Netflix’s new documentary about the 2023 implosion of the submersible Titan reveals a preventable disaster years in the making. Titan: The OceanGate Disaster, premiering on June 11, shows how OceanGate CEO Stockton Rush forced forward a fatally flawed design. Whether it was his commercial interests, or his own hubris, something compelled Rush to ignore safety measures, which ultimately led to the death of five people.

I covered the Titan submersible years prior to its implosion, interviewing Rush multiple times before the disaster, and I also contributed to Outside’s coverage when the sub went missing. So I watched the film with a careful eye, curious if it would shed new light on the incident.

The film examines efforts Rush put toward silencing his critics. It also reveals how clear it was for years that the sub was never capable of repeatedly making safe trips to the Titanic, and Rush’s determination to ignore all warnings. Jaw-dropping footage and interviews shows he was willing to risk lives, including his own, in service of making OceanGate the Space X of the sea.

Released nearly two years to the day after Titan went missing, this documentary unveils shocking decisions that led to the ill-fated journey, a disaster that continues to captivate the world years after the fact.

Blatant Disregard for Safety and Hubris Led to Disaster

The documentary reveals how Rush’s original sin was also a mortal one: Building Titan’s hull out of carbon fiber to save money. Carbon fiber is essentially long chains of carbon twisted together like a yarn, then coated in glue or resin. It has a great strength-to-weight ratio, meaning the sub was much lighter and smaller than your typical build. That made it cheaper to transport, and affordability was a key part of his business ambitions.

Early in the film, Bonnie Carl, OceanGate’s accountant, reveals that Rush hoped to become a “big-swinging dick” that changed the world, on-par with Jeff Bezos or Elon Musk.

But the Titan’s cheaper hull had a flaw. Carbon fiber can have air pockets, and its fibers can snap when under too much pressure. The Netflix documentary shows Rush and others conducting topside pressure tests in partnership with Boeing on scaled-down models of the submersible. The first model implodes before reaching Titanic-levels of pressure, and the second one buckles even faster.

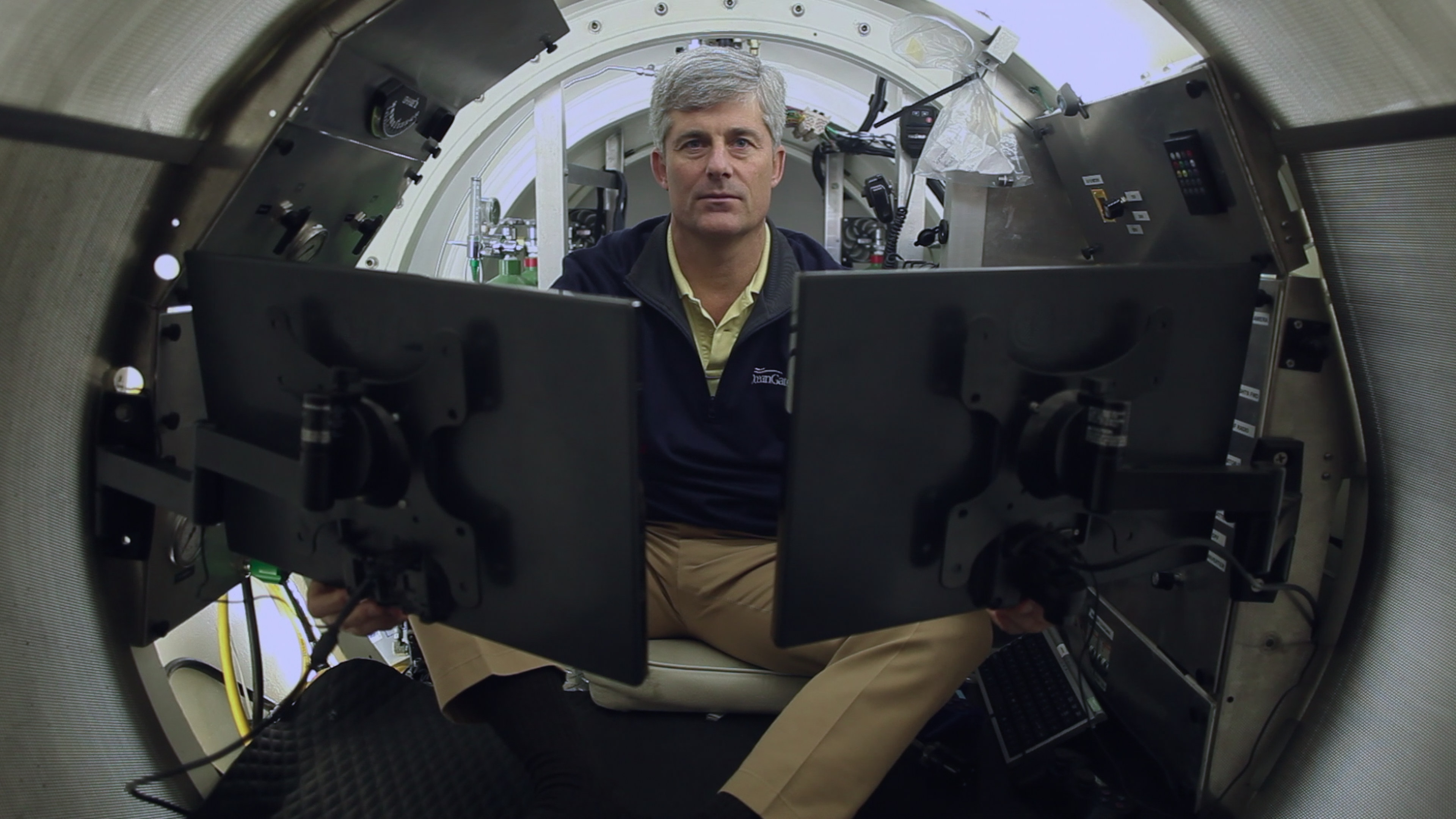

Still, OceanGate moved forward with a full-size hull. In shocking footage of Titan’s first deep ocean dive, featured in the documentary, Rush is piloting the sub solo. You can audibly hear the carbon fiber hull popping and snapping.

My jaw dropped as I watched Rush acknowledge the sound (“Man, what the f*ck?”), brush it off (“That’ll catch your attention.”), and continue his descent (“As long as it doesn’t crack, I’m okay.”)

“Because anybody that’s been in a submersible—anyone that’s worked with subs—knows that’s the sound of your death approaching.”–Rob McCallum

Rob McCallum, a submersible expert, had a similar reaction. “I was sitting in the theater with Dave Lockridge [at the film’s premiere], and when that noise was playing, I actually gripped his knee, and I said, ‘Holy shit. How did he do that?’” McCallum tells me on a phone call. “Because anybody that’s been in a submersible—anyone that’s worked with subs—knows that’s the sound of your death approaching.”

This moment encapsulates Rush’s single-minded fixation with bringing his vision to life — reality be damned. He repeatedly ignored experts warning of evident issues, from Boeing engineers to McCallum. And he habitually dismissed staff who questioned the operation. Before the open water tests, he fired Lockridge, his director of maritime operations, for documenting potentially dangerous problems with the vessel. And he made it clear to those within OceanGate nobody would get in his way.

“He said… that if the Coast Guard became a problem he would buy himself a congressman and make it go away,” Matt McCoy, an OceanGate operations technician in 2017, testifies during the film.

OceanGate’s director of engineering, Tony Nissen says Rush told on the very day he fired Lockridge that “it would be nothing for him to spend $50,000 to ruin somebody’s life.”

“That changed my life in that company,” Nissen says in the documentary. “It changed how I managed the engineering department. I had to make sure that nobody spoke up. I worked for somebody that was probably a borderline clinical psychopath, but definitely a narcissist.”

Rush continued to test OceanGate’s popcorn hull with people aboard. It eventually cracked during a dive in the Bahamas. He responded, the film shows, by dismissing several members of the engineering staff, including Nissen. OceanGate then made another carbon fiber hull and shipped it to Nova Scotia for expeditions.

Nissen didn’t alert anyone that they were deploying a sub design proven to fail. “I wasn’t going to fight him. I wasn’t going to go to the board, because Stockton stated clearly how he likes to ruin a life,” Nissen tells filmmakers.

The company’s one nod to the sub’s tendency to snap under pressure was to install a network of microphones throughout the sub that recorded the volume of each break.

Rush “was angry I did that,” Nissen says in the film.

In theory, the system would allow the team to separate what they accepted as standard pops from something more concerning. “What I couldn’t understand is, what’s the point?” Mark Monroe, the film’s director, tells me in a recent interview. “If no one has ever taken a carbon fiber submersible down to these depths, then how do you have a baseline of the noise” that is acceptable and what would signal a problem worth surfacing?

The system ultimately did deliver a clear warning. It was ignored.

The film shows that, during the end of Titan’s 80th dive, those inside heard a major noise as it approached the surface. It has since been determined this was likely delamination of the carbon fiber (separation of its layers), which significantly weakened the hull. The audio monitoring system captured the disturbance, but OceanGate ignored it.

“It is, in my mind, the smoking gun of what eventually caused this,” Captain Jason Neubauer, the U.S. Coast Guard Investigator overseeing the case, says in the film.

Documentary footage aboard the support vessel after dive 80 shows Rush mitigating the issue: “At Mission 4, when we got to the surface, Scott was piloting and we heard a really loud bang. Not a soothing sound. But on the surface. But as Tim and [Tiantic expert] P.H. [Nargeolet] will attest, almost every deep-diving sub makes a noise at some point.”

Titan imploded on its next deep dive.

The U.S. Coast Guard is still investigating the incident. Results are expected later this year. The final report will lay out the official determination of what happened, why it happened, and likely include recommendations for what needs to change to keep it from happening again. Depending on its findings, the case could be referred to the U.S. Justice Department for criminal charges.

“I think there is a part of the world that admires people who move past and break things, that don’t play by the rules,” Monroe said. But “there are some rules that do apply to all of us. Those are the rules of nature, the rules of physics, the rules of science. You can’t skirt those rules, and when you try to, bad things happen. And that’s what happened.”

Why Are We Still Obsessed with Titan?

The new film raises a question in my mind: Why are we so willing to help a few people in an instant crisis, but unwilling to help the scores of people facing slow-moving tragedies we ignore every day?

At least five countries mobilized to search an area larger than the state of Connecticut. The U.S. spent $1.2 million on the search, while Canada’s coast guard shelled out $3.1 million. These same agencies would typically debate such expenditures to help thousands of their own citizens. Yet they dropped those resources for five people from multiple countries in an instant.

You can see this phenomenon play out in other dramatic rescue situations. The whole world watched when Baby Jessica was stuck in a well in the late eighties, when a mine collapse sealed Chilean miners underground for 69 days in 2010, and when the Thai soccer team got trapped in a flooded cave in 2018. The Thailand cave incident inspired two films, yet other tragedies don’t always catch the world’s attention.

To make sense of this mismatch, I turned to Dr. Paul Slovic, a pioneering psychologist at the University of Oregon who has spent decades unraveling the mysteries of human compassion and indifference.

“Emotion is the major factor, and…it doesn’t respond to the scale of the problem,” he says.

In fact, emotions do the opposite, shutting down as the problem grows. “Our research shows the more who die, the less we care,” Slovic says. He calls it “the arithmetic of compassion“—a flawed emotional calculus that leads us to underreact in mass crises, but leaves us equipped to act when a few people need help.

As situations grow in complexity and scale, “pseudoinefficacy” can take hold; we become so discouraged by our inability to help everyone that we end up doing nothing at all. Small contributions are abandoned, even if they are meaningful. They just feel too insignificant in the face of overwhelming need.

At the same time, our capacity to care diminishes as the number of people affected increases, a paradox known as “psychological numbing.” Our brains are more attuned to the suffering of the few than that of the masses, Slovic adds. And the longer something goes on, the more we numb to it.

Rescue stories, like that of Baby Jessica or the Thai soccer team, generate massive public engagement because they focus on a few people we connect with, are time-bound, have a clear-cut resolution, and people feel there is a real chance of solving the problem.

Titan’s tragic ending had all the elements to capture our compassion: Five faces, a countdown clock, a clear-cut definition of success, and a sense that there was hope.

But that is not the only lesson Slovic’s research has for us when it comes to Titan. Everything leading up to that dramatic implosion mirrors the slow-moving crises we ignore every day. People saw the danger but either stayed quiet, looked away, or were pushed out. The slow creep of risk was tolerated, normalized, rationalized, until it became irreversible.

In that way, OceanGate isn’t an outlier. It’s a mirror.

We live in a world full of slow-moving disasters: climate change, systemic poverty, public health crises. We see the data. We hear the warnings. But action comes late, if at all, because urgency is hard to sustain when collapse doesn’t happen all at once.

That’s why Titan still grips us. Not just because it’s a story of audacious risk and avoidable death, but because it reflects something uncomfortably familiar. OceanGate may be gone, but the systems that doomed it are still all around us.

___________________________________________________