Every workout has a potential risk and also a possible reward. “Risk” refers not only to overtraining but also to injury, illness, mental burnout, and other breakdowns that may occur because a workout or a closely spaced series of workouts is overly challenging. “Reward” has to do with the fitness and performance benefits that result from training. In your training you should seek to balance these two variables.

You can’t have a reward without taking some risk. That’s just the way life is. For example, using these same terms, we could be talking about making investment decisions. You could put your hard-earned money into bonds that have low risk. They also tend to have a small reward, and you cannot expect to become rich overnight by investing this way. Low risk almost always means low reward. On the other hand, you could choose to invest in a start-up company that has great promise in a new field of technology that has vast potential. If the company and the new technology succeed, you could multiply your investment a hundredfold. Then again, if the company fails or the technology doesn’t pan out, you could lose every cent. High risk means a potentially high reward. It’s much the same with training.

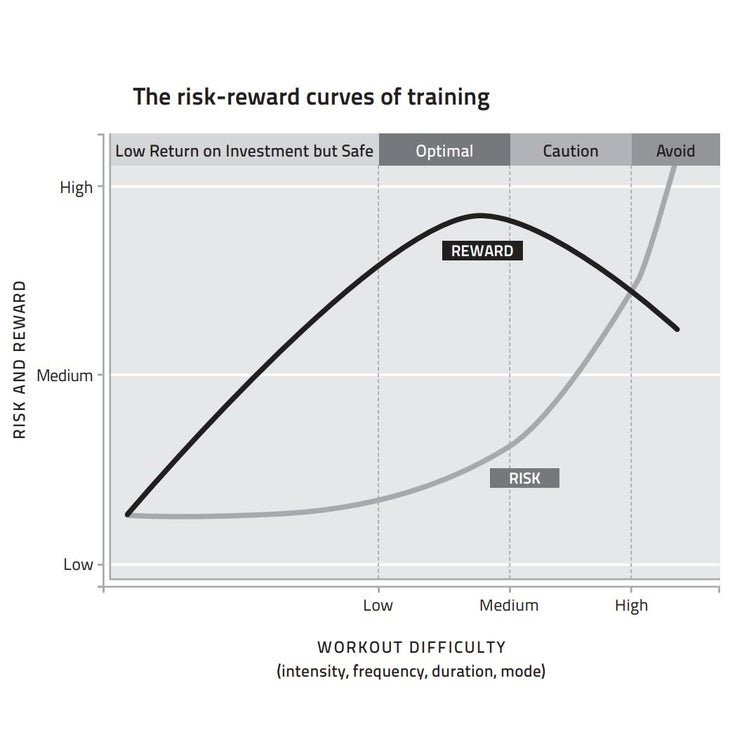

This graph illustrates the risk–reward curves of training. Your goal should be to put in a lot of training in the “optimal” zone, only a little training in the “caution” zone, and none in the “avoid” zone. The “low return but safe” zone is primarily for recovery sessions, aerobic-threshold development, and maintenance. Unfortunately, this latter part is where most of us who are north of age 50 increasingly spend our training time. To avoid training without improvement, we need to put in time in the “optimal” and “caution” zones, which is where high-intensity training fits in.

How do you determine which zone you are in during a workout? Much depends on variables that include your current level of fitness, your sport experience, how well rested you are, your recent diet, and the psychological stress in your life. The proper workload for any workout is based largely on what you know about yourself. As an experienced athlete, you can pair your lifelong response to training with your knowledge of intensity levels, using whichever method you have employed to monitor intensity throughout your athletic career. But if in doubt about how long or hard a high-intensity session should be, err on the low side. As you learn more about such training and how your body responds to it, your workouts will become more refined and will more closely match your needs.

Risk

The riskiest training most commonly involves the possibility of overuse injuries. Running is perhaps the riskiest endurance sport due primarily to the orthopedic stress, or pounding, associated with it. In fact, runners without a history of injuries are rare. Soft but firm running surfaces, such as trails, grass, and dirt, moderate some of the risk of running. But running is inherently risky due to its eccentric muscle contractions, wherein a muscle lengthens as it is trying to shorten. This sounds impossible, but visualize a reverse arm curl in which you slowly lower a heavy weight. As the weight is lowered, the biceps gets longer at the same time that it is trying to shorten to prevent gravity from making the load fall too fast. The strain on the muscle is tremendous. The runner’s calf and quads experience this phenomenon with every step. That’s why a runner’s legs are so sore after a marathon. Essentially, the muscles are being pulled apart.

Cycling, Nordic skiing, rowing, and swimming, on the other hand, rely primarily on concentric contractions, meaning the muscle only gets shorter as it contracts. Visualize your arm curling a heavy weight from hip height to shoulder height. The strain on the muscle is reduced. It’s not being pulled apart, so the risk of injury is lower.

Runners must be extremely cautious with risk in their attempt to reap a reward. Workloads that have a low to moderate risk in other sports may be in the “avoid” zone in running. If you are a runner, you should be especially concerned with training moderation. Should you also have a history of overuse injuries, you must do everything you can to mitigate risk by training with caution and moderation while getting adequate recovery.

Swimming is one of the lowest-risk sports. While overuse injuries certainly occur among swimmers (mostly in the shoulder), the rate of such setbacks is low compared with that of runners. Poor technique and the use of paddles and drag or resistance devices increase the risk for swimmers, as does rapidly increasing the volume and intensity of training.

Cycling is a similar story, although here the knee is the body part most commonly injured from too much training stress. Risk is increased in cycling first and foremost through poor bike setup. The most common bike setups that are high-risk for the knee have the saddle too low and too far forward. These errors are common for novices, but older athletes can fall into the same mistakes when they make adjustments to compensate for limited mobility in the shoulders and neck. Also raising the risk for cyclists is high-gear pedaling, especially on hills in the seated position. Inadequate gearing, meaning not enough low gears, is often associated with knee soreness and loss of training time due to injury.

Another potentially rewarding activity that carries a high degree of risk for athletes in many sports is plyometrics, especially the kind that includes a lot of landings at the end of downward jumps—jumping over objects or off high platforms, for example. Jumping up from the floor to land on a knee-high box has a much lower risk but also a lower reward. Be cautious with plyometrics, and progress at a quite moderate rate.

Lifting weights is also risky, especially when the loads are high and the reps low. As with intervals, the key to managing the risk is progression—how quickly you increase the loads. The key, as always, is to take a moderate approach when doing reps and adding weight. Stay below the risk curve by doing fewer reps than you think are possible—don’t go to “failure” on a set—and be patient about advancing to the next level of training. Be especially cautious with exercises that place great loads on the knees, shoulders, and low back. Injury to these areas is quite common in weight lifters who don’t moderate the risk.

Athletes who continually experience breakdowns because they overinvest in high-risk training will never achieve their potential. Likewise, those who do only low-risk workouts will never come close to their potential. Some risk in training is required to reap a reward. You need to control that risk with moderation to be successful. You are the only one who knows what the risk is and what “moderation” means for you. If you are unsure or don’t trust yourself to make wise decisions in managing risk, you should hire a coach or trainer. Find someone who is experienced in working with senior athletes in your specific sport.

Reward

That’s the risk side of training. How about the rewards? Exactly what positive outcomes can you expect as a result of high-intensity training? There are solid benefits of increased aerobic capacity from doing intervals and greater aerobically active muscle mass as a result of weight lifting. All of those deliver greater performance for athletes. But there’s more to expect from high-intensity training that is especially enticing to senior athletes. This enticement has to do with hormones, those chemicals the body produces in the glands that regulate our health and physiology.

As with most aging conditions, we have some degree of control over our hormones. You can somewhat speed up or slow down your body’s anabolic hormone production based on your lifestyle and training. The hormones involved include testosterone, human growth hormone, and insulin-like growth factor. When these are released into the body by the glands, they stimulate tissue growth and repair. In fact, without them there would be no improvement in fitness and performance.

Another anabolic hormone underproduced with advancing age is erythropoietin (EPO). That’s also the name of a synthetic drug cycling has been dealing with since the early 1990s that was involved with the fall from grace of Lance Armstrong and numerous other athletes. While synthetic EPO is to be avoided, erythropoietin is produced normally by the body and controls red-blood-cell production. Interestingly, it’s also associated with memory. And, perhaps more importantly, it is related to your aerobic capacity. Less naturally occurring EPO means fewer red blood cells, resulting in less oxygen being transported to the muscles and therefore a reduced aerobic capacity.

Unfortunately, all anabolic hormone production, including EPO, greatly diminishes with age. This accounts for much of the physiological change that’s taking place in our sports performance north of 50. But here’s the good news: High-intensity training stimulates anabolic hormone secretion more than does low-intensity, steady-state training. Heavy-load strength training has a similar effect. Following such workouts, hormonal secretion also remains high during the extended recovery period. The results of studies using both older and younger subjects and females as well as males found similar benefits across the board.

Hormone secretion is especially high when you are asleep, the key being the consistency of sleep over time rather than the duration of your snoozing. Just as with the average intensity of your workouts, getting to bed at a regular time appears to be important for natural hormone production. Irregular sleep patterns and a steady diet of only long, slow distance year after year while avoiding the weight room is likely to result in a significant and steady decline in hormonal activity and therefore fitness-related performance. If you’re like most older athletes, sleep isn’t the problem; training intensity is.

The latter point is why I encourage you to do some of your training near your aerobic capacity with intervals while also lifting heavy weights. Both of these must be done regularly and consistently if you are to reap the hormonal rewards. There is no doubt that such training can be risky, so you must be conservative when starting this sort of training and cautious with increasing the workloads. I can’t emphasize enough how critical this is. Always think in terms of moderation as you train in order to minimize risk. Be patient. No injuries. No overtraining.

Adapted from Fast After 50 by Joe Friel with permission of VeloPress.

https://www.velopress.com/books/fast-after-50/