Carbohydrate ingestion—and its subsequent digestion, absorption, and delivery to skeletal muscle—is imperative for maintaining carbohydrate burning during intense exercise that lasts longer than 60–90 minutes. As carbohydrate stores in your body dwindle, rates of energy production and muscular contraction decline because slower-burning fatty acids become an increasingly dominant fuel source. Consequently, ingesting carbohydrate helps maintain higher absolute workloads during intense, prolonged exercise.

There is a natural limit, though, to the amount of carbohydrate you can digest and absorb over any given period. The absorption of carbohydrates is facilitated by protein transporters in the outer wall of the cells that line your small intestine. These transporters act sort of like off-ramps on an interstate, and as many of you know from your own experience, traffic congestion can lead to major commuting problems. Similarly, overloading the gut with carbohydrate can overwhelm these transporters, leading to the equivalent of a traffic jam in your small intestine.

In other words, if you consume too much carbohydrate during exercise, symptoms like abdominal cramping, diarrhea, bloating, and flatulence may develop. This is because unabsorbed carbohydrate draws water into the intestinal lumen and is eventually fermented in the colon, with loose stools and gas production as the unfortunate by-products.

Two of the key transporters when it comes to absorbing carbohydrate during exercise are known scientifically as SGLT1 and GLUT5. The SGLT1 transporter is responsible for absorbing glucose molecules, while the GLUT5 transporter has an affinity for fructose. Importantly, each of these transporters can only handle about 40-50 grams of carbohydrate per hour. Consequently, ingesting a mix of carbohydrate types (glucose plus fructose), as opposed to just one, is recommended—at least when you plan to consume more than 50 grams per hour. To give some perspective, a typical sports gel contains 20–25 grams of carbohydrate.

Can You Train Your Gut?

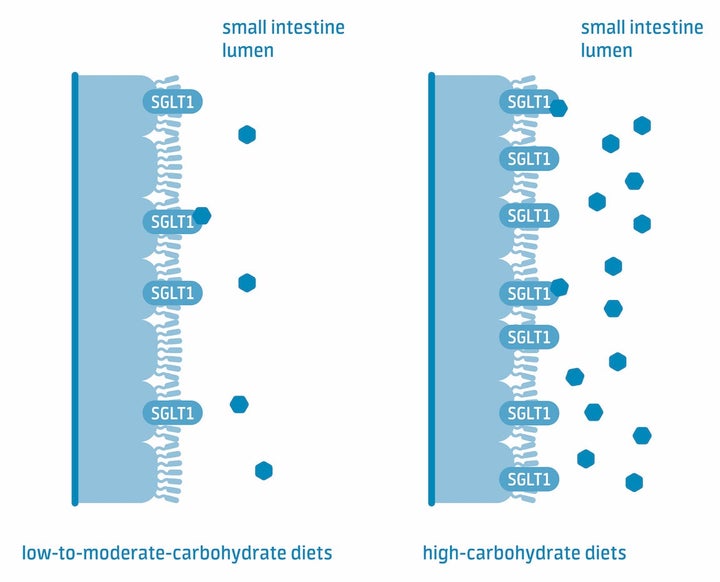

One intriguing question is whether it’s possible to train your gut to increase the capacity of these transporters, which would allow you to increase the amount of carbohydrate you absorb and burn during exercise. As discussed in an eloquently written paper by sports scientist Asker Jeukendrup, an abundance of data from animal studies makes it clear that the activity and/or concentration of these transporters can change based on the carbohydrate content of the diet. Simply put, more carbohydrate in the diet equals more of these transporters in the intestines.

Data directly confirming that this also happens in humans are lacking, in large part because isolating these transporters requires excising a sample of intestine. Even so, there’s some indirect evidence that this adaptation also happens in the intestines of humans.

Take a study from the Australian Institute of Sport that tested whether feeding a four-week high-carbohydrate diet would increase athletes’ capacities to burn carbohydrate eaten during exercise. Athletes assigned to a high-carbohydrate group consumed glucose drinks before and during training sessions while athletes allocated to a moderate-carbohydrate group consumed fat-rich foods (macadamia nuts or a cream drink) after training sessions. Importantly, both diets provided the same total energy.

At the start and near the end of the four-week dietary period, the athletes completed a 100-minute cycling test while consuming a beverage containing a special form of glucose that can be traced in the body. The experiment ultimately revealed that the high-carbohydrate diet increased the oxidation of traced glucose by 16 percent, with no apparent change on the moderate-carbohydrate diet.

The researchers concluded that enhanced intestinal absorption of glucose was the most likely explanation for this finding. In terms of practical guidelines, studies—albeit using animals—have found that just a few days on a high-carbohydrate diet can upregulate intestinal transporter expression, meaning you probably don’t need to crush carbohydrate for weeks straight to see these changes.

Does Better Transport = Better Performance?

While mounting evidence supports the notion that eating a high-carbohydrate diet boosts the quantity and/or activity of intestinal carbohydrate transporters, these adaptations’ implications on performance are less clear. In fact, that same study from the Australian Institute of Sport also measured performance and failed to find any differences. One potential reason for this is that the moderate-carbohydrate diet still contained a good amount of carbohydrate; if the comparison diet had been low carbohydrate, it’s possible that even larger differences in carbohydrate burning would have been observed, which could have led to meaningful changes in performance. That said, one recent study conducted by researchers at Monash University in Australia did find improvements in running performance after two weeks of a carbohydrate-based gut-training protocol, and these improvements were likely mediated through reductions in digestive symptoms.

Overall, these studies tell us that training your gut to tolerate more carbohydrate during exercise could translate to improvements in not only carbohydrate burning and digestive symptoms, but also possibly performance. An important caveat to this statement is that it applies to athletes who are planning to push the envelope of carbohydrate ingestion during competition (i.e., more than 50 grams per hour). If you plan to consume 30–45 grams of carbohydrate per hour, there’s little reason to do this sort of aggressive gut-training protocol.

Emptying the Stomach

Beyond affecting the intestine’s capacity for absorption, the carbohydrate content of a diet also influences emptying from the stomach. Specifically, studies supplementing the diet with either glucose or fructose for just a few days have shown the emptying of these sugars to be accelerated. The reasons for this adaptation are still being elucidated but almost certainly involve less feedback inhibition from receptors in your small intestine that detect the presence of carbohydrate. This feedback inhibition is a way for your body to regulate the amount of sugar being dumped into your small intestine.

Interestingly, fasting or heavy caloric restriction for several days also slows emptying of carbohydrate from the stomach, and it’s long been known that the dietary restriction typical of anorexia nervosa induces similar delays and that these effects are quickly reversed if adequate nutrition is provided. Slowed stomach emptying might also help to explain why athletes who heavily restrict energy intake experience more gut problems than their well-fed counterparts.

The practical implication of this research is that if you plan to consume large amounts of carbohydrate during competition, make sure you don’t heavily restrict energy intake during the days leading up to competition, particularly from carbohydrate-rich foods and beverages. If you do, emptying of carbohydrate from your stomach might be slowed and could increase the likelihood of symptoms like fullness, reflux, and nausea.

—

Excerpted and adapted from The Athlete’s Gut by Patrick Wilson, with permission from VeloPress.