This Sunday, April 28, will see the 39th running of the London Marathon, an event that has hosted some of the world’s greatest races. Eminent running writer Roger Robinson was there for many of them. Here, he reflects on two superlative world records set in London in 2002, in an excerpt from his new memoir, When Running Made History.

The intensity and passion and suspense of the London races in 2002 were the stuff of legends. Asked later if she would be watching a video of her run, Paula Radcliffe said, “I doubt it. I have it in my mind.” It is in the minds of all who witnessed it.

It remains there with such clarity partly because London that year was the first marathon to start the elite women’s field ahead of the men. So they raced on their own terms, not paced and protected by attentive or attention-seeking men. The crowds and the media could watch them uncluttered. The best women were allowed the risk and responsibility of being alone.

So Radcliffe was unimpeded, when after nine cautious miles her patience ran out, she lifted those bony knees, and pranced away from Derartu Tulu and Susan Chepkemei. Alone she did it.

Alone she took the awesome responsibility of that move, with the watching world clucking. Alone she ran for seventeen miles, with the thought, as she later confessed, with her typical directness, “You’d better not blow this, or you’ll be the idiot who didn’t respect the marathon.” Racing is about judgment, decision, responsibility, risk, sometimes loneliness. No woman could better embody those qualities than Radcliffe.

Racing marathons is also about balancing passion with caution. After passing halfway eighty-three seconds ahead in 1:11:04, Radcliffe smelled home, like a spirited thoroughbred. She surged from a 5:25-mile canter to two galloping 5:06s. But wisdom prevailed.

“When I saw 5:06 I thought, whoops, better slow it down,” she said. The wondrous 2:18:56 outcome confirmed her judgment.

A year later on this same London course, with help this time from male pacers, Radcliffe fulfilled her supreme potential. Driving as only she could through all barriers of pain and doubt, she obliterated the world record with 2:15:25. That stands, sixteen years later, as one of the superlative performances in running history.

Paula was a celebrity on a scale I’d never seen before in this sport, not even Grete Waitz in New York. In 2002, in the last ten miles, we were gripped with suspense as she ran into undiscovered country. Radcliffe’s risk-taking attitude and the way she sometimes got herself into trouble always made me think of the old silent movie series, “The Perils of Pauline.” Millions watched our Paula sob when injury put her out of the 2004 Olympic Marathon, millions more watched her suffer diarrhea during the 2005 London Marathon. Winning is not easy, not always pretty. Radcliffe has proved in public that with the responsibility of racing goes risk, and that running’s women have redefined being feminine.

The best way I can describe the London weather conditions in 2002 is to say that there weren’t any. No heat, no cold, no humidity, no wind, just 48F/9C of English mildness. Nothing to deter the men’s race from being worthy of the field assembled, which is saying a lot. From the first mile in 4:47 they ran on the very cusp of world record speed. Even more surprising was that at 62:47 for half-way there were still twelve there, several setting major personal bests at that point.

Finally, as they raced along the Thames toward Westminster, only the big three were still in it: Haile Gebrselassie, running his first marathon, multiple track and cross-country gold medalist Paul Tergat, and world record holder Khalid Khannouchi. From that moment—the 23 miles mark on April 14, 2002—those three would monopolize the world marathon record for the next decade. Khannouchi broke it that day, Tergat claimed it in 2003, Gebrselassie took over in 2007, and put it under 2:04 in 2008.

That threesome moment in London proved historic. At the time, all we knew was that three of the greatest runners the world has ever seen were skimming with that sublime fluidity of great marathoners along the Thames Embankment. Utterly unlike in origin, physique, running action, and personality, they demonstrated that we need better definitions than merely “African.”

Later, at the press conference, I asked what each had been thinking at 24 miles, when no one in the world knew how it would end. Their answers were revealing.

Khannouchi: “You know you are in pain, but I was thinking, I can go those two miles. I felt I betrayed a lot of people by dropping out of the world championship last year. Everything then was dark for me. Now I wanted to give the United States something better than a medal.”

Tergat: “I was thinking, these are people with a lot of experience. I was thinking, something is going to happen. And it did.”

Gebrselassie: “I was thinking, to win would be wonderful. I was thinking about being in front. But I could not.”

And that is exactly how it looked. Gebrselassie the demigod suddenly got that puzzled frown and stiffened stride we mortal runners know so well. He drifted. Tergat, with his perpetual nemesis beaten at last and the world for the taking, could not make the decision to take it. He waited. It was Khannouchi, a man in search of identity and acceptance, who was impelled to seize control, and pay any price in effort and pain to keep it. He prevailed.

Three times in the last mile he looked anxiously behind, fuelled by fear, seeming to be more conscious of the potential of Tergat’s sprint than Tergat was. Khannouchi earned his new US passport with a world record, four seconds under his own 1999 Chicago mark, the only American to hold it since Buddy Edelen thirty-nine years earlier. As he modestly said later, “winning does not alone make me the greatest.” But when you want to gain acceptance in America, it sure helps.

As for Paula, as everyone calls her, the ultimate English heroine, the ordinary girl-next-door yet capable of the extraordinary; extremely intelligent, with a first-class degree in languages and so confident that I’ve seen her conduct a media conference in alternating French, German and English; always astute and scientifically informed when you ask about her training and racing; openly tearful when she is unlucky or fallible, yet more often radiantly triumphant; charismatically vibrant when that intelligent enthusiasm shines forth; talented, yet her biggest talent is a huge capacity for sheer hard work. In wartime she would have been a leader, innovator, and heroic medal-winner. Now she has run her last elite race, the best thing the Brits could do would be what they have done for other female icons, like Britannia, Queen Victoria, and Nell Gwynne—name a pub after her. No more fitting tribute than a pint at The Paula Radcliffe somewhere between Tower Bridge and the Mall.

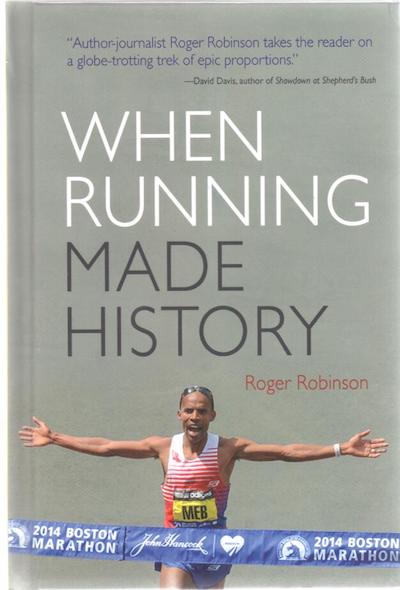

Excerpted and adapted from When Running Made History, a first-hand account of 60 years of significant moments in running history, acclaimed as “the best running book of all time” by Amby Burfoot.