If you buy through our links, we may earn an affiliate commission. This supports our mission to get more people active and outside.Learn about Outside Online's affiliate link policy

New Evidence That Long, Slow Distance Is the Key to Endurance Success

(Photo: AzmanL/Getty)

The logical response to a bad race is simple: train harder. Whatever you’ve been doing didn’t get you the results you wanted, so you need to dial up the intensity to salvage your racing season. Pain is just weakness leaving the body, and you’ve been weak.

As seductive as this logic is, the data in a new study in the International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance suggests that it’s wrong. Sports scientists in the Netherlands analyzed training and racing data from a professional cycling team on the women’s World Tour, trying to pick out the training patterns associated with “highly successful” and “less successful” racing seasons for individual riders. The key to success, it appeared, wasn’t more hard riding—it was more easy riding, a conclusion that dovetails with some of the biggest trends in endurance training.

The study was led by Annemiek Roete and Robert Lamberts of the University of Groningen, and included data from 14 cyclists over a total of 43 seasons between 2013 and 2019. In 18 of those seasons, the riders averaged at least 5 points per race, according to the website ProCyclingStats, which roughly corresponds to being in the top 15 percent the peloton. These seasons were labeled “highly successful,” while the other 25 seasons were labeled “less successful.”

The researchers had access to comprehensive training data from those seasons: how long and far the cyclists rode, their power output, heart rate, perceived exertion, and more. From this data, the amount of time they spent in various intensity zones (calculated based on either power output or heart rate) could be calculated.

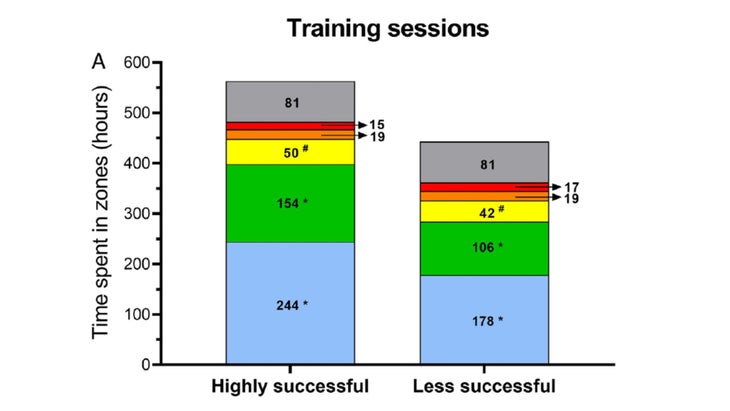

Here’s the key data, showing how much time the riders spend in six zones of power output over the course of the full training season:

The most obvious difference is that the cyclists trained more during the highly successful seasons, racking up a total of 563 hours compared to 443 hours in less successful seasons. Their average rides were both longer (2.6 vs. 2.3 hours) and farther (47 vs. 42 miles), but the average power was basically the same (130 vs. 131 watts).

Where did all this extra training happen? In zones 1 and 2, which correspond to less than 55 and less than 75 percent of functional threshold power, a threshold concept that’s widely used in cycling and corresponds to the average power you could sustain for an hour. In other words, the riders did more easy riding in their best seasons, but roughly the same amount of harder riding. This fits nicely with the longstanding idea of polarized training, which is sometimes summed up with the rule of thumb that 80 percent of your training should be relatively easy and just 20 percent hard. You could argue that it also fits with the more recent popularity of Norwegian threshold training, which also tends to avoid the upper intensity zones.

The heart rate data backs up this interpretation. During highly successful seasons, the riders averaged 126 beats per minute, or 64 percent of max. In the less successful seasons, it was 132, or 67 percent of max. This is consistent with the idea that the riders were racking up more easy riding, and thus bringing their overall average heart rate down, during the better seasons.

Taken together, these findings echo an analysis I wrote about last year of a very different dataset. Researchers crunched 16 weeks of Strava data from 120,000 runners leading up to marathons that they ran in anywhere from sub-2:30 to 6:30. This encompasses widely varying populations of runners, but the key difference was the same as in Roete and Lamberts’s data: the faster marathoners did significantly more easy running than the slower runners, but similar amounts of medium and hard running.

One problem with the marathon data is that you don’t know which direction the arrow of causality is pointing. Does more slow training make you faster? Or do fast runners have an easier time accumulating more slow training? The cycling data is a little stronger because it includes an average of three seasons from each cyclist, so it suggests that the same cyclist gets faster when they do more easy training.

So does this mean that, instead of hammering your next workout, the best response to a bad race is to start racking up more easy miles? I’d be cautious about jumping in too enthusiastically. Even easy miles put stress on your body, so any changes in training should be gradual and titrated according to your ability to recover between workouts. But in the long term, evidence is mounting that the shift away from gut-busting hero workouts and towards what used to be called LSD—that’s long, slow distance—is a smart one.

For more Sweat Science, join me on Threads and Facebook, sign up for the email newsletter, and check out my new book The Explorer’s Gene: Why We Seek Big Challenges, New Flavors, and the Blank Spots on the Map.