When I went to work for Hunter Thompson in June 2003, I was 22, just graduated from NYU, and had met him and his then-fiancée at a party at The Paris Review, where I interned. Shortly after I arrived at his house in Woody Creek, Colorado, a crazed fan showed up in the yard, saying he had a gun and wanted to meet his god. He was around 20 and, we found out later, schizophrenic. Hunter was in the kitchen, shaken up, talking about getting his own gun. I thought he was overreacting, but in retrospect the fear seems reasonable. Hunter’s wife, Anita, a sunny and generous blonde closer to my age than Hunter’s 65, calmed him down, and the three of us sat there until Woody Creek’s sheriff, Bob Braudis, Hunter’s friend for more than 30 years, came out and made the arrest.

Hunter S. Thompson

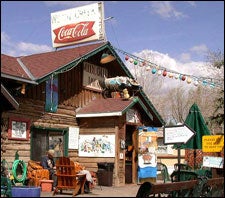

Woody Creek Tavern, one of Thompson's favorite haunts

Woody Creek Tavern, one of Thompson's favorite hauntsMy job description was vague. Hunter had called it “editorial assistant” and talked about books and movies, but other things took precedent. I poached eggs. I poured Chivas. I ordered Chivas. I took notes on meetings with lawyers in the middle of the night. (Hunter was totally nocturnal.) I listened to a conversation with Johnny Depp. When Hunter described the situation with the fan at Owl Farm (not the highly fortified compound portrayed by reporters but an ordinary two-story house eight miles downvalley from Aspen), Depp said he was glad he wasn’t there. They both laughed. Depp had lived in Hunter’s basement in 1997, learning Hunter’s mannerisms for the Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas movie.

I spent most of my time in the kitchen, the house’s command center. Taped to the fridge was

The typewriter was on the countertop. When it was turned on, it got Hunter’s full attention. To the left of his makeshift desk were the books he’d written. He handed them to me often to read aloud. He would yell “God damn!” and clap during parts that excited him. Sometimes hearing his own work built his confidence; sometimes he wondered if he was the author. When I read to him from Hell’s Angels, he kept saying, “This is tough to compete with.” One night, he had me connect the video camera to the TV so he could watch himself.

I washed convertibles. I picked up food from the Woody Creek Tavern. I picked up food from the tavern with Sean Penn, whom, by August, I envied a little because he got to leave when he liked. During one visit, I walked into the middle of a ridiculous story he was telling Hunter about a fight with his first wife, Madonna, involving hair pulling and cops and weeping. When we went down to the tavern, Penn reached across the backseat.

“You can sit back here with me,” he said. Later that night, I remember Hunter saying my age out loud and both of them staring into space. Penn stayed late, but Hunter wasn’t up for it. I think Penn was trying to cheer him up.

That summer, Hunter was recuperating from back surgery to cure his chronic pain. I visited him in the hospital, drove him to physical therapy, and kept him company at the Jerome Bar. Hunter hated the hospital and getting old. There was a sign on his lamp: WHERE WERE YOU WHEN THE FUN STOPPED? Once, when we were driving back from physical therapy, he had me pull off the road near the airport. “I used to come out here when I first moved to Aspen,” he said, “and watch the planes to know I could get out.”

I watered flowers, I fed peacocks. There was a runt peacock, and Hunter could hear it squealing from the kitchen. He said something once about wringing its neck. A lot of dire comments around this time were followed by a spoken “ha-ha-ha.” Bush depressed him; politics depressed him. He told me how embarrassed he was that his generation left this for mine. An assortment of Aspen folk visited, Ed Bradley and Don Johnson. So did his brother Davison, from Kentucky, where Hunter grew up. We shot guns in the backyard. A woman who’d assisted Hunter ten years earlier spent one night talking with him about her work in labor rights. And, yes, the party went on. And, no, it was not always pretty. A few weeks before he died, Hunter wondered aloud how his life might have been without drugs. He said he wouldn’t recommend drugs as a lifestyle but that they’d worked for him.

Hunter wanted to write, and he tried. Sometimes he filed the weekly column on sports and politics that he wrote for ESPN.com. More often he didn’t. Then he was mad, scared, and unpleasant. He hurled insults and, once or twice, objects; often he apologized within moments. He was on edge for weeks at a time. Music helped. The chorus of a song he loved went, “Sometimes I think it’s a shame when I get feeling better, when I’m feeling no pain.”

I was supposed to work for three months but stayed an extra two and left when Hunter’s health started improving in October. Last January, he called in the middle of the night and thanked me. Then he asked if I would come out to work again. I told him no, but that I’d like to come for a weekend next summer.

A few weeks later, I was in a blizzard, stuck in the lobby of an upstateNew York hotel without enough money to pay for a room, when the person sitting next to me got a call. After he hung up, he said Hunter had shot himself.