.”This piqued my interest most of all.

I’d organized the expedition to this remote region to clear up some of the mysteries surrounding the epic trek that had brought Mao Zedong to power in the Chinese Communist Party in 1934 35 and was afterwards turned into the nation-defining myth known as the Long March. Besieged in its Jiangxi-province stronghold in southeast China by the Western-backed Nationalist forces of Chiang Kai-shek, Mao’s overmatched Red First Army 86,000 men and 30 women had cut out on an October night in 1934 and simply vanished. Their plan was to regroup with other Communist forces (namely, the second and sixth army groups) 500 miles away in Hunan. But the Nationalists and allied warlord forces resisted fiercely and prevented that from happening. Instead, the First Army would march, fight, and suffer nonstop for an entire year in one of the longest and most brutal military marches in history.

Nine months and a staggering 3,000 miles after setting out, fewer than 20,000 battered First Army soldiers the rest lost to bullets, bombs, starvation, and exposure trudged into the Great Snowy Mountains. The women had served in many crucial ways on the march, from gathering food and recruiting new porters and soldiers to performing onstage for locals and troops and organizing stretcher teams to carry the sick and wounded. Three had been left behind two with wounded husbands, one to organize local militia and 27 remained. For the next two months, on the edge of the area known as “the Roof of the World,” the Reds dealt with debilitating altitudes, bitter internal strife (after merging forces with the Fourth Army), and deadly uncharted high-elevation bogs. They emerged and proceeded to march another thousand miles to northern Shaanxi province, where they established a new permanent base.

I’d come here to retrace one of the trail’s most harrowing stretches for a book I was writing on the 30 women and their fight for survival. In 2006, I had interviewed the last surviving female First Army veteran of the Long March, Wang Quanyuan, then 93, whose journey had taken a twist when she was captured by Muslim warlord Ma Bufang’s troops and forced to be a sex slave for two years before escaping.

Over the next ten days, guided by Ed and Xiao, their assistant Mike Tan, 40, and puckish Tibetan wrangler Jiacuo, 46, we intended to follow in Mao’s footsteps, ascending Dagushan on the highest pass of the Long March and crossing the zigzag continental divide (between the Yangtze and Yellow river basins) three times. A team of ten horses handled by four local Tibetan cowboys would carry our gear. We would switch teams in the Maoergai River Valley and cross the caodi, a stretch of high-altitude grassy bogs, where the Long Marchers had vanished by the dozens in inky pools that, as one Red Army soldier put it, “stank like horse piss.”

Traveling with me were several friends and colleagues: Andy Smith, a high-school history teacher and amateur nature photographer; college pal Lawrence Gray and avid hunter and fisherman Gordon Wallace, both businessmen on sabbatical; and Philipp Engelhorn, a Hong Kong based German photographer.

We would cover about 90 miles in all, almost always above 10,000 feet, in a place rarely visited by Westerners. That is, if we could actually get there.

IN THE EIGHTH century, the Chinese poet Li Bai famously proclaimed that it was “more difficult to go to Sichuan than to get into heaven.” Our arrival there had been delayed by 14 months, due to the magnitude-7.9 Wenchuan Earthquake, which devastated the region, taking some 90,000 lives, leaving millions homeless, and burying mountain roads. Finally, in early July 2009, I had made it to Chengdu, Sichuan’s robust capital.

Now two more obstacles had materialized. The 60th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China the Communist-led nation that arose after the revolution was won in 1949 was about to be celebrated, and the government had begun to crack down on travel @#95;box photo=image_2 alt=image_2_alt@#95;boxin and around Tibet to avoid any embarrassing political incidents. Meanwhile, a protest by the Turkic-Muslim Uighurs in Xinjiang province, a thousand miles to the north, had turned violent; at least 197 people had been killed and 1,600 wounded. Security officials went on red alert, checking IDs at road stops and clamping down borders.

Luckily, Ed, a Mandarin-speaking Russian-studies expert who swapped Russia for China more than a decade ago, is more than just a little savvy. Having walked the entire 4,000-mile Long March route with his friend Andy McEwen in 2002 03, and explored many of the horse and spice trails of western China since, he had picked up a trick or two.

The day we landed in Chengdu, he arranged for a press conference with Sichuan’s largest newspaper. A headline the next morning dubbed us “the Seven Friendly Foreigners.” On our grueling three-day backcountry drive through the Snowies to reach Dagushan, Ed had wielded the article like a badge at checkpoints. At a forestry outpost at the foot of Jiajinshan, the deadliest mountain on the Long March, our van was stopped by uniformed officers and we were told that the road had been closed for three months. Ed presented his papers with the article on top, and an exception was made. Not only were we allowed to pass; we ate lunch in the foresters’ mess before setting out. Bulldozers cleared the road of dirt and debris ahead of us as we drove.

Sichuan Dagu Glacier Park was not yet open to the public when we arrived, though it already had an impressive new Soviet Bloc style lodge and 40 brand-new buses in a mall-size parking lot ready to haul visitors up to see the glaciers. In pursuit of the high pass over Dagushan, we left the village of Xia Dagu on foot and headed up through a jungle-covered gorge of ferns, firs, and at times knee-deep, boot-sucking mud. This working yak herders’ trail climbed a ridge with several hair-raising downhill drops, and twice we had to turn sideways to make room as caravans of horses loaded with yak butter passed. Not far away lay a dead cow stiff but untouched by bears.

We reached the summer pasture at 13,000 feet around happy hour. Sure enough, the meadows were full of yaks, dhoykes the vicious Tibetan mastiff dogs famed in the region and lovely untended yak tenders. One lass with creamy skin and quarter-moon eyes fearlessly invited us into her cabin. Squatting beneath yak jerky hanging from rafters, we sat around the woodstove as she dished out sweet bowls of yak-milk tea.

“There’s a sense of freedom in the people,” Ed said. “You don’t see many fences here, and you also don’t get any sense of indulging in poverty tourism’. The Tibetan herders might not have much cash money, but they have a spirited and strong culture and look outsiders in the eye as absolute equals.”

In fact, in these Tibetan lands, the Red Army had to contend with a fierce people. Advised by their lama monk leaders, who had been doing battle with outsiders for centuries, the Tibetans melted into the mountains before the Reds’ arrival, only to return and pepper them with sniper fire, cut the throats of stragglers, and push boulders down on the marching columns from above.Our second night on Dagushan, we pitched camp at 11,500 feet just before a colossal downpour and lightning storm emphasized the failings of our tarp, where we cooked and ate, and where some of us slept. Nevertheless, Ed fired up the gas stove and whipped up a feast of rice with pumpkin and sausage made by Xiao’s family. For the fearless, Ed like Mao, a fan of culinary heat added a dish of cabbage, bacon slabs, and mouth-numbing black Sichuan peppers.

As the others turned in, Ed and I continued our ongoing conversations about the Long March. He and Andy McEwen had written a book on their journey, in which they detail such groundbreaking discoveries as finding a woman who was potentially Mao’s lost daughter, born to He Zizhen, his wife at the time, and abandoned on the trail.

After retracing the First Army route with Andy, Ed had walked the entire, even longer, route of the Second Army (which had eventually met up with Mao) with Xiao, who is equally passionate about the Long March. Ed has visited every survivor who would see him and now has a better grasp of the Long March than any other Westerner.

“You’ve got to write the definitive Long March account,” I told him.

“I don’t know,” he said with a sardonic chuckle. After returning from each of his expeditions, sitting in front of a computer in his small Beijing apartment, Ed confided, he’d had “crushing depressions.” He prefers above all to be in the field.

It had taken us a day and a half to reach the top of Dagushan. By then we had discovered why Mao and his gang had suffered so terribly. Even in summer, the winds were icy up top and the air thin. In straw sandals and cotton shirts, the 27 women, by then with shaved heads to rid them of lice, suffered from exposure and altitude sickness. After terrible cramps in the Snowies, Wang Quanyuan, then 22, would later find that she’d developed permanent infertility here.

By the time we approached the pass, at 14,661 feet, we were at the highest point of Mao’s Long March. None of the women, who were preoccupied with surviving, ever mentioned in interviews the stark, magnificent view of distant peaks, glaciers, and waterfalls that we now scanned.

IN ALMOST EVERY VILLAGE, we saw signs of damage from the Wenchuan Earthquake, which made buildings sway as far away as Shanghai, more than a thousand miles to the east. In the village of Hadapu, the place where the Red Army finally reemerged from the Tibetan region of China kissing the ground as they did we would see the worst destruction. Whole sections of old houses, shops, and temples were reduced to rubble. Cement facsimiles were now rising in their places.

Xue Luo, a village at the bottom of Dagushan, typifies the double-edged sword of progress in these parts. Here on a small tributary of the Maoergai, the Chinese government has begun building a new village of identical stone houses with red roofs. One cannot dispute the step up in comfort. The atmospheric old village of intricately carved wooden houses sits just above it, doomed to oblivion.

In the village of Wodeng, a local handed us a note, which read that the two-story mud-and-wattle house in front of us was the site of the watershed Shawo Meeting. Ed and I looked at each other. This was a startling revelation. A young guy named Yixi, whose father was away herding in the mountains, let us in. As was typical in a traditional Tibetan house, livestock lived on the ground floor and the family above. We climbed steep wooden stairs. Yixi pointed out the view from the front window of a large sandbar in the stream. It had always been assumed by Westerners that the famous meeting, at one of the most politically sensitive stages of the Long March, was so named because it took place in a village called Shawo. But now Yixi explained that the words sha wo can be translated as “house by the sand”; the Reds had looked out the window and called the gathering the Sand House Meeting. We’d added a footnote to history.

Here, General Zhang Guotao, leader of the Red Fourth Army, which had met up with the First Army in the Snowies, wrangled with Mao over the structure and leadership of a unified force. Zhang commanded a far larger, better-equipped, and less battered army. But Mao controlled the Communist Party leadership and was more clever in every way. At Shawo, they combined and redivided the troops in an arrangement that appeared favorable to Zhang, but actually kept Mao on his path to ultimate power.

Outside, oblivious to this transcendent moment, a crowd had gathered to watch Gordon assemble his fishing rod. On his first cast, he landed a footlong Chinese cousin of the catfish, then released it. Strictly speaking, Tibetans, being Buddhist, don’t eat fish.

At a nearby village where we stayed overnight, Ed and Xiao were lectured by a drunk police chief, who, toeing some old party line and mixing his politics, harangued them for more than an hour: “You people from capitalist countries must understand this is a socialist country, and you must respect our different rules! We are Tibetan, we will never go back to the time of feudalism!”

But the hospitable Buddhist monks of the valley’s lamasery, which included a two-story white-painted temple and homes for several hundred holy men, had no qualms about the visiting Westerners. They welcomed us warmly, showed us around their temple, and introduced us to the tonsured nuns at a nunnery nearby. They also served us tsampa, the staple of the Tibetan diet. The Long Marchers, from rice-eating Han China, had a hard time digesting this paste of barley, yak butter, yak curds, and tea. We soon felt their pain.

THE SOUTHERN END of the Snowies is dominated by Mount Gongga, the 24,790-foot peak immortalized in Men Against the Clouds, the classic account of an American team’s successful attempt in 1932 to become the first to summit Sichuan’s tallest mountain. It’s also the site of many climbing accidents, including the May 2009 avalanche deaths of Colorado climbers Micah Dash, 32, and Jonny Copp, 35, and 24-year-old Minnesota filmmaker Wade Johnson. In 1935, the Red Army wisely skirted the treacherous behemoth, but they could not avoid another nightmare, one that awaited them just north of the range.

The most demoralizing stretch of the Long March lay in the uncharted caodi, a system of ridges and bogs, which the Red soldiers called mofengyu a disparaging term for a person with a pockmarked face. Here, the Reds faced wind-driven rain, sleet, and hail. Hundreds died of hunger, exposure, and exhaustion, many drowning in pools of mud and rotting grasses that absorbed them like quicksand.

Now, as we were about to enter the caodi with ten fresh horses and a new set of wranglers, their leader, Sanjindao, 41, neat and inscrutable in a fedora, told us they could not go up the first valley. Their village had a blood feud with villagers in that valley over the right to harvest aweto, a valuable medicinal fungus that grows on caterpillars and is used in the local moonshine. Eight people had been killed in the fighting. So we had to detour several miles to the next valley. There wasn’t anything we could do at this point but add the extra miles to our route.

Crossing a ridge at 12,000 feet, we could sense that we had entered a wilder, emptier place. So large a party does not pass unnoticed in this area, and the Tibetan wranglers feared a raid from their rivals, the same people who’d made the Red Army’s passage here so miserable. At dusk, we circled up the tents on a shelf above the bog and kept the horses inside the ring. With no trees on the hills, the Tibetans hacked up boards they had carried with them and built a fire in their vented tent. Philipp, Lawrence, and Andy crawled inside to join them and warm up. Communicating in sign language and grins, the Tibetans brewed tea and passed around a Sprite bottle full of white lightning.

Green mosquitoes swarmed us, which to Gordon meant a fresh hatch to try on one of the many rivers. He crawled through the fences of an empty winter compound to reach the river but only met heartache.

The rain came down again that night as we huddled around the lantern under the tarp. Jiacuo, who had a sun-scorched shaved head, told stories in Tibetan, which Mike translated into Chinese, Ed turned into Anglo-Aussie English, and Lawrence and Andy sometimes re-dialected for the Americans. The Tibetans called the Red Army the “Eat Everything Army,” according to Jiacuo, who lives in the village of Cirina, which the Red Army eventually occupied and we would visit. We later discovered, to our surprise, that Jiacuo, who cheerfully performed some of the camp’s lowliest tasks, like digging the latrines (always with a view), is a Communist Party member and lives in a large home whose pine-paneled living-room walls are hung with salt-cured pigs halved down the middle from head to tail.

“They killed all the soldiers left behind,” he admitted of his village ancestors, “except for the children.” The Red Army called the youths that traveled with them “little devils.” In Cirina, a 12-year-old covered in sores had shown up at the doorstep of one family. They shooed him away. He showed up the next day, and they shooed him away again. On the third day, when the boy returned, the family decided it must be fate and kept him. His children still live in the village.

Now that he’d warmed up, Jiacuo, whose devilish grin made him a camp favorite, told us a ribald tale about Ma Bufang, the leader of a clan of Chinese Islamic horsemen whom the Red Army soon fought. “Ma Bufang kept a harem of 20 women,” he said. “He made them keep dates in their vaginas for two days at a time. He would then eat the dates to give him virility and longevity.”

ED’S NEXT EXPEDITION will be over one of the tallest of the Snowies crossed by the Fourth Army, 17,950-foot Danglingshan. “The peak is clearly the highest,” he said, “but there’s no record I can find of anyone crossing it in modern times.”

Fast running out of Long March peaks to bag, Ed has another obsession: the tea trails into Tibet. While the main routes, which crossed Sichuan, are now mostly paved roads, he has set out to find and chart the north south spurs that connected adjacent districts to the main lines. “The minor trails are the exciting ones,” he said. “They reach into remote parts of areas the size of U.S. states that are basically virgin territory for trekking.” Once he documents these trails on treks that adventurers can join via his Red Rock trekking company he hopes it’s possible to link them in a continuous network, “something like a Chinese version of the Appalachian Trail.”

Deep into the grassland bogs, a week into our trek, it rained torrentially, saturating the endless convolution of ridges, bogs, and streams trilling off in all directions. Picking his way from grass clod to grass clod with his camera gear strapped to his chest, Andy finally splashed down in a murky pool. “The clods got smaller and smaller,” he explained, grinning, “until it was check and checkmate.”

Under such conditions, the female Long Marchers often had to sit upright, back to back, to sleep. “The food ran out, and we had no salt. People felt weak all the time,” a woman called Little Sparrow, then 29, later said. “The swamp was dangerous, and many people sank in and never came back.”

The driving rain took us with such ferocity that, despite the gaiters we wore, our boots filled to the brim. Cold and drenched, we reached Galitai, a nowhere highway stop, and filed into the Grasslands Diner, a metal shack with a pipe chimney billowing black smoke. We’d cross this highway and head north, still through desolate caodi, on an old tea-trail route to Tibet for the last 30 miles.

Inside the diner, with our gear hanging from the rafters, we filled glasses with moonshine from a pickle jar on the counter and exchanged toasts with our wranglers. This wasn’t just any moonshine. It was a regional specialty, and medicinal stuff sorghum liquor with deer antler, aweto (caterpillar fungus), beimu (medicinal grass roots), hongjintian (an herbal concoction used for altitude sickness), ginseng-like dangshen, and dates.

The place began to feel cozy, until the outside door swung open in a western-saloon moment worthy of Sam Peckinpah. Three long-haired biker bandits in yak-hide tunics stood in the doorway. Our horse crew, suspecting they were from the enemy village, froze. The baddest badass, with a gold tooth and a yard of blade in a gold scabbard hanging from his belt, scanned the joint. Twenty-eight petrified eyes stared back at him. Not a word was spoken. Apparently he did not like his odds. (Up against the Seven Friendly Foreigners, who would?) The door slammed shut again and the bikes zoomed off.

NORTH OF THE HIGHWAY, we made gratefully for the even more remote Baozuo Valley. “It’s hard finding places where man hasn’t shaped the land,” said Ed as we scanned the empty valley below.Over the next two days, we would walk beside the Baozuo River on the ghost of a Qing Dynasty road, part of one of the remote tea trails that Ed now waxes on about.

“These trails are a direct connection to the old days of great caravans journeying for many months,” Ed said, “the kinds of journeys I read about in adventure books when I was a teenager.”On the second day out, atop a steep ridge at 13,100 feet, we gazed up the Baozuo Valley, toward the exit from the caodi, where the Red Army had fought the Nationalists and escaped their liquid nightmare. Our horses were edgy, perhaps spooked by the wildlife or by the shifting clouds. One bucked, chucked its load, and made a dash for it, and two more followed. Sanjindao and Gama, his second in command, leaped on two others and chased down the runaways. A late-afternoon storm drove us into the dung huts of a winter camp by a river. As the light faded, shadowy animals barked at us from the steep hillside, and two large unidentified beasts with long red tails, white manes, and charcoal fur prowled. Our horses bunched, pacing and whinnying.

Gordon remained unspooked, however, and returned from the river with a grin and a sizable fish that Mike ID’d as a highland scaleless carp. The Tibetans didn’t mind if we ate it. Pan-fried, it was delicious.

A six-hour, 15-mile trek through the upper Baozuo Valley the next day would take us to the Reds’ exit point from the caodi. Under far different circumstances, we would celebrate the end of our trek. Beyond the reach of officialdom, we’d found a rugged wilderness deep inside China, with few people and vast, wild expanses. “This isn’t a place for day trips and so should escape the mass tourism that weighs on parts of Yunnan,” Ed said.

Organized efforts to try and link trails be they Long March or tea trails are still years away, says Ed, who, despite the complications inherent to China, remains hopeful. “The first step is to establish the concept and to encourage responsible use of these resources.”

The second step? Well, for Ed and Xiao, it will be in a remote valley or on a high slope. If they have their way, this part of northwest Sichuan will become one of the world’s next great adventure destinations.