Why Science Says to Pick the Running Shoe That Feels Most Comfortable

(Photo: Canva)

In the current supershoe era, we hear a lot about which running shoes might make you a percent or two (or three) faster when you race. In practice, though, most runners are less interested in marginal speed gains than in whether their shoes will raise or lower their injury risk. This is a tricky and much-debated question, but a new analysis in the European Journal of Sport Science suggests that the key to lowering your injury risk might be as simple as choosing a shoe that feels comfortable—an idea known as the “comfort filter” paradigm.

Do Shoes Even Matter?

Modern running shoes emerged in the 1970s and 1980s, as companies added features like cushioned midsoles, raised heels, and pronation control. It’s hard to get good statistics, or even to compare the very different running populations of the 1970s and the 2000s, but by the time Chris McDougall’s book Born to Run came along in 2009, it was clear that shoe technology hadn’t made shin splints and stress fractures and other running injuries disappear.

There are a few different ways of making sense of this. You could argue that modern shoes really do help, but their benefits are hard to discern because today’s runners are generally more injury-prone than their comparatively hardcore predecessors from the 1970s. You could argue, as McDougall does, that modern running shoes actually cause injuries. Or you could conclude that, in the absence of better research that changes one variable at a time and monitors injury rates, we just don’t know.

A scientist named Laurent Malisoux, based at the Luxembourg Institute of Health, has championed the latter view over the past decade. He has partnered with Decathlon, the French sporting goods giant, to conduct a series of placebo-controlled running injury studies. Decathlon specially manufactures shoes for him that are identical except for one key trait—heel-toe drop, say—and then Malisoux randomly assigns them to runners and monitors their injury rates.

The overall gist of Malisoux’s research is that shoe features do make a difference, but not as clear a one as you might expect. The results sometimes vary depending on the characteristics of the runner. Heel-toe drop didn’t make a difference to injury rates overall, for example, but low-drop shoes seemed to cause more injuries in the subgroup of experienced runners. Pronation control features had a small protective effect in most runners, but a large one in those whose feet tended to roll inwards. The effect of shoe cushioning (which I wrote about here) depended on how much the runners weighed.

Why Comfort May Be the Key

Malisoux’s results don’t make it easy to figure out which shoe you should buy. What if you’re a light, inexperienced runner with feet that pronate inward? Which of these characteristics should determine what shoe to buy?

In 2015, University of Calgary biomechanics researcher Benno Nigg and his colleagues proposed a simpler alternative that they called the “comfort filter.” The idea is that everybody’s unique body and physical history predispose them to move in a characteristic way. If something—a shoe, say—forces you to move in a way that’s unnatural for your body, it will feel uncomfortable and will also place extra stress on your joints and tissues, raising your injury risk. The implication of this idea is that if you try running in several different pairs of shoes, the one that feels most comfortable to you will likely minimize your risk of injury.

This is an intuitively plausible and reassuringly simple idea, and it has been widely adopted by people in the running industry. It’s what I tell my friends if they ask for advice about which shoes to buy. But it hasn’t actually been tested empirically in any rigorous way.

What the New Study Says

To address this gap, Malisoux just published a reanalysis of the data from his 2020 shoe cushioning study. That study involved giving more than 800 runners shoes with either more- or less-cushioned midsoles, with the overall finding that the softer shoes produced fewer injuries among lighter runners over the next six months.

During the study, Malisoux asked the subjects to rate on a scale from 1 to 9 how cushioned the shoes felt to them. He also asked them how cushioned they would like the shoes to be, on the same scale. If the comfort filter is correct, then what matters is how closely those two numbers align: if your perception of how cushioned the shoe is matches how cushioned you want the shoe to be, then you should be less likely to get injured.

To cut to the chase, that’s pretty much what the study found. Not all subjects completed the comfort questionnaire, so in the end there was data from 527 runners. The key variable was “perceived-ideal cushioning difference.” If you thought the shoes felt like they had a cushioning level of 4 on the scale of 1 to 9, and you ideally like shoes that feel like a 6, then your perceived-ideal cushioning difference is negative 2 (4 minus 6).

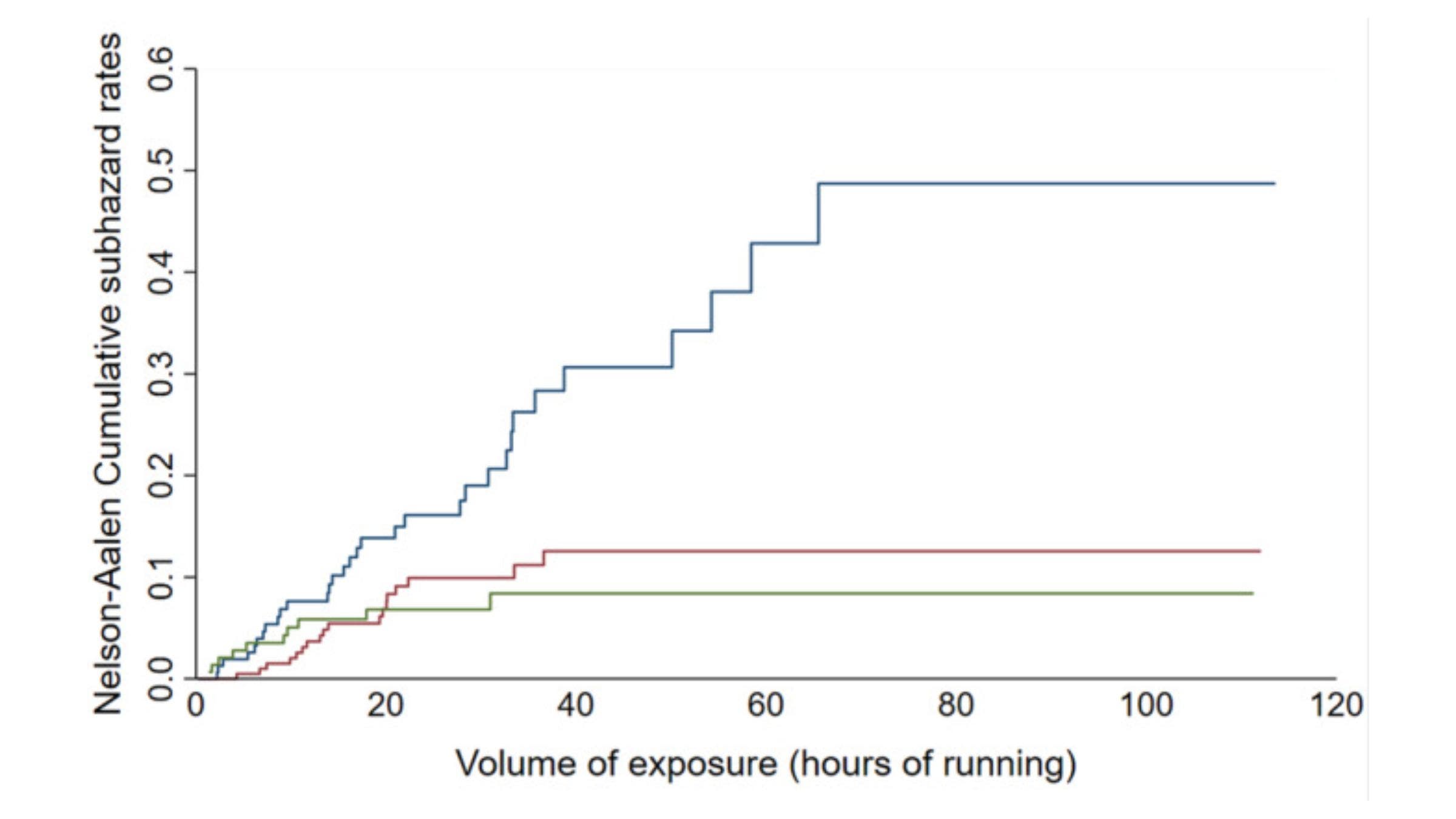

Malisoux split the group into three tertiles, which we’ll call the good match (perceived-ideal cushioning difference of greater than 0), medium match (-2 to 0), and bad match (below -2). Here’s the probability of getting injured for each group as a function of hours of running, with the good match in green, the medium match in red, and the bad match in blue:

Overall, compared to the bad match group, the good match group was 67 percent less likely to get injured during the study, and the medium group was 56 percent less. There wasn’t any significant difference between the medium and good groups, which isn’t surprising because they both border the optimal mismatch value of 0.

The Takeaway

The are a lot of caveats to this study, which Malisoux goes through in detail (the full text is available to read here). The most significant, in my view, is that we can’t really distinguish between two possibilities: that more cushioning is good, or that minimizing the mismatch between perceived and desired cushioning is good. In general, it seems that most of the runners wished they had more cushioning. But it would have been nice to see a breakdown of the small subset of runners who thought their shoes were far too cushioned (i.e. a mismatch value well above 0). Were they also more likely to get injured, or was it just runners who didn’t get enough cushioning who were at risk?

There’s also a distinction between cushioning and overall comfort. The former is a big part of the latter, but it’s not the whole thing. Fit makes a big difference to comfort, as do factors like how narrow or wide the shoe is, or how roomy the toe box is. Do these factors also matter for injury? Malisoux did ask the subjects how much they liked the shoes overall, but this rating mostly tracked with their comfort mismatch ratings.

I could go on about the caveats, but you get the point: the comfort filter still isn’t “proven.” That said, neither is any other approach to picking running shoes. It remains a black art, or at least a murky gray one. So if my friends ask, I’ll keep telling them to pick the shoe that feels best.

For more Sweat Science, sign up for the email newsletter and check out my new book The Explorer’s Gene: Why We Seek Big Challenges, New Flavors, and the Blank Spots on the Map.