Not long after dark on a September Saturday in 1930, a young Navajo boy ran away from the Leupp Boarding School, a Bureau of Indian Affairs institution outside Flagstaff, Arizona. A watchman on horseback spent all night looking for him, crisscrossing 30 miles of desert, but found nothing. The boy’s tracks, discovered the next morning, showed that he had avoided houses and roads and instead ran over slickrock and through soft sand, threading between cactus and sage.

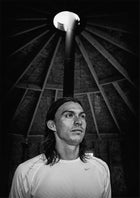

Rolonda Jumbo at home in Chinle.

Rolonda Jumbo at home in Chinle. The start of the 2011 Arizona State Cross Country meet.

The start of the 2011 Arizona State Cross Country meet. Martin, at age four, winning his first running trophy, in 1985.

Martin, at age four, winning his first running trophy, in 1985. Martin in his family’s hogan.

Martin in his family’s hogan.Congressional records about the incident—from subsequent hearings on a host of Native American issues—noted the boy’s age (six) but not his name. They state that he weathered a sandstorm, passed at least one windmill, and at some point decided to lie down between two clumps of greasewood, making him imperceptible from more than a few feet away.

Five days later, his older brother led a search party that found him dead at this spot. He was 35 miles from the school, about halfway to his home near the Navajo reservation town of Indian Wells. The cause of death was listed as exhaustion.

For most of their history, Navajos have run away from school. Though other cases didn’t end as tragically, there were dozens if not hundreds of stories over the years about Navajo kids taking off like this. Beginning in the 1880s, the U.S. government had essentially begun conscripting Native Americans into boarding schools rife with tuberculosis, pinkeye, and other infectious diseases. While some parents and tribal elders resisted the government’s agents, more often they were ignored, threatened, or jailed. It was not unheard of for children to be hog-tied and thrown into truck beds. Principals assigned manual labor and, as part of an overarching mission to strip the students of tradition and culture, forbade them from using the Navajo language.

From the 1870s to the 1950s, fewer than half of all Navajo children attended school. It wasn’t until after World War II—thanks in part to returning Navajo soldiers’ newfound hunger for education and an influx of federal money—that enrollment spiked. Still, there were always students who ran.

In the 1960s, one particularly obstinate adolescent boy fled Leupp several times over the course of two years. He disliked the marching, the bed-making rules, the strict dress code. When he was a toddler, his grandparents had taught him dagha, the Navajo tradition of waking up and running in the dark to greet the sun. He took off at night and ran by moonlight from hilltop to hilltop, watching out for the Navajo police and school officials. He crawled through smoke holes in the roofs of hogans and ate whatever food he could find.

He would run roughly 100 miles over three nights, until he reached his home on the eastern edge of the Grand Canyon. Every time he made it back, his parents fed him a bowl of mutton stew and some fry bread. When the police or a school official showed up looking for him, his parents would always tell him the same thing: “OK, go back.”

We know the name of this boy: Allen Martin. Martin is now 62 and lives in Lechee, Arizona. He remembers that, after his third or fourth escape, school officials got fed up and told his parents they didn’t want him back. He was sent to Milford High School in Utah. He got married after graduating but dropped out of college and ended up working in a coal mine. He often warned his children, “Don’t be like your father. Get educated.”

“WHY ARE YOU HERE? Why am I here?”

It’s August 2011, and Allen Martin’s 31-year-old son, Shaun, has written the word EMBRACE in large black letters on a whiteboard. Martin coaches cross-county and track at the high school in Chinle, Arizona, a small, dusty reservation town near Canyon de Chelly National Monument. Forty-five student athletes look up at him from the black wooden benches of the weight room that serves as his classroom and office.

Martin is a distance runner with a lean build: five foot eleven, 145 pounds. He has long black hair, bronze skin that stretches tightly around almond-shaped eyes, and freckles that he got from his mother, Lisa, who is of German heritage. Martin looks young enough to be a student himself, but he’s conducting this session with well-practiced authority. Beneath EMBRACE he’s drawn a diamond divided into three sections, each with a label: THRESHOLD, LONG RUN, and SPEED. Under the labels are various running terms. To the right, Martin has listed every cross-country meet of the season, with the size of the letters corresponding to the importance of the race.

“It all comes down to one thing,” he says. “One belief that I am very, very passionate about.” The kids follow his eyes. “I want you guys to learn how to become better people who will become successful in life through distance running.” Running, he says, means embracing struggle and pain and learning to overcome. Many of his friends from the reservation did not embrace. Some are in jail. Others are dead.

Martin tells his students about Romero Curley, the first state champion he coached. After Curley graduated in 2007, he had a rough couple of years. His mother, drunk, drove into a ditch and died, then his brother committed suicide. When Curley dropped out of college for the second time, Martin and his wife, Melissa, took him in. A few months later, Curley stole all their native jewelry and clothes and sold them to a pawn shop. When he refused to explain his actions or apologize, Martin told him never to speak to him again.

Curley did not embrace, but many others have. “The focus is Tia Dalton getting the Gates Millennium scholarship,” Martin says, rattling off success stories about last year’s seniors. “The focus is Darrick Joey going to Diné College on a running scholarship. The focus is Charnelle Curley going to Central Arizona College on a scholarship. The focus is Stephanie Yazzie going to the Air Force Academy and having everything paid for.”

Part of Martin’s role is to watch for signs that his students are slipping, owing to outside pressures. If someone doesn’t run well at a meet or appears to be in a funk, he wants to know why. “Is there something going on at home?” he’ll ask. “Is there something going on socially? Jonny, did you just break up with the fifth girl from Tuba City?”

Jonathan Yazzie, a senior and the top male on the team, runs a 4:23 mile and has dreams of competing for the University of Wisconsin, because it’s “far from home.” At local meets he often finishes first, and the girls from nearby Tuba City have noticed. Yazzie looks blankly at Martin as several girls giggle. “Sixth,” the girls offer, their laughter bouncing off the classroom’s cinder-block walls.

“OK,” Martin says, changing the tone. “Now listen.” He tells them they need to live as runners, not like runners. What can they do to achieve this?

Students raise their hands, and he writes on the board: nutrition, sleep, outlook, and a dozen more words. “Is there anything else that should be up there?” Martin says. “There’s one key area that you guys are missing…. Massive area.”

Someone says progression. Martin replies that the diamond is a progressive model. That it’s about growing, about each individual getting better over time, not winning races. What else, he asks.

The students look around and whisper. “Oh,” senior Rolonda Jumbo says softly. Jumbo is a three-time Arizona cross-country champion, a five-time state track champion in distance events, and the student-body president. “Academics.”

THE RECEPTIONIST AT THE Holiday Inn tells me that, aside from tourists headed to Canyon de Chelly, the ancestral home of the Navajo, nothing much blows into Chinle but dust. Worn black tires take on a second life weighing down the sun-bleached roofs of double-wides. Barbed-wire fencing protects derelict pickups in barren yards of sand. Hot summer sunshine scrubs the color out of everything but the graffiti on tribal housing.

Tucked in the northeastern corner of Arizona, the town of 4,500 sits roughly in the middle of the sprawling, 27,000-square-mile Navajo Nation, where the unemployment rate hovers above 40 percent and the median household income is just over $20,000. Life ends early here and often unexpectedly. Accidents, many of them related to drugs and alcohol, are the leading cause of death.

Eight years ago, Martin came to Chinle straight out of college with hopes of building a solid running program at a high school where the graduation rate was only 50 percent and basketball stood so far above every other sport that the town was about to spend $30 million on a 6,000-seat arena, which it built in 2006. The cross-country team had had a decent record before Martin and his wife, Melissa, arrived but hadn’t won a state title since the mid-'90s. During the Martins’ tenure—Melissa coached the girls for two years—the Chinle High School boys and girls teams have finished as state champions or runners-up 12 times. The boys won the 2010 state cross-country title, and the girls won four titles. Perhaps more impressively, Martin has helped 100 percent of his athletes graduate. For the past few years, he has also run Wings for America, a national non-profit that sponsors summer programs to teach top Native American runners about health, fitness, and education.

In Arizona, high schools are categorized according to size, with Division IV the smallest and Division I the largest. Chinle is a Division III school—midsize, but its teams put up collective times that are on par with much larger schools. When I first visit Martin, during the run-up to the 2011–12 season, he’s coaching (in addition to Yazzie) a junior named Searle Tracy who can run a 4:32 mile. His top female runner, Jumbo, is in a position to make history: if she wins state again, she will become the first woman in Arizona to win the individual cross-country title four years in a row. But the real strength of Martin’s team is its depth. Most squads have a few speedy kids and that’s it. Chinle’s roster is fast from top to bottom.

Even more impressive are the team’s college acceptance rates. At a school where only 15 percent of the students continue past high school, the majority of Martin’s seniors over the past two years have earned running scholarships.

Martin and his wife, a fourth grade teacher at the elementary school in town, have two kids of their own: Maverick, 4, and Isabell, 1. Between work and family, he doesn’t have much spare time, but he uses what he has to run. Some days, Martin leaves his apartment before sunup and trains for a few hours. On others he packs water and light gear and takes off for days at a time on reservation trails. He runs on Black Mesa, the massive 8,000-foot plateau just outside town, where he can see the curve of the earth; through the ponderosa pines of the Chuska Mountains, where he passes wild turkeys and bears; and on the goat trail behind the local hospital, where he startles rattlesnakes.

Martin has won several events in the Southwest, including the Red Mountain and Goblin Valley 50Ks and the six-stage, 148-mile Desert Rats race. His goal is to use his tribal traditions to boost his ultramarathon performances and, if he can find the time to ramp up his training, become fast enough that sponsors might take notice.

These days, however, coaching is all-consuming. Every hour he spends helping his kids achieve their goals is one less he can devote to his own. Not long after the season begins, something has to give. Following a long conversation with Billy Mills, the legendary Sioux runner who, at age 26, won gold in the 10,000 meters at the 1964 Olympics, Martin decided to stop moonlighting as the director of Wings. One of Mills’ biggest regrets in life is not running more after he became famous. Martin doesn’t want to have the same feelings about his career as a competitive runner. Many ultra-distance athletes don’t peak until their early forties. There’s still time.

DISTANCE RUNNING HAS ALWAYS been an important part of Navajo life. Before the Spanish brought horses, hunters ran deer to exhaustion. Messengers ran news between camps, scouts searched out new water sources, warriors raided neighboring tribes, and parties gathered salt on multi-day missions to remote mountain lakes.

In the Navajo creation story, a girl named White Shell Woman ran toward the horizon until she became Changing Woman, an eternal being who represents the seasons. Adolescent girls re-create that moment during Kinaalda, a ceremony in which a girl runs as far as she can after getting her first period. The farther she runs, the more successful she will be in life.

Many Navajo children haven’t learned such things, so every season Martin asks his father-in-law, William Yazzie, one of the town’s most respected elders, to recount their creation myth for the team. Yazzie tells the teenagers how, when monsters plagued the Navajo people, Changing Woman gave birth to twins. Through running long distances with holy people, the twins became powerful war gods who vanquished the monsters. “Our young people, especially Shaun’s runners, are like the twins,” Yazzie told me. “They’re training because there are evil things, evil monsters, that are plaguing the people today—alcoholism, drugs, unemployment.”

Martin’s first memory is of running, although it has little to do with tradition. With his mother at his side, he pushed through the pain in his lungs during the final few hundred feet of a Memorial Day 5K race in his hometown of Page, Arizona. After the race, an announcer in the town square called his name as the winner of the youngest-runner award. It was his fourth birthday. He had an epiphany: I can win stuff doing this.

His father, elder twin brothers, and eldest brother also raced, and the family won the award for largest participation. They had had plenty of practice. For years, every morning before the sun came up, Allen Martin walked into the kids’ bedroom, flicked on the lights, and said, “Wake up. Time to run.”

Allen has a build that speaks to his decades of work in the Peabody coal mine, a major reservation employer. He has wide, square shoulders and thick hands crowned with knuckles the size of walnuts. If the boys slept in too late, they sometimes got a walnut to the sternum. Other times, Allen simply went outside, grabbed the hose, opened the window, and sprayed until the boys got moving.

Allen stressed that Navajo teachings were a way of life, not a religion. As they waited for the sun to appear, he taught his children to yell or spit toward the east, to clear their airways of the previous day’s evils. When Shaun and his brothers brought friends over with troubled family situations, his parents let them stay for days and sometimes weeks.

Martin never really stopped running. Even though he lacked the natural abilities of his twin brothers, both of whom were college All-Americans, he won two Division IV titles in high school. He attended Northern Arizona University on a full-ride scholarship. IT-band injuries prevented him from running at his fullest potential, but he graduated in 2004 with a degree in health promotion for education. Shortly after, he and Melissa, whom he started dating during his junior year, moved to Chinle, where she grew up.

TWICE A SUMMER, MARTIN takes his students into the wilderness. In late June last year, I joined him, his family, and about two dozen students and relatives as they camped and ran for four days among the ponderosa pines at Narbona Pass in northwestern New Mexico. High school regulations forbid coaches from providing any formal instruction during the off-season, so Martin didn’t hold mandatory practices. The mood was relaxed, more family camping trip than sports clinic. The kids went on group runs, played cops and robbers, and told running stories around the campfire at night. On the final day, three generations lined up for the Narbona Pass Classic, the gathering’s annual 10K fun run.

A few weeks later, in mid-July, I met up with Martin for another week of running at a campground area near Duck Creek, Utah. This time it wasn’t a family affair: there were just the kids, about half the team, along with Martin and two other adult volunteers. Martin led runs in the morning; during the day, everybody hiked and visited cold springs. In the evenings, the group grilled up fresh fish and green chile for dinner and entertained themselves by playing cards and passing around Sharpies for a tattoo contest. One morning, Martin led the group to a lake at 9,000 feet. He ran up front with Yazzie, chatting the whole way.

Yazzie used to lived with his mother. When his father came over, his parents usually fought, so Yazzie would grab his shoes and take off running to clear his head. A few years ago, his mother moved to Phoenix; Yazzie and his younger brother and sister decided to stay and live with their grandparents. Yazzie tutors his siblings and oversees their chores, and summer camp is a welcome break. While he and Martin knock off nine miles at a six-and-a-half-minute pace, Martin fills his head with talk of grades and scholarships.

It isn’t until August, when running season begins, that I’m finally able to observe Martin truly coaching, making micro-adjustments to a student’s gait when her hips and knees get sore, helping another figure out how to run without getting tight calves. His vigilance extends beyond the track, too. He checks his students’ grades daily and inquires constantly about specific classes and assignments. Mostly, though, he lets his students do the talking.

He arrives at practices early, stays late. At his apartment, he has an open-door policy. Former students routinely drive 40 miles just to use his computer. Over the course of six months, I saw him talk to students about everything from tardiness to rape. “Especially with life on the rez, man,” Martin says, “there’s something drastic happening in family and personal lives all of the time.

“They’re just wanting to talk about what’s bothering them. Who’s doing what? Who’s locked up? Who’s beating whom? All that stuff,” he said. “It’s just another day, but it’s how they’re learning to deal with it through running that’s helping them.”

ON AUGUST 30, THE team bus winds up the hill to Hopi High School, a complex perched atop a mesa and miles from any homes, for the first meet of the season. Martin gathers the athletes under the limited shade offered by aluminum bleachers and tells them the plan. They should push it a bit in the beginning, run “comfortably fast” for the next two-thirds of the race, and pick up the pace near the end, depending on how they feel. The teams warm up as students on passing buses taunt them in Hopi.

When the first race starts, Martin begins darting around like a rabbit. Occasionally, he takes out a small notepad and writes. He doesn’t yell or even speak loudly, which is part of the reason he never stops moving: if he’s amid a section of cheering adults near the start or finish, his runners won’t be able to hear him.

“Are you comfortable?” he asks a freshman junior varsity runner named Tamika. She nods. “Smooth and quick,” he says.

“C’mon, Jelly. Comfortably fast,” he says to senior Anjelica Bedonie, and gives quick, specific advice. “Relax your hands. Don’t stress.” “Comfortably fast,” he tells Tracy. “You know you can run there.”

Jumbo’s dad, Jerrison, watches near the finish, wearing a white cowboy hat, a plaid shirt, and a hamburger-size belt buckle. He tells me that his daughter’s love of rodeo almost ended her running career. While she was riding barrels in the family arena during the spring of her sophomore year, her horse turned too sharply and she sliced her leg against a rusted metal barrel. Martin got a call and went to the hospital. If the metal had hit an inch higher, she would have wrecked her patellar tendon.

Jerrison blamed himself, and now he won’t let her ride, for two reasons. One is that he likes the sensation he feels when she crosses the finish line first. “It makes me feel strong,” he says. The second is more important: “Because we’re looking at a scholarship.” More than a dozen schools have already expressed interest.

Jumbo wins and leads the girls varsity team to victory. Jonathan Yazzie wins and leads the boys team to victory. Both junior varsity teams win. But when I catch up with Martin later, he says he was most impressed by a freshman named Jessica, who finished her first junior varsity race in 15th place. “For her to run that well?” he says. “That shows me she’s a competitor.”

The rest of the season unfolds more or less as Martin scripted it on the whiteboard earlier in the summer. Occasionally, when the teams go to larger, multi-school meets and compete against Division I and II teams, they don’t dominate the podium. But mostly they win. In October, the boys and girls teams sweep the regionals. In November, the state meet finally arrives.

On a warm Saturday, fat cumulus clouds float overhead as Arizona’s top teams race around the manicured greens and man-made ponds of Phoenix’s Cave Creek golf course. Jumbo scorches the field and wins her fourth state title. The boys don’t do as well. Tracy finishes fifth, and Yazzie comes in a disappointing ninth.

When Martin finds Yazzie after the race, he’s on the ground, rubbing his calves.

I bonked, he says.

“It happens,” Martin replies.

The rest of the team does well enough, according to Martin’s quick calculations, to be in contention for the team title. Even so, both team races are initially too close to call. After a few agonizing minutes, during which Martin reminds his team that state titles are beside the point, the announcer finally calls out a Chinle sweep. For the sixth and seventh times in his career, a Martin-coached cross-country team has won a state title.

THE FOLLOWING SPRING, YAZZIE will earn a full ride at Central Arizona University. Jumbo will turn down offers from the University of Colorado and Lipscomb, deciding instead to run for Northern Arizona University, also on a full scholarship. All of Martin’s seniors will earn scholarships, seven for running, one for basketball, and two for academics.

The school year didn’t end as well for Martin, however. In May, he met with Chinle’s athletic director, Steve Troglia, to seek approval to attend more out-of-state meets this year, with the hope of qualifying for more national events. Previous athletic directors had always said yes to Martin’s requests, in part because it was an easy decision: all Martin needed was permission; the team would always raise the money and pay its own way.

But Martin and Troglia’s relationship was more fraught, with Troglia preferring that the team focus its efforts on winning in-state meets and Martin growing increasingly frustrated with the level of support he was receiving. While the exact details of their discussion are fuzzy—Troglia says he initially thought Martin was asking him for more money, not just approval—one thing is certain: Martin had no interest in continuing to plead his case, and the conversation ended with Martin handing over a letter of resignation he’d already typed up. “We’ll still keep getting team titles,” Martin says. “But what’s the point if everything I talk about is progression?”

Martin hadn’t groomed a successor, and the future of the program is now uncertain. The team will likely remain strong for another few years, but without someone to cultivate young runners and keep them on track, Chinle will probably cease to be a powerhouse.

This past summer, there was no team camping at Duck Creek or Narbona Pass. Returning senior Deriann Yazzie said that only four athletes trained consistently, because runs felt empty without Martin. On several occasions, Yazzie seriously considered going to Martin’s apartment to ask him to coach one more year, but she wanted to respect his decision. She trained every day, sometimes twice. Her mother asked her to tone it down. She didn’t listen, because she wants to fulfill Martin’s prediction. “He believes I can get a scholarship in running,” she says.

While many of Martin’s athletes and their parents were shocked at his decision, those closest to him weren’t. The Monday after he quit coaching, Martin signed a sponsorship deal with a small race-management company that pays for his travel to ultrarunning events, with bonuses for high finishes. This past spring, he won and broke his record in both the Shiprock Marathon and Utah’s Red Mountain 50K. In June, he dropped out of the longer 148-mile Desert Rats race because he couldn’t hold down food or water. His goal is to do a race almost every month, building up to bigger ones like the North Face Endurance Challenge, a 50-mile event in December.

The training will be a burden on Melissa, though she would never say so. “It gives him time to think,” she says. “It gives him time to unwind. It gives him time to pray. I know that he thinks a lot about us when he runs. So I’m OK with it. I mean, look at what he does with running. How can you say no to that?”

DURING THE FALL, MELISSA will drive Shaun to the family’s hogan, on the plateau above Canyon de Chelly, so he can run 30 miles through the canyon back to their apartment in Chinle. In the dark, he’ll run amid the scent of juniper and sage and on red clay roads. When the road finally turns east, he will momentarily interrupt the smooth and steady rhythm of his breathing with a traditional two-syllable yell toward the rising sun, a call he has made since he was three: “Haaaaa-weeeee.”

He’ll wind down more than a mile of switchbacked singletrack, past layers of rock cut down by millions of years of rain and snowmelt. If fast-moving clouds cast shadows in his path, he’ll bend over quickly, pick up the dirt, and press it to his chest. The clouds’ occupation is to cover long distances, and he wants their blessing. When he has a signal, he’ll check his GPS watch and note his speed and distance.

He’ll run across streams, under blushing cottonwoods, and through the deep, soft white sand of the Chinle Wash, where 150 years ago, defeated Navajos began a forced march out of their homeland and where four-wheel-drive jeeps now shuttle tourists up the chasm. At the point where the river turns north, he’ll head west and run through the town of barbed wire and dust. He will pray for the ability to move like water. “Always going toward something” is his mantra. “Being smooth and relaxed when the time is right, and, when the time is necessary to be hard and forceful and very powerful, to run like that and to live like that.”

Joe Spring (@JoeSpring) is the writer and associate producer of the documentary Run to the East.