Joel Edgerton Talks 'Train Dreams,' Nature, and Finding Peace in the Wild

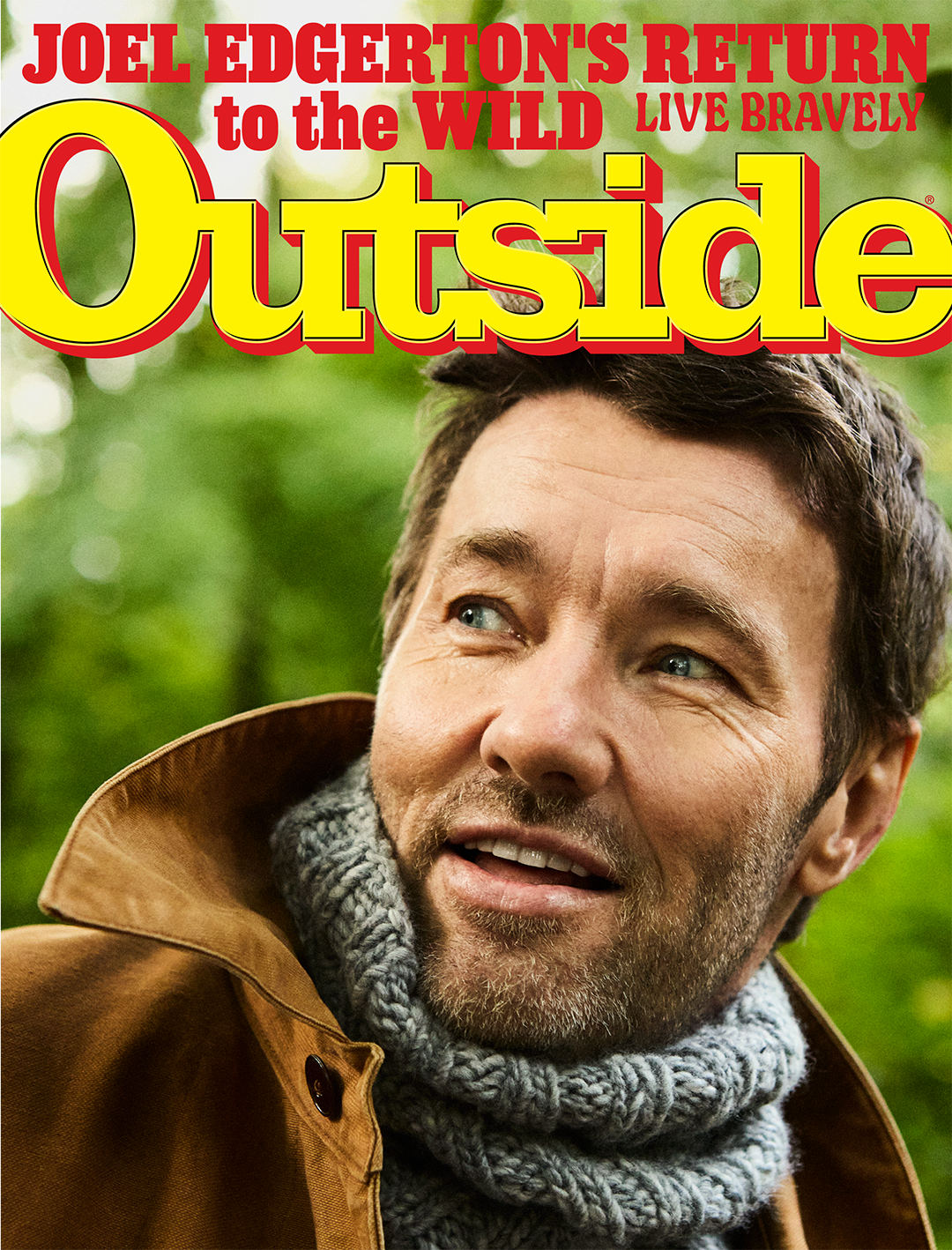

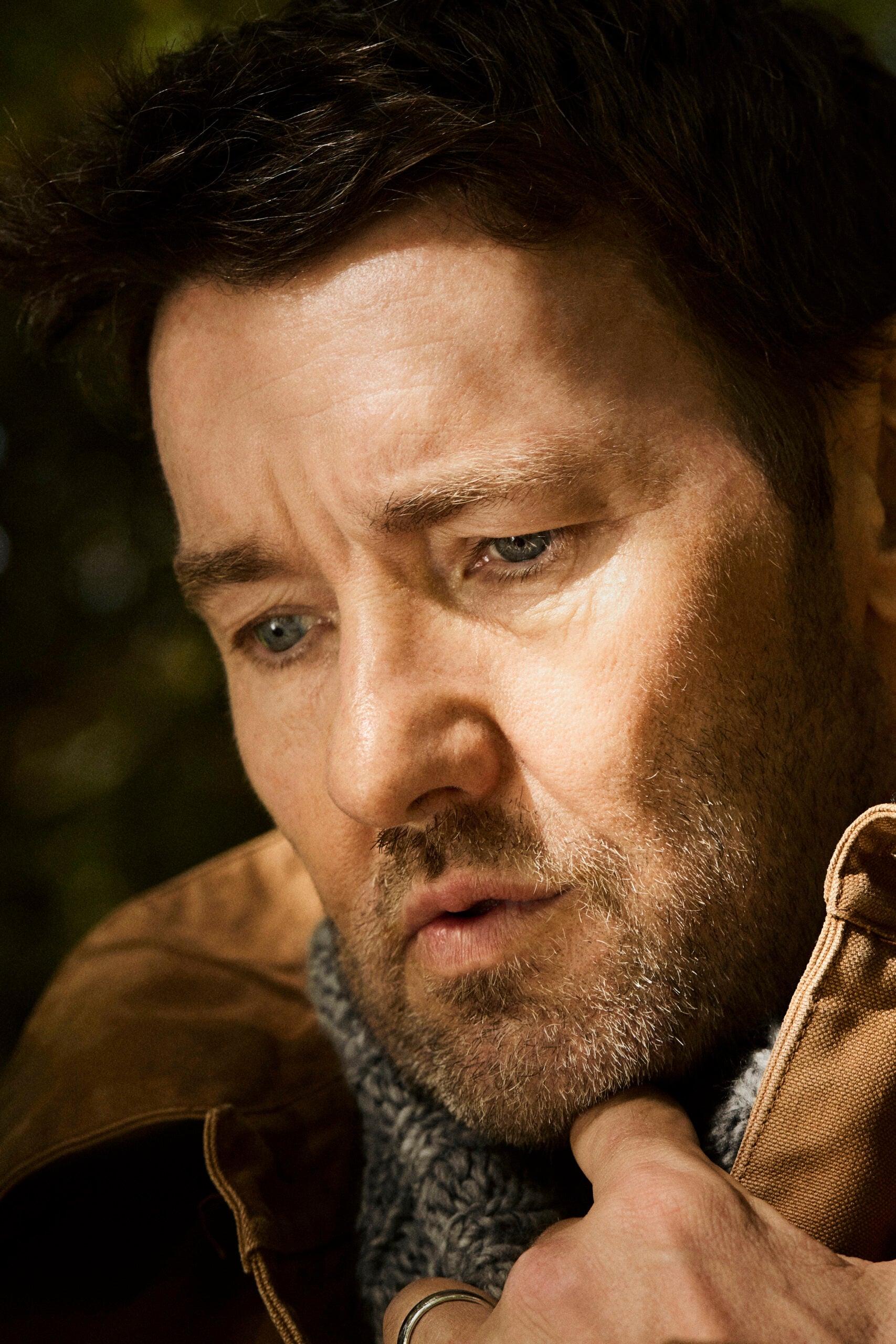

Joel wears a T-shirt by Merz B. Schwanen from Clutch Cafe London; vintage Air Force Jacket, Carhartt pants, neck scarf, and vintage boots, his own. STYLING BY MARK ANTHONY BRADLEY. PRODUCED BY ZRD PRODUCTION. (Photo: Neil Gavin)

There’s a particular kind of actor who feels equally at home in the wilderness and on the red carpet, who understands that the demands of the body and the demands of the spirit are not separate things. Joel Edgerton is that actor—someone who grew up on the edge of a vast forest in Australia, who ice plunges in London’s Hampstead Heath, who collects vintage military boots and speaks about the woods with genuine reverence. He is, in other words, someone who has never quite left the wild places that made him.

Over two decades, Edgerton has built a career of quiet virtuosity, the kind that doesn’t announce itself but accumulates like sediment: directing The Gift, a gem of a subversive psychological thriller; both producing and starring in award contenders like Loving and Boy Erased; and managing to steal the scene no matter how small or large the role, from Warrior to The Great Gatsby. He’s become that rare figure in contemporary cinema: an actor-director-producer whose work consistently operates at the intersection of craft and conscience. You get the sense that he’s always seeking the human truth.

In his latest project, Train Dreams, a Netflix release that is streaming now, Edgerton plays Robert Grainier, a logger and railroad worker whose life unfolds across six decades in the forests of the Pacific Northwest. Based on Denis Johnson’s luminous novella, the film follows Grainier from the turn of the 20th century through the 1960s as he witnesses America transform around him—railroads replacing horse trails, the wilderness giving way to civilization, his simple way of life becoming a relic. It’s a role that demands something rare: the ability to convey profound emotional depth through stillness, through the language of the body and the land itself.

Director Clint Bentley describes Edgerton as someone who “you feel like you could meet on a construction crew and he would fit right in as easily there as he does on a set of a Star Wars movie”. (Edgerton famously got his Hollywood start as Uncle Owen in Star Wars: Episode II—Attack of the Clones.) But there’s something deeper at work. Edgerton brings to Grainier a kind of authentic understanding—not just of labor or landscape, but of what it means to be a human being caught between two worlds: the person you are and the person the world demands you become. It’s a meditation on solitude, loss, and what it means to live in harmony with the natural world even as it disappears around you.

We caught up with Edgerton from his home near Hampstead Heath in London, where he’d just finished a photo shoot in that very park. Over the course of our conversation, we talked about wild places, what drew him to this story, and what it means to belong to something larger than yourself.

Outside: You’ve made your home near Hampstead Heath, where these photos were taken. What’s your relationship with that park?

Joel Edgerton: During the good parts of the year, I go down there with the kids most days. I’d put them in a box bike and ride them into the park, particularly when they were too young to walk. It’s rambly with all these different environments, but it’s mostly a forested kind of park, like a left-alone park, with pathways.

Occasionally, I get convinced by a friend of mine to go into the freezing cold ponds there and do a semi-Wim Hof kind of plunge.

Do you enjoy that?

I wouldn’t say it’s enjoyable, but I get something from it, if you know what I mean? I do it because I know that the feeling of the result is good. [Holds up a note.] Did the photographer tell you about this?

No, what’s that?

In the middle of a log, I found a note, folded and shoved in the middle of soil and wood chips. The writing is kind of prose but sort of poetry: “I was here, I followed every pull, every sign, every thread that led me to this spot”. And it ends by saying, “Maybe somewhere down the line you’ll pull too and find me”.

That’s remarkable—people leaving these intimate traces of themselves in the forest. Even in London, people are still seeking that connection with wild places.

Some people like to go and find solace and isolation, you know, use parks as a way to go and think about things. It made me realize, too, that even in a city, you can be lonely. You’ve got lots of people passing you every day, but you don’t know any of them.

There might be a movie in those notes for you. I noticed your Oura ring in these photos. How’s your sleep been?

My sleep score last night was only 59, which annoyed me like crazy. Travel affects things. But I’m determined to get more and better sleep. [The Oura ring has] changed my relationship to alcohol. And that has a lot to do with seeing your stats in the morning. I love the thing. I had to take it off my hand when I was shooting, but I’d wear it between scenes and through the night.

I didn’t know you were such a sleep nerd. I understand you’re into rock climbing as well?

I love it, but I have to admit to the fact that most of the rock climbing I’ve done has been indoors. I’m a little bit obsessive about it, but I’d put myself in the “OK” category with everything outdoors.

When did you get into the sport?

When I was in my early twenties. My brother was a stunt guy—still is—and he used to go up to the Blue Mountains in Sydney to do climbing and rappelling for work. I used to tag along with him. Then I started climbing when I was living in Melbourne. One time, I was on my way to this mountain range in Victoria to go climbing with some friends, and I got a call from the producer of the TV show I was working on. She asked, “What are you doing this weekend?” I said, “I’m just on my way down to the Arapiles to go climbing”. Her tone of voice changed. “No, you’re not. You’re not insured for that”.

Insurance getting in the way of fun.

Yeah, when you’re an actor, you often sign a clause in your contract, which says that you won’t engage in certain activities. They don’t want to be a month into shooting their show and find out you decided to go bungee jumping for the first time.

I like surfing, and I wouldn’t want anybody to tell me that I can’t do that. If you’re familiar with the thing and it’s part of the fabric of your life, then why would they try to stop you from doing that? Isn’t life kind of dangerous?

This film seemed physically demanding. You’re out there in nature, which is very much a character in this movie.

Yeah, it was. And I love that. The times I get to shoot movies in the wilderness feel comfortable because I grew up in a very rural place in Australia, right on the edge of Berowra Valley National Park. As a kid, I felt like there was no fence line between our property and the park—like we had the most expansive property in the world. That was my playground, this never-ending forest. The wilderness is tough for the crew and their equipment, but it’s not the toughest environment for an actor. It’s a real pleasure to be off the grid a little bit.

I imagine it’s like camping for work. Train Dreams is this spare, poetic novella—116 pages that somehow contain an entire life. What was it about Grainier’s story that made you want to bring it to the screen?

I was a big fan of the novella about seven or eight years before Clint even contacted me about doing the film. The book opens with Robert trying to wrangle a Chinese worker who’s supposedly done something wrong, and he participates in this act of violence without realizing what he’s doing. I thought: this is a Western. But it didn’t go down the typical roads of the retribution template. It became a philosophical rumination on life. That really got its talons into me.

The typical point of view on the modern history of America is that the Wild West was all about gunslingers in the desert. Train Dreams had a different aspect. The logging industry, the building of the railroads—it was less about good guys and bad guys and violence, and more about the journey and the hard work.

How did you prepare for the physical demands of the role? Did you spend time with loggers?

Clint and I shared something in common: his grandfather had been a logger, and my other grandfather had been a train driver. And my grandfather and great-grandfather came from a farming background—they were sheep farmers and bullock drivers. I’ve always felt an affinity for people who work the land because my life is relatively easy, and I spend it pretending to be people who are tougher than I really am.

Clint brought in a lot of guys involved in the logging industry, and we had really evocative materials from the era. When you look at photographs of the logging industry from the late 1800s and early 1900s, you realize just how hard that work would have been. Double-handed saws and axes, a team of ten or so men working on one monster tree. There are photos of seven or eight men, all lined up, sitting side by side in the wedge cut into a single tree trunk. You can only imagine how brutal that work must have been.

There’s something about manual labor in the wilderness that changes you—the repetition, the physicality. Did you experience any of that transformation during filming?

There was an interesting exercise when we first started putting Robert’s pack together. He’s out there for weeks on end, so we had to think: what would you put in one backpack if you had to make a journey for months? We chose the pragmatic objects—things you could cook with, his logging boots and axe, which is precious to him. And a few trinkets of sentimental value. Being out in the wilderness with your life reduced to one pack—I think it’s an exercise everybody should do, at least mentally. Ask yourself what is truly important. You realize how much of what we have isn’t really that important, and how much crap we accumulate. I’ve got so much crap everywhere.

If you had to go out in the woods for a month, what would be in your pack?

[Laughs] You just reminded me when we were kids, my brother had a spy kit and I had a survival kit. We’d go on survival courses for three days and learn how to start a fire and all that. But I’m not going on Naked and Afraid, that’s certain. If I were a real survivor, I’d take something to start a fire and a weapon. I’m not an advocate of guns, but if my life were under threat from savage animals or a zombie apocalypse? I’d have a gun. Something to sanitize water by boiling it. Plastic sheets to collect water—I remember wrapping a eucalyptus tree with a plastic bag overnight as a kid, and in the morning you’d have half a cup of fresh water. Shelter. Waterproof gear. I still feel like I’ve got two-thirds of my pack left empty.

Oh, I’d take some Vegemite.

Vegemite! Why? And for those who don’t know what Vegemite is, can you explain it?

It’s a salty, yeast-like paste you put on toast. I don’t know if it’s an acquired taste, but Australians either grow to love it or we’re built with different taste buds, because most people from other parts of the world are like, “Yuck”. But as my brother’s niece said, “Don’t yuck my yum.” I think it’s really good.

A lot of time passed between when you first read the book to making the movie. Did your perspective on Train Dreams change over time?

It’s funny how Train Dreams changed for me, and this is probably true of all literature and music—your perspective on art shifts at different points in your life. I was very taken with the novella when I first read it at 44. But I wasn’t a father then. Reading the novella and Clint’s and Greg Kwedar’s screenplay as a father, I found it more emotionally devastating. I didn’t have to imagine having kids to understand what it would be like to lose them. My relationship to the book completely changed, and I think it made me more suitable for the film.

One of the most powerful threads in the story is watching the wilderness literally disappear. The film has this interesting tension—it’s clearly historical, but it feels eerily modern too. Did making this film change how you think about our relationship with wild places?

The filming didn’t change how I feel about nature—I already believe the world needs to be treated better. But the film speaks to that in an interesting way through characters from decades past, with a spirituality that’s both naive and wise. William H. Macy’s character [Arn] has this instinctive understanding that the trees are ancient. He says it hurts a man’s soul to take down a tree like that. These ideas are naive but wise and rich.

Then Kerry Condon’s character, Claire, a conservationist, says that all of nature is intricately stitched together—organisms, animals, and humans are all part of the same ecosystem. “The dying tree is as important as the living one,” she says. Her ideas bring us closer to a modern understanding of the world as a delicate ecosystem.

I think we need active people and passive people. Heroes and conscientious objectors. Not all of us have the same interests or energy. There’s a balance to community—you’re good at this, I’m good at that. We need quiet, good-natured people in opposition to the selfish and self-absorbed. Sometimes those selfish people create progress. For every opinion, we need dissent. There’s conflict, but also a harmonious balance.

The film takes place in a more patient, less distracted time. What does that offer that maybe we’ve lost?

Movies often deal with dynamic action and explosions. This film shows you a place where characters talk about the world moving too fast. They’re facing the Industrial Revolution; we’re dealing with blindingly fast technological progression.

This movie takes us to a time when things were still and patient, devoid of technology. The movie theater itself is a sanctuary—probably the last place, apart from being completely off the grid, where we turn technology off.

The film addresses the violence and treatment of immigrants, the harvesting of the planet, and the emergence of new technology.

There’s a moment where Robert can’t get a petrol chainsaw to work, and he’s staring at it the way we’re staring at AI right now. While we’re looking back in time, the film is talking about things still relevant today—love, family, loss, but also immigration and technology.

Grainier is both an agent of environmental destruction—working to build railroads and clear forests—and someone who finds deep spiritual connection to nature. How did you navigate that contradiction?

It’s very easy as human beings to see ourselves as separate from or elevated above the earth and other animals. We can build and create things, but we’re also moving closer to destroying the planet. We see ourselves almost like some alien race lording over everything, rather than taking a more Indigenous perspective that we’re part of the land. It reminded me of these beautiful ideas and maybe amplified my guilt about how I’m not staying true to what I believe in, with coffee cups and plastic water bottles and all that.

There’s that line in the film, that’s directly from the book, “God needs the hermit in the woods as much as he needs the man in the pulpit.” How did you take that in?

And as Claire says right after that, “The dead tree is as important as the living one”. Decay is part of our natural evolution. When you hold things dear, it makes you vulnerable—personally and environmentally.

It’s ironic—I couldn’t get cell service in Laurel Canyon in Los Angeles, but when I visited Bhutan eight years ago, I got better reception in the mountains where I couldn’t see a single house. I don’t know that there’s anywhere left in the world where you can’t connect, unless you choose to.

So the movie theater is as sacred a space to you as the wilderness?

It’s a firewall to technology for me. Even if what I’m watching is created by technology, it’s transportation. Movie watching lets us put our imagination somewhere other than the past, present, or future. It takes us into another world, and that’s always been special to me.

Where did that imagination come from for you?

My brother was into early technology—the original Atari, the Commodore 64. But I always chose to go outside to the park, building weapons and pretending I was some medieval warrior. I could spend all day out there. I’ve never been a computer games guy. It was all about making my own fun and choosing my own adventure.

My childhood was watching tadpoles turn into frogs. I dream my kids get that in some way too. When I shoot movies like Train Dreams, it feels like a life that’s a little out of reach because to have it means turning off certain aspects of my work. But like Robert, there’s a way to puzzle the two things together.

There’s something about people who choose to live in wild places. What does Robert understand that maybe we’ve lost?

The film reminds you of how rich the world is to us and how precious it is, and how fragile. We need the creators and builders and active human beings, but the patient ones are also important. The peaceful, patient humans hold things more precious. Again, there’s that line: “God needs the hermit in the woods as much as he needs the man in the pulpit”. That illuminates something for me—the isolated human versus the communal one, the nonverbal one versus the verbal. A big part of my imagination was born out of where I lived. I dream my kids get that connection, that patience, that understanding that we belong to the land rather than owning it.