It doesn’t matter if you ran the mile in college, ran it on your high school track team, or ran it in gym class for the (much-dreaded) physical fitness test. The mile looms large in the psyche of pretty much everyone who has dared to put one foot in front of the other and time ourselves doing it. People in the seat next to you on an airplane might not know that a 2:15 marathon is fast, but they probably recognize the significance of a 5-minute or 4-minute mile. Its length makes it manageable and accessible, but that same accessibility also makes it commonly feared: The mile sucks and most everyone knows it.

So before we get into the gory details of my latest mile attempt at age 38, due to the inadvertent goading from this website and its “Master The Mile” plan, a little bit more about me. I was a high school track and cross-country standout growing up as a kid in Maryland. After graduating, I ran well enough to talk/walk my way onto the team at Penn State — thanks to an old-school coach who had more interest in developing okay kids from the east coast than importing fast kids from elsewhere and making them slightly faster. As the years progressed, I went from a 4:20-something miler in high school to running a 4:01 1600m leg on Penn State’s school-record-setting DMR as a senior. Now to be clear, I considered myself a steeplechaser and not a miler, though I ran the mile pretty well too.

In the years that followed, I left running behind (sort of) and traded my track spikes for cycling shoes and goggles and my baggy cross-country singlet for a one-piece triathlon suit. I raced around the world, swimming, biking, and running for a job until that one day when I was stretching on the floor of my hotel room, looked up at the desk, and noticed the same sticker I had seen at some point in that same room, years before. Groundhog Day had finally descended on me (the Bill Murray movie, not the weather prediction superstition), and the whole thing felt like swimming, biking, and running in circles. Traveling the world as a pro triathlete had lost its novelty, and it was time for The Next Thing.

Without getting into too many (more) details, I spent the next years running when it was convenient, working hard uphill, maybe doing a road race here or there, and coaching high school cross-country and track. I still ran fairly often, and I was in pretty good shape, but if you had put me in a race with one of my top high school guys, I probably would have walked away sheepishly humbled. I still worked hard from time to time, but I hadn’t truly been measured in that old familiar way in a very very long time.

Then, like it came for everyone, the pandemic hit. Now before your eyes glaze over, this isn’t a story about self-discovery during the coronavirus or about how I learned to slow down and appreciate something or whatever. This is not that. This is still about the mile.

At some point in the last two months, I decided it was time for a new next challenge. Thanks to the fateful appearance of Mario Fraoili’s 8-week training plan that seemed to scream at me: Chris, you need to run the mile again!, I decided my newest challenge would also be one of my oldest.

Looking at my calendar, I was going on vacation four weeks from the day I read Mario’s story, so I figured I’d cut the plan down, just a little bit. This was fine, I reasoned, because the plan looked like you hadn’t done any hard workouts at the start, and I had already done a few intervals here and there with my high school kids. Plus, I’m a Former College Runner, so yeah, I could cut a corner here or there and still be awesome.

The initial time trial went well — like really well. I ran in a pair of road racing shoes that had been sent to me for a review. (Oh, did I mention I’m the executive editor over at Triathlete? No matter, carry on.) Out of respect for my old-man body, I decided to pace myself very evenly at the risk of going out hard and dying on the third lap — like almost every overexcited high school freshman has done since the dawn of time. I was running by myself, so it was just a matter of staying controlled and finding a manageable pace. I hit my splits almost dead even at 66s, and without really killing myself, I ended up with 4:26. Not bad for an old man and basically no track training!

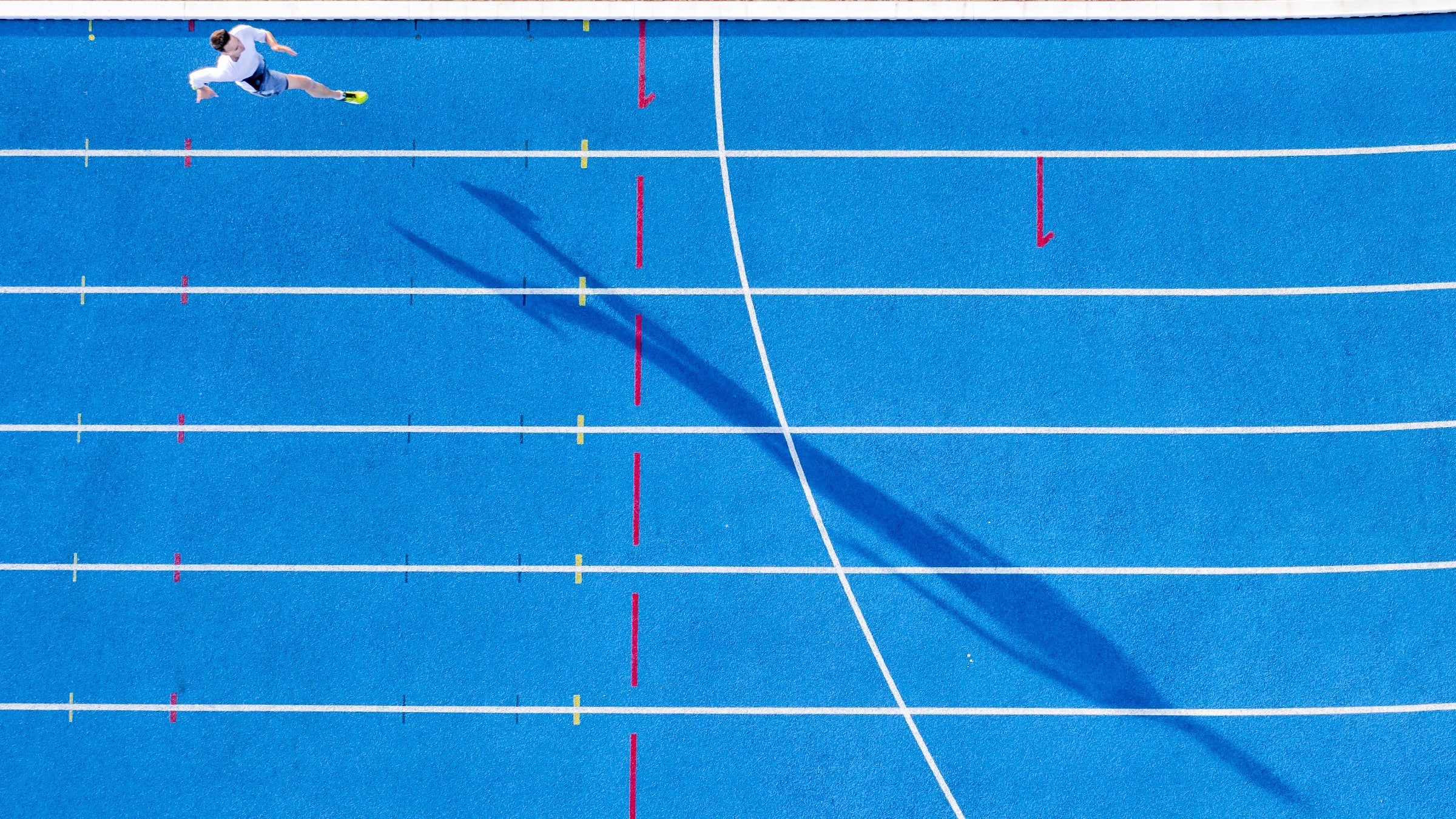

So that was exciting. Knowing that it was still in there, deep down — and though it was a very far cry from my days of 4:0-something, at least I was near High School Chris. Over the next four weeks, I did my track workouts and my hilly runs and all of the hard little things on the training plan. The track workouts oddly didn’t get much easier as I went (“Old School Chris” doesn’t recover as fast as the High School version, I guess), but it was fun doing something pointy and serious on my runs — going out to the track with exact splits to hit and no waffling about “a decent effort” or “just pushing a little bit today.” I had to hit a certain time, and if I didn’t, I didn’t. The track don’t lie.

In fact, I liked to imagine myself as some cool pro runner or college guy home from school, walking onto the track alone, hitting workouts in spikes in the early hours of the day, before everyone else was out of bed. There was a monastic seriousness about the whole endeavor, without any fanfare or Strava kudos. Of course I wasn’t a cool pro runner, a college guy, or a monk, but it was a good feeling nonetheless.

And while each workout seemingly hurt the same or somehow more than the last one, the thought of that pure mile goal carried me through those four weeks. I didn’t have to think about race strategy, nutrition, the course profile, or anything like that. When the day came, I would bring the fitness I had gained over the last four weeks and nothing else.

The day finally came, and I decided to head out to the track early. It was sunny, but not hot, and completely windless — classic mile conditions for sure. I started myself unceremoniously, witnessed by no one but two early-morning joggers in the outside lanes. No gun, no “runners to the line,” I just went over and hit start on my watch.

I pushed the first lap in hopes of hitting my goal time of 4:19. If I could run that, I’d be ecstatic and all of the work would be worth it. The first lap: 64 seconds. It hurt, but not too much. I knew I needed to be slightly under if I was going to hit that time, and a 64 didn’t seem like too much. Second lap: 65 seconds. That one hurt more than I’d hoped — one of those laps where you’re thinking I bet I’m going 63-second pace right now, but nope. Then the third lap happened, just like it does for every high school miler: 67 seconds. Ouch. Suffering.

Things were getting bad and the joggers in the outside lane began to shy away and avoid eye contact with the horror show happening over in lane one. I looked to them for help, but they knew there was nothing they could do for me. This was my fault, and I had no one to blame but myself. The last lap was all arms and feet and shoulders with the legs just along for the ride. My head did all of the things I always tell my high school runners never to do. I slouched; I probably drooled, there was nothing pro or college or monk-like about what I was doing during those last 400 meters. I’d describe my state at that moment using the word “undignified” in a Victorian accent. It was ugly.

The last lap was 67 seconds, and it was literally all I had before almost passing out. I finished with all of that drama and hurt and blood in my mouth in an unsatisfying 4:24. Only two seconds faster than I ran four weeks ago, with substantially more effort and pain. It was disappointing, and educational (hello pacing 101) — but there’s more to it than that.

On my cool-down I realized I had done something special in those four minutes and 24 seconds of hurt. The mile doesn’t care who you are or who you were or what work you’ve done. It’s cruel. It does no favors for friends. But that’s also the true beauty of the mile: It scans an exact black-and-white photocopy of who you are right there — warts and all. You can’t blame nutrition or hills. The course isn’t long or short. On that morning, that’s where I was as a runner. I found my limit that morning, and it was 4:24. And today it’s a rare gift to find where our limits truly are and compare them to where we once were. There’s a satisfaction in that that’s rare, and it was well worth the price of pain.

—

About the Author

Chris Foster is the current executive editor at Triathlete magazine and a former pro ITU/short-course triathlete. After a collegiate running career at Penn State University, where he was a part of the school record-setting distance medley relay with a 4:01 mile leg, Foster represented the U.S. national team at the ITU Elite Triathlon World Championships in 2010.

Today he lives in Los Angeles with his wife where he tends to a small flock of chickens, runs the nearby hills, and swims in the Pacific when it gets a little bit too hot.