On the morning of October 30, 2012, surfer Scott Stephens paddled out to a local break near Eureka, California, and was attacked by a great white shark. Here’s his story, with analysis of the attack, by international shark attack expert George Burgess, as told to former Outside editor Joe Spring.

Before the Great White Shark Attack: A Morning Like Any Other

I’m 25 years old and I live in Samoa, California, which is just outside of Eureka. On October 30, I went down to the beach about 10:00 a.m. It’s only about 10 minutes from my house. It’s BLM land, so you can drive right out on the sand and park. It was just a beautiful morning—really calm offshore winds, a really high tide, and real clean, six-foot waves. I drove down to the beach and just watched for half an hour, figuring where I wanted to go out. There were about 20 guys in the water at a spot called Bunkers, which breaks just north of the jetty that is the harbor entrance to Humboldt Bay. My buddy called me and said, “How do the waves look?”

I said, “How do you know I’m checking the surf right now?”

He said, “I know you too well. I’ll meet you out there.” And so I went out.

I put on my new Xcel 5-4 wetsuit, which I had worn—maybe—a handful of times. I ran along the jetty and jumped in, letting the current take me out. I didn’t really have to paddle too much. It was about a quarter-mile to Bunkers. The wave breaks in pretty deep water about 500 yards from shore. It’s probably one of the furthest out spots that I surf. The waves just seem to funnel in through that channel and then break on the sandbar—A-frames that go right and left.

I went inside most of the guys out there because I’m a shorter guy and I ride a little bit shorter board. I sat where the waves were going to break right on me. I went both right and left, but toward the end, I just went left. I caught three in a row, and that put me further down the beach. I was separated from everyone else by about 150 yards. By that time there was about 10 people left. I had been surfing for more than an hour and a half.

The Attack

I had just caught a wave in and it took me pretty far inside. I remember having a pretty easy time getting back out because I was in a channel. I just wanted another wave. I thought, Maybe I’ll catch a couple more and go in. I paddled all the way back to the outside. Everyone else was inside. I saw a black shape out of the corner of my left eye. Then I just felt a weight land on my back. I thought it was a seal. That was the first thing that went through my head: Oh shit, a seal just jumped out of the water on top of me. I’d seen seals in the water before.

Pretty quickly I changed my mind, because I was dragged under. I was about two feet below the surface when I opened my eyes. That was the first time I’ve seen a shark in the water in 15 years of surfing. It had my left torso and I was staring right into its eyes for a second. It was like we had a connection. It had a huge eye and teeth, which were just so snaggled, almost like it was smiling. I estimated it was about four feet from the tip of the nose to the dorsal fin. I felt one really violent shake as the shark moved its head side to side, like a dog with a toy. I was able to torque my body and punch it behind its right eye. It immediately let me go and swam down and toward shore. The whole thing was just a matter of seconds, but it felt a lot longer than that.

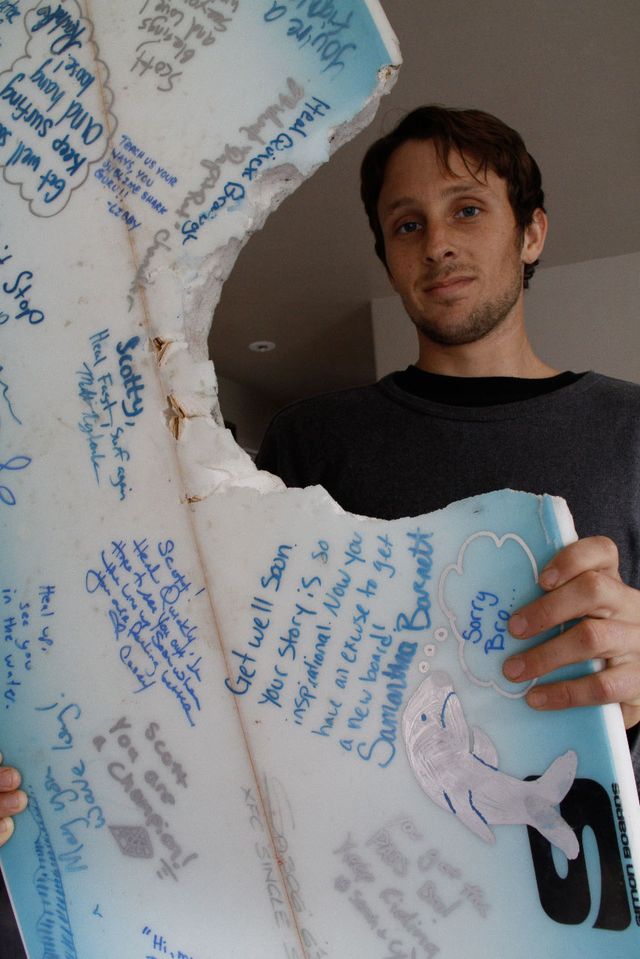

There was no pain. I didn’t have any awareness that I was injured until I got back to my surfboard with the bite mark on it, which was floating five feet away. The board had come out from underneath me when the shark dragged me under. The bottom teeth went clean through it. Based on the 14-inch diameter bite in the board, shark researchers said it was a 10- to11-foot great white. The leash was severed too.

Racing to Shore

I was about 400 yards out. I got on the board and started paddling back to shore. Then I lightly felt back to the area. I thought my whole side was gone. There was a big crimson puddle around me, just blood mixed with water. At that point, I knew I’d been injured, but there still wasn’t that much pain. I was in shock.

I paddled, screamed for help, paddled, screamed for help, paddled, paddled. I definitely had never paddled that fast in my life. I knew I was losing a lot of blood, and I wasn’t sure how much I could lose. I just knew I had to get to shore as soon as I could. When I was about 100 yards from shore, a wave broke and I caught the whitewater and just rode it on my stomach into the beach. Raight as I got into the sand another surfer riding the same wave met me at the beach. He grabbed my surfboard. I told him, “A shark just bit me. I need to go to the hospital. Take me to the hospital right away.”

Emergency Responders Step Up

He went looking for a truck. By that point, there were a couple other surfers on the beach. One had taken EMT classes. His name was Ian Louth. I was on the beach with my injured side up. He immediately lay down on top of me, using his bodyweight to stop the bleeding. Another surfer, Gabes, was driving home on the beach. He picked me up and threw me on the back seat in the back of the king cab. Ian stayed with me the whole time, put the towel on my side, and kept the pressure on. He said, “As long as you’re feeling pain that’s a good sign. You’re going to make it.”

He was trying to keep me calm. Gabes called 911. Gabes drove like a maniac, at about 100mph. An ambulance was able to intercept us a couple miles from the hospital. When they got me into the back, they put an IV on and got some blood back in me. We made it to the ER in about 25 minutes. By the time I got to the hospital I had started clotting, and the bleeding had mostly stopped.

I was in the ER for about 20 minutes. They cut off my wetsuit, gave me oxygen, and said, “We’re going to take you into surgery. Is there anyone you want us to call?”

“OK, you can call my sister,” I said.

“Do you want us to call your parents?”

“Probably better to wait on that,” I said.

They were about to wheel me into surgery when my sister came in. I saw her for a second. My last words before I went under were, “Good luck telling mom.”

The Aftermath: Injuries

I was in surgery for about an hour and a half. The surgeon said the seven- to 12-inch incision marks along my side were so sharp that the teeth had almost functioned like a scalpel. It was almost like a series of surgical cuts, and because they were so clean, the skin went together easily. One of the news reports said my guts were hanging out. The surgeon took a picture just before I went in, and it does kind of look like my guts were hanging out, but it was only my muscle tissue released out through the wound. They stitched up the inside and put staples on the outside. I’ve got about seven foot-long incisions that run from my lower hip up to my armpit, and that was just from

the top teeth scraping down on my side.

I was lucky. The bite marks didn’t hit any arteries or puncture a lung. They just cut through fat, muscle tissue, and skin. The surgeon said the two main factors in my survival were, one, Louth was able to put so much pressure on my wound, and two, that I got there so quick. He also said it was fortunate I was so cold, almost hypothermic. Having a low body temperature helps with the blood clotting. Being young and in good physical condition also helped.

The surgeon told me six weeks until I would be about 90 percent, and a year until I’m 100 percent. A lot of their concern is infection, because sharks don’t brush their teeth, and they eat a lot of trash. I was out of the hospital after a week and getting antibiotic shots every day. I’m still recovering. It severed a lot of the muscle tissue around my hip. I’m struggling with that, but I started swimming about two weeks after I got out of the hospital. Exactly four weeks after I was attacked, I went back out, about two miles from the bite spot. The waves were breaking close to shore and it was sunny. There were quite a few people out.

Return to Surfing

To get back in the water felt pretty good. I’m surprised that I felt so comfortable. Once I started catching waves again, my mind went from thinking about sharks to catching more waves. A few days ago, I went out again to the jetty where I got attacked. That was a little more stressful. I got out there and I was sitting for a minute or two when I saw a fin pop up. It was a porpoise. This porpoise just kind of swam back and forth between me and the outside water, like a guardian.

I surfed for about an hour. A buddy that was on the beach the day I got attacked paddled out and said, “Huddle for safety.”

That’s the thing: the support has been so amazing from the local surf community. The Surfrider chapter here raised $1,700 for my medical bills. The movie theater had a night. The phone calls…. The local brewery had me in for lunch and gave me a bunch of beer. The local surf shop in Arcata gave me a new surfboard. The list goes on and on of people that supported me and said, “Get back in the water when you can, we’re here if you need anything.”

Expert Analysis

Scott Stephens’ close encounter of the shark-y kind is typical of incidents involving white sharks. White shark attacks generally occur from below and behind, where surprise is optimized. Scott’s demographic as a young, white male surfer also is pretty much standard as this represents the dominant aquatic user group in white shark territory. Of particular interest to science (and of even greater consequence to Scott, no doubt) was the success of his aggressive fight-back approach. For many years we have recommended such action because sharks frequently respond to aggressive reaction. I am delighted to see it achieved its desired result. Getting the heck out of Dodge certainly was the correct step two. Whites frequently grab their prey and run, then let go of the food item, only to come back after the prey has apparently been weakened by blood loss. Interestingly, most humans attacked by whites survive, suggesting that our brains usually trump their brawn. Of course, white shark attacks are far less common than those involving smaller shark species, which generally result in lesser trauma. —George Burgess of the International Shark Attack File