If you buy through our links, we may earn an affiliate commission. This supports our mission to get more people active and outside.Learn about Outside Online's affiliate link policy

Gen Z Just Figured Out What Boomers Already Knew—Cottage Cheese Slaps

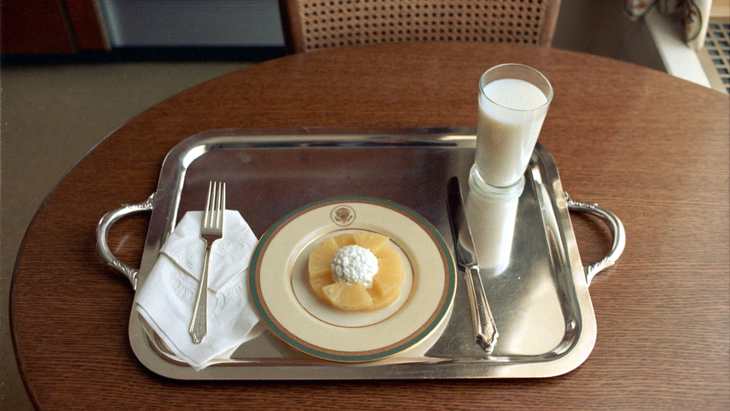

(Photo: Left: Canadian-American actress Ann Rutherford (1917 - 2012) prepares herself a pineapple and cottage cheese salad sprinkled with paprika, circa 1939, Archive Photos/Getty Images; Right: Cottage cheeses: Trader Joe's, Daisy Brand, Good Culture; Design: Ayana Underwood)

I have a confession: in the middle of my 75 Hard spiral—a social media-sanctioned self-optimization grind disguised as a fitness challenge—I made queso. Not just any queso. Cottage cheese queso. This is a sentence I never thought I’d write.

I started the challenge this past February—partly to beat the winter blues in the Northeast, and partly because I needed a reset after taste-testing one too many of Santa’s cookies. I was committed to said challenge. This meant: doing two 45-minute workouts (at least one of them outdoors), reading ten pages of a nonfiction book, and drinking a gallon of water . . . each day. Most intimidatingly, I was supposed to stick to a diet of my choosing. I went all in: HIIT training, 4.5-mile runs, Becoming Supernatural queued up on my e-reader, and a squeaky-clean keto plan that had me eating organic, grass-fed (and grass-finished) beef that I could barely afford. I tracked macros and considered electrolyte ratios. I had come to terms with the fact that I’d become someone who used the term “electrolyte ratios” in casual conversation.

And then I burned out.

Somewhere around Day 42, I traded mountain climbers for Yin Yoga. I prioritized taking long walks, watching white-tailed rabbits hopping alongside the estuary near my home in Boston, Massachusetts, over chasing yesterday’s personal best. The diet? That crumbled when I tried to justify the cost of avocados and eggs and failed. (Within the last year, the price of a single avocado rose by 75 percent, and the usual three bucks I’d spend on a carton of eggs turned into five.)

Similar Reads

Still, I wanted to eat well(ish), which for me, means protein-heavy, low-effort, and ideally not financially ruinous. So, like any overstimulated elder millennial trying to avoid decision fatigue (and wear sunscreen, and hydrate, and remember to call mom), I turned to Instagram.

Welcome @KetoSnackz to the chat. With 3.5 million followers, Rick Wiggins shares quick, high-protein recipes meant to satisfy cravings while staying protein-powered. His creations looked suspiciously easy. His voice was refreshingly monotone. I was in.

As I scrolled, one ingredient kept popping up, an ingredient I found personally affronting: cottage cheese. It was white and lumpy. It was wet. It was everywhere. Rick blended it into pizza crusts, brownies, and pancakes. And it wasn’t just on Rick’s page. TikTok, too, had fully surrendered to the curd—which was confusing. Because for me, I never saw it in my Caribbean household growing up. My parents didn’t eat it. We didn’t cook with it. To borrow from Mariah Carey: I don’t know her.

The message? This is food you eat because it’s good for you.

So when I made queso out of it (blended with cheddar, cream, taco seasoning, and hot sauce) and served it to a friend while hanging out, I didn’t tell them what was in it. They liked it. Called it “fire.” Then I broke the news.

They looked at me like I’d confessed to putting mayonnaise in brownies: “Wait . . . like, real cottage cheese?”

“Yes. From a tub. Bought on purpose.”

I was surprised, too, because the queso was, in fact, fire. But I was also curious. Because how did goat cheese’s sad, curdled step-cousin become America’s newest protein-packed heartthrob?

I. TikTok, but Make It Clumpy

In April 2023, holistic nutritionist Lainie Kates—@lainiecooks on TikTok and one of the creators credited for the renewed interest in cottage cheese—posted a high-protein peanut butter cheesecake “ice cream” recipe. In it, she blended cottage cheese, peanut butter, chocolate chips, and maple syrup. Froze it. Ate it. Her video went viral. The internet was flooded with cheesecake bowls, ranch dips, and “protein donuts”—most of which starred cottage cheese. It didn’t matter that the texture was off-putting. It blended well. It hit macros. That was enough.

Then brands caught on. In 2024, Daisy, sour cream’s shepherd, partnered with The Bachelor’s Daisy Kent to promote the brand’s equally famous cottage cheese.

Just this month, Trader Joe’s dropped Ranch Cottage Cheese Dip. Good Culture, a brand started in 2015, was literally born out of the desire to bring a revamped, better-tasting, and healthier version of cottage cheese to the public. A few weeks ago, they put out a meme-laden statement on Instagram saying that they can’t keep up with the demand for their iconic cottage cheese, confirming the cheese’s renewed popularity.

The message? This is food you eat because it’s good for you—crafted with “good-for-you-ingredients,” made with only “the good stuff,” and “a versatile bit of dairy capable of providing protein and texture.” That’s how the brands framed it. And if the messaging sounds familiar, that’s because we’ve heard it before.

II. A Short History of a Long Shelf Life

In the early 1900s, the U.S. had a problem: meat was scarce during World War I. To help conserve it, the U.S. Department of Agriculture promoted dairy as a substitute. Posters encouraged people to “Eat More Cottage Cheese.” It wasn’t just a suggestion; it was patriotism.

By the 1950s, cottage cheese had migrated from the war effort to weight-loss plans. It was low in fat, high in protein, and flavorless enough to avoid overindulgence. You could measure it. You (probably) wouldn’t overeat it. Thus, it was ideal for calorie counting.

That’s right around the time when the “diet plate” made its way to America’s diner menus—usually a scoop of cottage cheese, a ring of canned peach or sliced tomato, maybe a wedge of iceberg lettuce. It wasn’t really a meal. It was more of a performance. A way to show you were being good. These plates lingered well into the seventies and eighties, eventually evolving into the “Lite” menu I remember seeing at Long Island diners during my childhood in the nineties. Same scoop, same canned fruit—just rebranded for the next generation of restraint.

Cottage cheese didn’t evolve. It was just repurposed. And maybe that’s the clearest sign of its legacy: it survives not by being loved but by being useful.

By 1972, Americans were eating about five pounds of cottage cheese per person each year. Even Richard Nixon was known to pair his with ketchup. YUM. He had such a lust for lactose, in fact, that he reportedly requested cottage cheese at his 1969 inauguration dinner. And when he resigned from office in 1974? His final White House lunch was cottage cheese with pineapple and a glass of milk. A presidency bookended by curds.

III. Who Was It Really For?

Not everyone was eating it. Rather, not everyone was meant to be eating it. Mid-twentieth-century food campaigns primarily targeted white, middle-class women. Cottage cheese came with a message—eat this, stay thin, stay beautiful, stay in control.

Cottage cheese was sold as a democratic food: cheap, accessible, healthy. But it never belonged to everyone.

Even when it showed up in government campaigns and school lunches, it wasn’t a staple in every home. It simply didn’t catch on in many immigrant, Black, and working-class communities. Part of that was logistics. Cottage cheese requires refrigeration, fresh milk, and a cold distribution chain, not always available in rural or low-income areas.

Look at the ads. White women in full makeup, smiling at tubs of cottage cheese like they’d just invented it. One Eden Vale ad shows a nuclear family floating through a suburban utopia, landing at a table set with cottage cheese salads and a big tomato. A Knudsen ad features a flawless woman offering a tub of “VELVET creamed cottage cheese,” promising sweetness, lightness, and domestic perfection. Borden’s went all in: cartoon cows, crisp lettuce, and cottage cheese rings studded with peas and carrot sticks. No spice, no mess—just a carefully styled portrait of control, domestic order, and cultural exclusion.

These images weren’t neutral. They reinforced the message: this is who eats this, and this is how you serve it. In her 2011 book, Food Is Love: Food Advertising and Gender Roles in Modern America, historian Katherine J. Parkin argues that mid-20th-century food advertising reinforced narrow ideals of femininity, pressuring women to equate thinness, domestic perfection, and family nourishment with personal value.

But the bigger issue was taste. Cottage cheese didn’t reflect the ingredients or textures of most non-white food cultures.

My Caribbean family’s fridge, for example, held sorrel, pepper sauce, and mango chutney, not clumps of dairy. So, when I brought home a container of Good Culture to recreate my (self-proclaimed) famous queso, they looked at it suspiciously. Then they asked what I planned to do with it. When I said “queso,” they raised their eyebrows and sucked their teeth. They weren’t offended. Just confused. It’s understandable because the marketing never spoke to them. And it wasn’t designed to.

IV. Cottage Cheese Loses Its Steam

Even among the people it was supposedly for, cottage cheese couldn’t hold on.

By the 1980s, its popularity started to slide—quietly edged out by a new dairy star with smoother texture, stronger marketing, and fewer identity issues: yogurt. High in protein, rich in backstory, and aggressively rebranded as a probiotic superfood, yogurt didn’t just enter the chat—it took over the conversation.

Cottage cheese didn’t know how to compete. There were no new formats, no updated flavors, no attempt to win over younger shoppers. It stayed in its big old tub, parked on the fridge shelf. Meanwhile, yogurt was out living its best life—popping up as Go-Gurt in school lunchboxes, and with glass jars with foil lids in meal-preps. One became a lifestyle product; the other stayed a buffet-line staple at your grandmother’s favorite salad bar.

The texture didn’t help. In a 2012 study published in the Journal of Dairy Science, researchers found that texture was the biggest barrier to cottage cheese acceptance, especially among younger consumers. The graininess, visual lumpiness, and curdy mouthfeel turned people off, even when the fat and protein content hit all the right numbers. Even versions labeled “low-fat” or “high-protein” couldn’t overcome the basic sensory mismatch. People didn’t hate what it stood for. They just didn’t want to eat it and feel it on their tongues.

At the same time, yogurt brands were investing in stories. Chobani was founded by an immigrant entrepreneur who turned a struggling factory into a billion-dollar company. Dannon built a whole campaign around Georgian centenarians and the secret to long life. Yogurt had a point of view. Cottage cheese didn’t even have a spokesperson.

By the 2010s, yogurt was outselling cottage cheese nearly eight to one. And cottage cheese wasn’t just fading in market share—it was fading in memory. It stopped being an expectation. For most people, it stopped being an option.

So when it started trending again—sneaking into dips, desserts, and TikTok reels—it felt less like a comeback and more like a glitch. Cottage cheese didn’t evolve. It was just repurposed. And maybe that’s the clearest sign of its legacy: it survives not by being loved but by being useful.

V. Diet Culture, Rebranded

Today’s cottage cheese wave still centers on the same values: control, efficiency, and self-regulation. The language changed, but the pressure stayed. It’s no longer “stay thin for your husband,” it’s “optimize your macros.”

The look changed, too. It’s not a scoop on a peach slice. It’s whipped, blended, hidden in dips, ice creams, and sauces. It’s in a glass bowl, drizzled with chili crisp and tagged #highprotein on an influencer’s “What I Eat in a Day” reel. But the performance is the same: eat this to prove you’re doing the work.

We used to count calories (some people still do). Now we count macros. We used to tally Weight Watchers points. Now we use apps and fitness watches to track calories burned. We used to aim for thin. Now we say lean.

Blending until smooth is a requirement. The texture is still a problem, it’s just one we’re now expected to fix. And the brands know that.

Cottage cheese itself still needed a rebrand—not because it was forgotten, but because it was never truly loved. It has to justify itself because it can’t rely on flavor or nostalgia.

Modern cottage cheese branding sells function first: gut health, low carb, high protein. The packaging often mirrors wellness trends—clean lines, block fonts, neutral palettes—the same aesthetic you’d find in a Scandinavian furniture showroom. Some lean into compliance culture, highlighting Whole30- or keto-friendly ingredients. Others soften the message by adding flavor cues, but even then, pleasure is usually positioned as a bonus, not the point.

Take Trader Joe’s ranch cottage cheese dip: “a fantastically flavorful dip,” yes—but only after mentioning its protein content, versatility, and use in pancakes, pasta, and frittatas. The indulgence comes with an asterisk. It’s not just tasty—it’s functional.

I’ve tried the Good Culture stuff. It’s fine. It blends well. But cottage cheese itself still needed a rebrand—not because it was forgotten, but because it was never truly loved. It has to justify itself because it can’t rely on flavor or nostalgia.

Maybe that’s why it fits so well into modern wellness culture. We’ve replaced calorie charts with meal-prep hacks. But the goal remains: Build a better body. Be a better person. Stay in control.

Cottage cheese still fits that mold. Just like it always has.

VI. Reflection: The Cheese That Refused to Quit

I didn’t expect to end up here—with a half-used container of cottage cheese in my fridge and a short list of recipes I’m not embarrassed to share. I still don’t love it. I don’t crave it. But I’ve learned to respect it.

That respect came from looking back. Cottage cheese didn’t trend because a TikToker froze it into a dessert. It’s been around for over a century, always showing up when we decide food should prove something. War, weight loss, wellness—cottage cheese shows up to work. (FYI: I explain some even more extraordinary uses for cottage cheese in the video below.)

Once it was about thrift. Then self-denial. Now it’s optimization. But the message doesn’t change: If you eat this, you’re trying. You’re disciplined. You’re doing it right.

And that’s why it still makes people uncomfortable.

You don’t have to explain why you like donuts. But cottage cheese? You need a reason. High protein. Gut-friendly. You don’t just eat it, you earn it.

Whether I’ve earned it or not, I’ve blended it into queso. Stirred it into pancakes. Eaten it—very reluctantly—by the spoonful. Once. I’m not a fan.

But I’m not against it anymore, either.