THOU SHALL NOT look the talent in the eye.

the star plays with his food

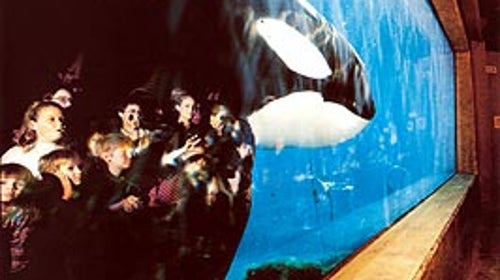

the star plays with his food Foster inspects a satellite tag on Keiko’s dorsal fin

Foster inspects a satellite tag on Keiko’s dorsal fin

Thou shalt not pat, stroke, rub the nose of, or otherwise fondle the talent.

Thou shalt neither encourage the talent to ham it up nor applaud his antics, no matter how much he begs for attention.

These are the commandments one must abide by to land an interview with the world’s largest movie star–more reclusive than the retired Garbo and undergoing a tough-love rehab program in a remote corner of Iceland. Having sworn not to molest him, I’m escorted onto an eye-popping neon-orange skiff called the Draupnir, which will ferry his entourage and me across the harbor of Heimaey Island, off the south coast of Iceland, to see the celebrity shut-in.

“Nobody from the media has been allowed to see him for, I’d say, at least a year,” his main handler, Jeff Foster, yells to me as we rocket over wind-whipped chop. “ABC, NBC, and other TV crews came out, but they could only shoot him from across the bay. No close-ups. Were they pissed off…” For the first time in seven months, he explains, the star will be taken for a “walk,” the start of an exercise program to shape the couch potato up for summer.

“You don’t have a camera, do you?” Foster interjects, panicking suddenly that he forgot the fourth and most vital commandment: Thou shalt not photograph the talent. “No? Good. Because he performs for the camera, and we’re trying to get him away from that. He learned to love the camera during filming. Remember not to look straight at him. Only take a peek indirectly out of the corner of your eye.”

Foster, 45, is a lifelong sea-hound from Seattle with an earthen all-weather tan and a shaggy mop of thick dirty-blond hair. In his time he has served some major divas, including a 1,700-pound walrus named Georgie Girl who for months used to plop her head in his lap every evening and moan contentedly while he read her bedtime stories. Many aquarium veterans consider Foster the world’s top marine- mammal tamer, a man with an innate gift for charming sea creatures. He routinely gets into tanks with his outsize heavyweight charges, roughhousing with them as though he were one of them. Normally he’s a laid-back, roll-with-the-punches guy, but today Foster is edgy; he has to ensure an interloper doesn’t goose the talent’s ample flank or play paparazzo.

“You never get used to spotting him for the first time,” Foster relates as the boat slows and pulls into a cove. “Every time you see him, you get a little thrill. Some people get out of control.”

I practice averting my gaze, but before I’m fully prepared, the 10,000-pound star sneaks up on us and exhales loudly. He tilts his head and it’s clear he’s angling for an introduction. For my part, I instantly break the solemn commandments I swore to uphold only minutes ago and make eye contact. It’s too hard not to react, not to flirt with the headliner in his white collar and black tuxedo, shiny as a Kalamata olive. More loyal than Lassie, brainier than Barney, friendlier than Flipper, swift as Secretariat, bigger even than Big Bird and Dumbo–Keiko the killer whale exudes the kind of instant allure that makes it clear why he’s become an idol.

LIKE EVERYONE else, I heard of Keiko’s legendary charm from some of the thousands of print and television pieces that cheer-led the Free Willy movement. Caught in 1978 or 1979 off the south coast of Iceland by an American team that collected orcas for the marine-mammal trade, the two- or three-year-old killer whale atrophied for a year in an aquarium pool near Reykjavík, where he had been stashed because, rumor had it, his capture exceeded the number permitted that year. (Because of poor record keeping, it’s difficult to confirm when, exactly, he was caught.) Then he shipped out to Marineland of Canada, where run-ins with an aggressive male orca made for an unhappy home. From there, he got exiled to the boondocks–a cramped, smog-ridden amusement park called Reino Aventura in Mexico City that gave him top billing, but also skin lesions–caused by the whale equivalent of papillomavirus.

Keiko’s big break came in the early 1990s when SeaWorld–which owns most of the 52 killer whales in captivity–rebuffed the casting call for orcas to star in the Warner Bros. flick Free Willy, the story of a troubled teenager’s struggle to liberate an oceanarium’s trophy whale and reunite him with his family. Apparently, unlike the SeaWorld execs, Keiko’s Mexican owners hadn’t read the screenplay. They signed the ailing, severely underweight Keiko up for the role, unprepared for the 1993 film’s smash success and the real-life fight it would trigger between animal-rights activists and the marine-park lobby over liberating the movie’s star. The hot property then went on tour. First, in 1995, he was donated to the Free Willy Keiko Foundation, and upgraded to four-star accommodation at the Oregon Coast Aquarium in Newport; later, in 1998, after a lengthy lawsuit (the Oregon Coast Aquarium sued to keep Keiko, arguing he was too ill to fly), he was flown in a fiberglass tank aboard a U.S. Air Force C-17 cargo jet to the North Atlantic waters whence he came; in 1999, the Free Willy Keiko Foundation merged with the Jean-Michel Cousteau Institute (run by the son of Jacques) to form Ocean Futures, a nonprofit with 18,500 members, based in Santa Barbara. Today, a retinue of 16 foreigners and 13 locals works round the clock to keep Keiko happy and to reintroduce him to the wild.

His emancipation isn’t coming cheap–$3 million per year–but seeing his charms in the flesh, I understood how the cult of Keiko had grown to more than 1.2 million, mainly children, who made phone calls or wrote letters and donated their dollars and pennies to the cause. VIP devotees include Jimmy Buffett (who sent in $500), Michael Jackson (who offered him a home at Neverland), and telecommunications billionaire Craig McCaw, whose namesake foundation has put up most of the project’s spending money.

Orcas are not an endangered species, and Keiko’s keepers say they have no agenda beyond freeing the celebrity–as soon as this August if Keiko will go. It’s not a science experiment or a potential model for busting other orcas out of their tanks; it is, insists Charles Vinick, executive vice-president of Ocean Futures, a simple act of humanitarianism for a beloved whale.

“This would never have happened if Keiko wasn’t a movie star,” he says. “The movie brought this whale into the hearts of millions of children who were able to give conscience to a movement about what we as humans can do to protect the environment. This is not about what could happen to other captive animals. We’re talking about this one whale.”

When I starting looking into it, I loved the idea that whales–or one whale–could go home again. The story line reminded me of Born Free, the tale of Elsa, the tame lion who returned to the veld and went on to raise her own wild cubs. Yet what finally got me to Heimaey Island was not the life-imitates-art scenario, but the rumors that the project wasn’t working out. By all accounts, Keiko didn’t want to go native. Five years and approximately $20 million later, even the optimists admit that chances are slim for tame Keiko to swim off with his wild brethren this summer. For one thing, there isn’t much time. Keiko is in the autumn of his years. Male orcas in captivity tend to live 20 years or less; in the wild, up to 45 years. Keiko is at least 25.

“Keiko is already living on extremely borrowed time, past the age when most males in captivity have lived,” says Erich Hoyt, author of the orca ur-text Orca: The Whale Called Killer and a senior research consultant for the Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society, a UK-based charity with 70,000 members. “They have only themselves to blame. They have stalled and stalled. Every day and week and month that goes by makes success less likely.”

Other pessimistic observers are second-guessing the whole program. There’s even a conspiracy theory circulating that the Keiko freedom ride has been designed to fail, so that kids won’t clamor for more show whales to be let go. I don’t take this seriously, but it is a bit strange that everyone involved in Keiko’s rehab is an expert in training captive orcas and that they are relying on tried-and-true taming methods to “condition” him for the wild. Hiring specialists in animal subjugation to undomesticate what is essentially a house pet sounds about as logical as enlisting R. J. Reynolds execs to run Smokenders. In a further irony, Foster, Keiko’s chief warden, suspects he may have been one of the animal’s original captors; in the 1970s, his father-in-law, a pioneer of whale-catching, sent Foster here to collect orcas.

And don’t even get the locals started. Iceland ceased commercial whaling operations in 1989, and former whalers remain bitter that their well-being comes second to that of a washed-up show-biz cetacean. They even have their own conspiracy theory: that Keiko is a Trojan Whale sneaked into Iceland by Greenpeace to ensure that the country that welcomed its lost orphan back home can’t turn its new eco-friendly image upside down by reintroducing whaling. Other Icelanders, disillusioned by the hype that had promised the now off-limits Keiko as a million-dollar tourist magnet, see the whale as proof that Americans have nothing better to do than extend human rights to fish. For cartoonists, stand-up comedians, and amateur jesters on the mainland, Keiko’s the national joke.

“Female whales have swum by him, but when Keiko gets horny, he humps the tires strung along his bay pen instead,” Iceland’s top chef, Siggi Hall, teases me one night in his restaurant in downtown Reykjavík when he learns that I have a date with the infamous whale. “His trainers have taken him out to swim, but he always comes home like a good little puppy. This isn’t a killer whale, it’s a pet mammal. We could get better use out of him on the dinner table! Do you know how many whale steaks I could get out of him? But Keiko’s so old, he’d be hard to cook and tough to eat,” Hall continues. “We could boil his blubber down. Imagine how many soap bars and Keiko candles we could make out of him!”

HEIMAEY HARBOR IS, as Herman Melville once wrote, “cold as Iceland.” With its vertiginous cliff faces and petrified volcano cones, Heimaey offers one of the most wildly beautiful landscapes in the country. But the tiny strip of land, dotted with two-story cottages roofed in a rainbow of Crayola colors, is also Iceland’s most treacherous. A volcanic eruption in 1973 buried half of the fishing village under 250 million square meters of molten lava and ash, forcing the whole town to evacuate and then return years later to rebuild. Rough seas around the island routinely sink cod and herring boats. And the island’s weather, where winds of up to 170 miles per hour are not unusual, is considered the worst in the island nation.

Whatever your take on the folks working to free Keiko, you can’t knock their dedication. The 16 international staffers rotate into this hurricane-prone freezer on seven-week assignments without a day off, starting early in the morning to prep the 140 pounds of fish that comprise Keiko’s food rewards and often ending more than 12 hours later. They’re a colorful bunch, too, that includes a group of former SeaWorld animal housebreakers; Steve Sinelli, a retired high-tech executive from Oregon; Smari Hardarsson, the 1998 Mister Iceland; and Keiko’s vet consultant, Lanny Cornell, the former SeaWorld chief zoologist who was fired after a series of bloody run-ins between humans and captive orcas. Cornell currently advises the Las Vegas Mirage casino on its pet dolphins and recently helped Marineland of Canada acquire new belugas from the Russian military.

“It’s not as easy as it looks,” says Sinelli, who signed on as a 50-day volunteer and ended up staying for three years. “My wife only gets me half of the year. I don’t think any of us expected to be here so long. It does get lonely. But the payoff is in trying to accomplish something that everyone says can’t be done. Regardless of the outcome, I don’t feel there’s any failure.”

If it isn’t all smooth sailing for his entourage, so far Heimaey has been good to Keiko. He’s in the most natural environment since his capture. Instead of being restricted to a man-made tank, Keiko’s confined to a bay the aggregate size of 20 soccer fields. Instead of watching action videos and groups of children through aquarium glass, he can observe schools of fish that swim through his pen, along with the gulls and puffins that swoop down from the cliffs overhead. He’s no longer part of an hourly dolphin show presented on hot summer days before audiences of hundreds of screaming and applauding fans. No wonder, even though he’s probably still a virgin, he seems in no hurry to leave his halfway house.

On the other hand, some basic facts of his captive routine remain the same: Humans plan and run his daily regimen. Using the fish-reward method employed by theme parks to train marine mammals, their protocol is to tutor the tame animal in wild orca practices in the hope that he’ll eventually pass for a feral whale. So Keiko is still singing for his supper, only the show tricks– behaviors,” in the performing-orca biz–have been rebranded “aerobics.” Foster tells me that the team works the whale out with “18 to 35 exercise sessions a day in winter, up to 50 sessions per day as the days get longer,” with the goal of making him fit enough to keep up with wild whales.

Out on the Draupnir for Keiko’s walk, Brian O’Neil, a hunky thirtysomething redhead who first worked with Keiko at the Oregon Coast Aquarium, unhinges a plastic mesh platform off the side of the boat and crouches down on it, signaling the orca to come alongside and follow the craft as it kicks into higher gear. O’Neil points the yellow Styrofoam end of a black target pole above the point in the water where he wants Keiko’s head. With the target pole, he commands the whale to swim parallel to the boat; then he indicates for him to hang out astern, in the motor’s foamy wake. The idea is to encourage Keiko to approach the pace and endurance levels of wild whales, which swim in short bursts of up to about 35 miles per hour but usually cruise more slowly, covering up to 100 miles per day. As we circle the bay, the Draupnir is going 13 miles per hour.

“Think of the bay as a track and us as coaches and him as an athlete we are training for a marathon,” Foster says. “Only the marathon is the open ocean.”

In Keiko, Foster may see a marathoner in training, but the picture I get is of a five-ton cocker spaniel going to obedience school. The Moby Dog impression is strengthened by O’Neil, who after every correct response rewards Keiko either by grabbing herring from a shiny stainless-steel bucket and flinging them into the bay or by tooting a silver dog whistle, called a bridge, as a secondary reinforcement. “The bridge is instant confirmation,” O’Neil says. “Keiko knows it means ‘good job, good boy.'” So much for curtailing the whale’s need to please people.

“ONCE A TRAINER, always a trainer. All the wrong people are involved in this. They’re still doing obedience training, using that whistle,” rails Richard O’Barry, founder of the Dolphin Project, a Florida-based group dedicated to freeing captive marine mammals, as well as a consultant for the World Society for the Protection of Animals, an animal-rights network with 380 member organizations in 80 countries. “At least Keiko is back in home waters, experiencing the natural sounds of the sea and the rhythms of the tide. But he’s still being exploited. The whole plan to ‘train’ Keiko to be wild is ridiculous, a captive idea, and the main problem. They’re putting on a whale rehabilitation show, not letting the whale go wild.”

Captivity mavens consider O’Barry an extremist. On Earth Day 1970, he was arrested for stealing a dolphin and and trying to free it. On other occasions, however, he’s been more successful. Sure, a few of the dolphins he’s freed have had to be recaptured because they swam into shallow inlets to beg humans for food, but others joined up with wild dolphins, never to be seen again. O’Barry is also a former dolphin tamer who makes no bones about his résumé. He trained the dolphins who performed in the 1960s TV show Flipper and became a marine freedom-fighter after one of his trainees died in his arms at the Miami Seaquarium.

O’Barry has an alternative model for freeing Keiko. “First of all, you get rid of all the trainers, anyone connected to the captivity industry whose history with animals involves obedience. Then you back off and let nature take its course. You try to become invisible. To diminish human contact, first you wear sunglasses, so they can’t see your eyes. Then you wean them off anything connected to captivity–buildings, boats, buckets, man-made objects, training behaviors. You stop asking them to do anything. You feed them live fish at random intervals for doing nothing, not for doing something. And you build a blind, and you throw food from behind it to sever the dolphins’ connection of food with humans.

“You stop feeding them bits of dead fish. First you feed them dead fish halves, then whole dead fish, then partially alive fish that have been stunned, then live fish,” he continues. “Then, if you want to make them wild, you stop feeding them, period. When they can hunt fish for themselves, you can set them free.”

Ocean Futures PR material touts the fact that Keiko is “continuing to increase and approximate natural feeding patterns” and now gets “up to 50 percent of his food in the water column.” I assumed this means he now forages for half of his food. I am wrong.

“Actually, it’s now closer to 100 percent from the water column, which means that we don’t feed him by hand directly into his mouth anymore. We throw fish into the water for him to retrieve,” says Charles Vinick. Translation: Humans supply Keiko with 100 percent of his diet, between 90 and 140 pounds per day of dead herring. Vinick contends that 25 percent of the food the team feed him is live fish, but on the day I visit Keiko in Heimaey, all the food he gets is formerly frozen.

“We don’t feed him live fish every day. Maybe every week,” Foster says. As for Keiko chasing down the live pelagic creatures that swim continually in front of his nose, Foster is doubtful. “We’ve never seen him eat live fish, so we can’t speculate. We have seen him chase cod and pin it down with his nose, but that might just be cat-and-mouse play behavior. My gut feeling is that he’s probably never been food-motivated enough to forage. But we’re not concentrated on getting him to hunt. Our main goal is conditioning,” he says.

But if Keiko is to be self-sufficient and to not haunt fishing boats begging for scraps, won’t he have to hunt for himself?

Because orcas hunt in packs, Ocean Futures argues that Keiko won’t go for his own food until he’s fully free and accepted into a group of wild whales. “We can’t teach him navigational skills, where food sources are, or how to catch them. The best thing for him to do would be to integrate into a group of wild animals and let them teach him all that,” Foster avers, reminding me that tame animals, such as stray house cats, revert to hunting instinctively when they’re hungry.

Unconvinced, I call Kenneth Balcomb, founder of the Center for Whale Research in Friday Harbor, Washington, a 60-year-old research biologist who has studied the population dynamics of wild orca pods in the North Pacific for the last 25 years. He thinks Keiko could learn to feed himself before he’s free.

“Hundreds of whales come to the waters off Heimaey every year because of the herring spawning grounds there. All you’d have to do is take Keiko over to where wild whales are traumatizing fish schools and eating them,” Balcomb suggests. “If Keiko were hungry at that point and not magnetized by a metal fish bucket, he’d see all his buddies out there eating live fish and he might join them. It would be a good opportunity for him to learn how to hunt.”

SINCE ORCAS STAY with their families for the bulk of their lives, Keiko’s best chance of a successful return to the wild might be to hook up with his kin. That’s what happens in Free Willy 2, anyway, in which our hero rejoins the Pacific family pod that scientists have dubbed “J.” I figure flesh-and-bones Keiko is entitled to the same prodigal-son welcome home that celluloid Willy got. But the helicopter and several boats now looking for wild playmates for Keiko in the North Atlantic aren’t focused on a family reunion.

“We’ve never set finding Keiko’s family as a research goal. We’ve taken 11 genetic samples and dozens of photo IDs of killer whales, and we’re looking for similarities,” says Vinick. “But to go to the level of specificity of finding his family would be very difficult. You’d need a huge team and more resources, and our team is dedicated to Keiko.”

Actually, according to wild-whale specialists, locating Keiko’s family pod would be easy and cost-effective, and would dramatically increase the chances of the orca’s permanent return to nature. After the $7.3 million cost of Keiko’s digs at the Oregon Coast Aquarium and the $1.3 million move to Iceland and the 35 months the whale has spent in his pen in Heimaey, finding his family looks relatively quick and cheap. Balcomb, director of the Center for Whale Research and pioneer observer of “J” pod, estimates that it would take four grad students on stipends 30 days during herring season to locate Keiko’s sibs.

“I’m confident we could find his family. The whale population around Heimaey is 600 whales. I’ve cataloged 30 whales in Iceland in one night. You could identify the entire whale population in one herring season and find Keiko’s family pod,” Balcomb postulates. “He might not recognize his own family, but his mom might look at him and wonder. There would be some kind of connection. We’ve seen it with other large mammals, like elephants that have been returned to the wild and to their families after having been snatched away as infants.”

In many ways, this summer is Keiko’s last best chance to make it back to nature. At the end of March, the town’s mayor signed a deal with a Norwegian salmon farm to take over Keiko’s bay next year, and Icelandic officials say the whale will have to move this fall. Vinick acknowledges that the group is looking for new homes for Keiko in case he’s not free by September. They are committed to caring for the orca for the rest of his life.

Meanwhile, as per an Icelandic government-approved plan, Keiko is sporting a tracking-device on his dorsal fin. If he’s within 20 miles of the control boat, a VHF transmitter allows a boat to follow him and close in on his exact location in real time. If he surfaces, a polar orbiting satellite records his location so his complete path can be charted later. The ostensible reason for the tag is to monitor Keiko’s condition and whereabouts and, should he go free, to allow for intervention if he gets into trouble. Which is to say, it enables further human meddling.

“Ideally, we want him to be tagged forever, because he’s become an ambassador of his species,” Vinick notes. “He can tell us more about the wild whales he’s with.” Foster goes further. “If we reintroduce Keiko to the wild, there’s every possibility with the satellite tag that we can relocate him and, even after he’s integrated into a pod of animals, recall him back to the boat. We’ll be able to attach suction cups and new monitoring devices to him, maybe even a camera pack that sends images back to us.” Funny, but the Oxford English Dictionary entry for “freedom,” which includes the words “autonomy” and “emancipation,” makes no mention of ongoing obeisance to former masters. Ocean Futures wants to have it both ways–to succeed in freeing Keiko, but to be able to call him home, too.

I confront Vinick with the conspiracy theory that a cabal of marine-park owners lurks behind the scenes, making sure Keiko doesn’t go free. He fails to see the humor and issues a categorical denial.

“It may look slow, but three years is a human schedule, not a Keiko schedule,” Vinick stresses. “We’re learning how easy it is to capture a whale and how difficult it is to put one back.”

Difficult, but not impossible. Although Keiko is the first aquarium whale to be purposely reconditioned for the wild, a handful of other confined whales have escaped their captors and made it back to the ocean–to stay. Back in 1971, the U.S. Navy was teaching two orcas it caught in 1968, named Ishmael and Ahab, to retrieve missile debris from the sea floor. Just like Keiko’s trainers, Navy animal behaviorists schooled the whales to follow a lead boat from their coastal pens into the open ocean and to return to the boat at an audio signal. One day, Ahab took a 50 kilometer joy swim, but was recaptured. On another day, Ishmael spotted a whale pod in the distance and, ignoring the insistent siren call of the herring bucket, swam off. He never returned to base.