If you buy through our links, we may earn an affiliate commission. This supports our mission to get more people active and outside.Learn about Outside Online's affiliate link policy

Does Poor Sleep Lead to Injuries?

(Photo: lzf / iStock / Getty)

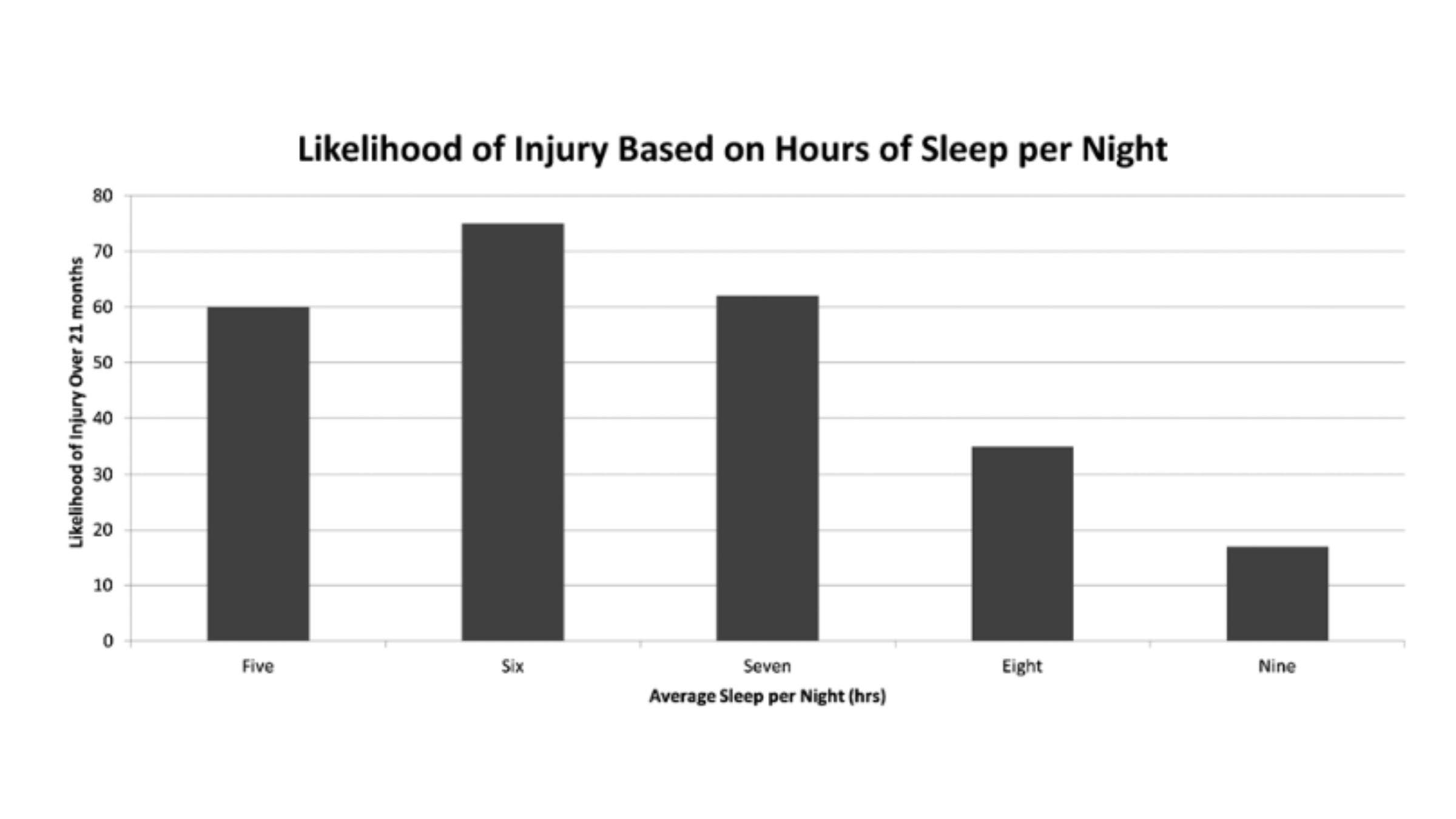

A decade ago, I wrote about a study in the Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics that linked the sleeping habits of a group of Los Angeles-area high-school athletes to how likely they were to get injured. The study included this eyebrow-raising graph:

The graph, which seems to show that getting more sleep protects you from injuries, became semi-famous when it was included in Matthew Walker’s 2017 bestseller Why We Sleep. Walker was criticized for cropping out the bar on the far left (corresponding to five hours of sleep) to make it look as though the relationship between sleep and injury rate was simpler and stronger than the full data showed.

Still, the idea makes intuitive sense. Lack of sleep might mess with the hormonal signals that help your body recover from training, or it might be a symptom of risky overtraining, or it might simply flag that you’re not taking care of your body appropriately. One way or another, it could be a useful sign to warn of impending injury. But in the years since that initial study, the evidence from subsequent research has remained mixed at best.

What the Latest Data Says About Sleep and Injury Risk

All this uncertainty makes a new study from researchers in France, led by Benoit Pairot de Fontenay and Ursula Debarnot of the Université Claude Bernard Lyon, particularly interesting. The researchers ran an online survey asking runners to track their training and injury status every week for 26 weeks, while also filling out a weekly questionnaire about the quality and quantity of their sleep.

The results, which appear in the Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, include data from a total of 339 runners, of whom 43 percent reported at least one injury.

There are two ways of parsing these results. One is an “interindividual” analysis, comparing the runners to each other. Those who reported poorer sleep on average (in response to the question “How was your sleep last night?”, on a scale of 1 to 6) were significantly more likely to subsequently get injured. In fact, for every one-point decrease in sleep quality, they were 36 percent more likely to report an injury. Other questions, including how long they slept and how long it took them to fall asleep, didn’t predict injury.

The other analysis was “intraindividual,” assessing how each runner’s personal risk varied over the course of the study depending on how they slept. They zeroed in on reported injuries to see whether sleep scores from the preceding two weeks gave any hint of the impending disaster.

With this approach, there was no link between sleep and injuries: the scores for sleep quality and quantity were roughly the same one week and two weeks before an injury as they were before weeks with no injury. Instead, the best predictors of impending injury were fatigue (in response to the general question “How fatigued are you?”) and muscle soreness (“Rate your level of muscle soreness”).

The Takeaway

There’s a fundamental problem with trying to predict injuries, which is that they’re always a function of probability. There’s no threshold of sleep deprivation (or hamstring weakness or biomechanical asymmetry or whatever) that guarantees that you’re about to get hurt. Instead, most overuse injuries emerge from a swirling mix of risk factors and warning signs and fluke missteps.

This means that even if lack of sleep plays a genuine role in increasing your injury risk, studies like this will have a hard time proving it. On that narrow question, I’d say the jury is still out. But the study still has some useful insights for us, and the most important is that injuries don’t come out of nowhere. There are warning signs—indicators that, all too often, we acknowledge only in retrospect, after injury has already struck. Once you’re injured, you remember that your legs had been feeling heavy for a week or two; your calves had felt stiff in the mornings; you hadn’t been sleeping well.

The data in the new study validates these premonitions. The fact that the results are a little muddled—one analysis points the finger at sleep quality, the other at fatigue and soreness—simply reinforces the fact that it’s not an exact science. You never know when an injury is coming, and you can’t dial back your training every time you feel tired or sore or sleepy, or you would never train at all. But on some level, you do know when the risk is mounting. You can feel it in your legs, and perhaps sense it when you’re lying awake in the middle of the night, staring at the ceiling. You should pay attention to these warnings and proceed with caution.

For more Sweat Science, sign up for the email newsletter and check out my new book The Explorer’s Gene: Why We Seek Big Challenges, New Flavors, and the Blank Spots on the Map.