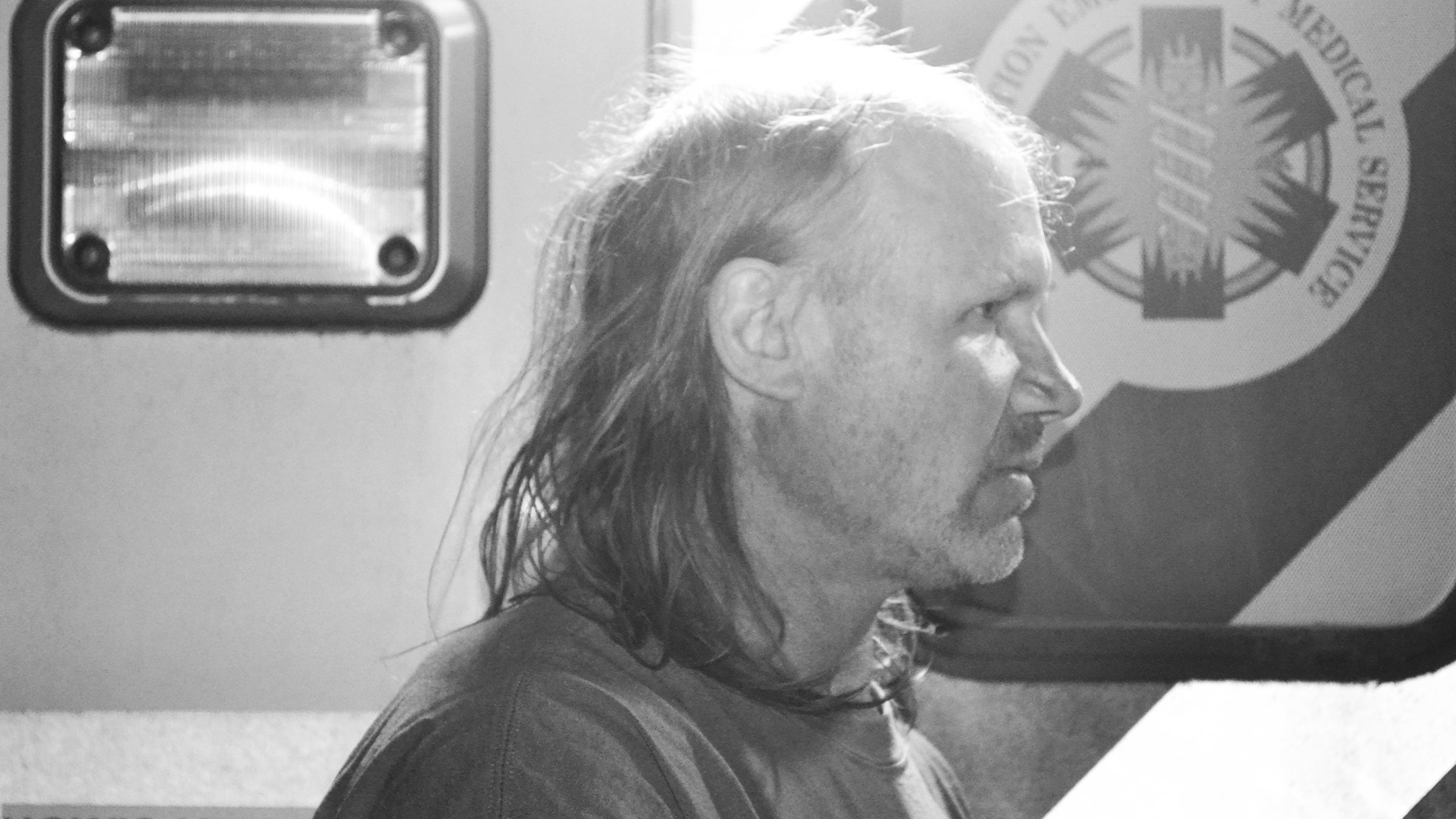

The Final Descent of Dean Cummings

Dean Cummings carving the lower ramp on the Hammer in Alaska’s Chugach Mountains

Early November 2018, Wolf Creek Pass, Colorado

Davey Pitcher watched the shiny yellow sports car roll through the parking lot and pull up just below his office window at Wolf Creek Ski Area, a small operation in southern Colorado that Pitcher runs. A man with a square jaw and muscular build got out. Pitcher immediately recognized legendary big-mountain skier and heli-ski guide Dean Cummings, his friend of 30 years. The car was packed, like it was being lived in. Cummings walked up the stairs to Pitcher’s office, as he did almost every fall when he came to ski early-season powder.

The ski area wasn’t open yet, but the U.S. Freestyle Moguls Team was training near the summit. Pitcher figured that Cummings, who launched his career with the team in 1991, would be eager to ski with them.

Cummings sat down across from Pitcher’s desk, but before Pitcher could say anything, Cummings dove into a rambling saga centered in Valdez, Alaska, where he’d lived for more than two decades. People’s identities were being taken over, Cummings said. A criminal syndicate involving his wife, Karen, had sabotaged his heli-ski business, H2O Guides, and was trying to kill him. While en route to Wolf Creek, Cummings said, a semitruck had belched poison at him through its exhaust pipe, making his heart race. Taken aback, Pitcher tried to change the subject.

The U.S. team is up on the hill (Editor’s note: Quotes in italics have been reconstructed to the best of the sources’ memories.), he said. The team was coached by Caleb Martin, a skier from Telluride, Colorado, who held Cummings in high esteem.

Caleb’s here? said Cummings, brightening at the mention of an old acquaintance. I used to talk to Caleb when I taught avalanche awareness in schools.

Well, let’s go jump on the lift, he’d love to see you, Pitcher said. Cummings made excuses, said he hadn’t brought his skis. Pitcher told him there were thousands of skis and boots in the lodge, some brand-new.

No, I’ve got to go, Cummings said. He wrote down a number and handed it across the desk. I’m meeting an FBI agent in Albuquerque, he’s going to help me. I need you to be the contact. When you see this number come up, answer it. You can pass on information.

Pitcher said he didn’t always have cell service; someone else would probably be better. Cummings looked disappointed. Pitcher had no idea how drastically his friend’s life had splintered—that Cummings, 53, had been divorced, lost his home, lost custody of his three children, and seen his once thriving business implode. Or that Cumming’s behavior would soon lead to a man lying dead on the floor of a trailer in the New Mexico desert.

Cummings got up to leave. He walked back down to the sports car, and Pitcher watched him drive away just 15 minutes after he’d arrived.

“That was the first time in my life that Deano didn’t want to go skiing,” Pitcher says. “It was very sad. It was obvious that he was not within a reality that you could quite buy into. When he departed, I just felt like it was the end of an era. I felt that he was headed for trouble.”

Late 1980s, Telluride, Colorado

Cummings had been one of skiing’s most unlikely heroes. He made his name when straight skis were hip and the hottest discipline in the sport was freestyle moguls—racing down a zipper line of giant bumps as fast and as smoothly as possible, with aerial flair.

To come from the high desert of Los Alamos, New Mexico, and beat people who were training in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, or Aspen, Colorado, was a fantasy, even for a gifted athlete like Cummings, who’d been skiing since kindergarten. But two years after high school, he loaded up his van, the Love Machine, and started following the moguls circuit. Like many competitors, he had no coach. Instead he studied the top finishers and tried to emulate them. He bounced around Colorado to train, sometimes pitching his tent between the ice machine and phone booth at Arapahoe Basin or sleeping in a friend’s yard in Telluride. He called his buddies “Shred” and would often say, “Skiing is life.”

He admired two men who personified that ideal. One was a beautiful French snowboarder from La Grave named Polo who had bleach-blond hair and flashed perilous couloirs in a golden ski suit. The other was a legendary ski bum in Telluride named Himay Palmer. “Deano was a true friend,” Palmer says. “He had this pure love of skiing that I don’t encounter in many people.”

To fund his dream, Cummings worked construction and grew high-grade marijuana to sell during his travels. He learned the secrets of clandestine cultivation from a hippie known as the Master. “Deano would tell me about him,” says Niel Ringstad, a Telluride ski pioneer who met Cummings in 1988. “They were modifying vehicles and putting water tanks in them, and they’d take them out to the middle of the desert where they had drip systems to grow weed in the ultimate places.”

Cummings’s pot was the stuff of ski-town legend—and he smoked plenty himself. “He’d say, ‘I call this the Waiver, because you need to sign a waiver to smoke it,’” Ringstad says. “And he was right. It was ridiculous. When he would come through town, everybody wanted what he had.”

On snow, Cummings eventually caught up to the men he’d been chasing, which only seemed to wind him tighter. He clenched his teeth so much that his jaw muscles looked like golf balls. “I remember him in the woods, punching trees before his runs,” says Brian O’Neill, a longtime friend in Telluride and former H2O guide. “A lot of people have the physical capabilities, but the difference between Deano and everyone else was his willpower. And it showed up in every fucking turn.”

In 1991, Cummings’s third year on the circuit, he qualified for the U.S. development team, then flew to Valdez, Alaska, to compete for the inaugural World Extreme Skiing Championship—the biggest event in the nascent history of big-mountain skiing, which had emerged in the late eighties. He placed second to Doug Coombs, an ex–ski racer from Jackson Hole. The result catapulted Cummings’s career and inspired him to put down roots in Valdez.

Coombs and his wife, Emily, started Valdez Heli-Ski Guides in 1993. Cummings founded H2O Guides in 1995—and won the world title that same year. He slept in an office in town and ran his heli groups out of a van on Thompson Pass. Operators had to push out their chests to establish themselves in Valdez, but Cummings, who grew up steeped in machismo, never stopped pushing out his chest. It didn’t take long for that tendency to create problems.

November 2018, Valdez, New Mexico

Joel Serra opened the door of his home near Taos Ski Valley and found Cummings standing in his gravel driveway. Serra had known Cummings since 1989. He worked as Cummings’s attorney for nearly two decades and guided for H2O until a near fatal avalanche burial in 2006 left him with crushing migraines, ending both his law and guiding careers.

Cummings’s unannounced visit immediately put Serra on edge. It was their first contact since Serra had written his old friend a letter the previous April, detailing what he saw as Cummings’s crippling habit of locking onto a few facts and filling out the rest of the picture inaccurately. He’d urged Cummings to seek counseling in order to save his family. In Serra’s driveway, Cummings apologized for leaving a nasty voice mail in response to the note, and asked Serra to be his lawyer again, a prospect Serra quickly shot down. Instead, Serra suggested that Cummings go see a psychiatrist who lived nearby.

You need help to sort through this, Dean, Serra said. Anybody can need help from time to time, there’s no shame in it. Let me take you.

Cummings pointed at Serra and started turning red. You have to be my lawyer, he growled, taking a couple steps toward Serra.

It’s time for you to leave, Serra said, standing his ground and trying to mask his fear. I’m calling the sheriff. Cummings marched back toward an SUV, then spun around and pointed at his friend again. You’re going down, he said.

Jesus, Dean, what do you mean?

I’ve got you nailed, Cummings replied. Then he left.

Early 1970s, Los Alamos, New Mexico

Cummings had been hot-tempered since his youth. He was born in Albuquerque, the fourth of five children, to Boyd and Carol Cummings, a Mormon couple from Utah. The family moved north to Los Alamos when he was six, and even then he was stubborn. “You could ask him to do something,” says Carol, who now lives in Rio Rancho, New Mexico, “but you couldn’t tell him.”

Boyd worked as an electrical engineer at Los Alamos National Laboratory, where scientists developed and maintained the atomic arsenal that had originated with the Manhattan Project. They were a normal middle-class family in a town that evoked a strange blend of Americana. John Fullbright, who met Cummings in fourth grade and remained his best friend through adulthood, describes Los Alamos as “kind of like Andy Griffith meets Leave It to Beaver and Bonanza. You had cowboys riding around on horses with guns, and lab scientists trying to justify their careers in nuclear physics, making bombs that would obliterate humanity.”

The surrounding canyons and mesas offered ample opportunity for adventure, and Cummings took full advantage, spending almost all his time outdoors. His father had been a ski patroller at Alta, in Utah, and taught Dean and his siblings to ski at Pajarito, a small resort just west of town. Cummings starred in hockey, baseball, and football—as well as the local pastime of leaping off 30-foot cliffs onto steep pumice slopes, whose mushy surface offered just enough cushion for a body to absorb the repeated jars.

School was another story. Cummings struggled with dyslexia and attended special-education classes, which his mother believes caused him to become defensive and a fighter. At Los Alamos High School, he called himself the Marshal of the Woods, and if he saw someone throw a cigarette butt or beer can onto the ground at a party, he’d confront them. Hey, you’re trashing the mountains, and I’m here to tell you to put your shit in the garbage, he’d say, fists clenched.

Cummings fought someone almost every weekend, Fullbright remembers. “He was small, but it’s kind of like a wolverine has an excess layer of confidence,” Fullbright says. “It’ll go against a grizzly. Size wasn’t an issue for Dean. I couldn’t believe the size of some of the people he ended up fighting. Out of 30 or 40 fights, I never saw him come even close to losing.”

Cummings drove like he was being chased and paid the price in violent accidents. Once he fell asleep while driving down a canyon and came to after being ejected from the vehicle. “He wrecked every car he ever owned,” his mother says.

But he focused on a dream, too. Inspired by a backpacking trip with the Mountain Center, an educational and therapeutic nonprofit based in nearby Santa Fe, he told people he was going to earn a living in the wild, perhaps as a guide. When a high school counselor scoffed, You can’t make a life like that, he shot back, Yes. I. Can!

February 2019, Taos Ski Valley, New Mexico

Fullbright was sitting inside Tim’s Stray Dog Cantina, a popular Mexican restaurant where Taos locals gathered after skiing, when he saw his old friend walk in. Cummings’s presence made him uneasy.

About 18 months earlier, in the summer of 2017, Cummings told Fullbright, You’re my last friend on earth. Fullbright had tried to calm Cummings’s mind by stinging him with bee venom, an ancient Egyptian therapy that had aided Fullbright’s recoveries from a lightning strike and Lyme disease. The venom seemed like it was helping Cummings, too, for a while—during one session he fell asleep on Fullbright’s kitchen table for eight hours. But Cummings couldn’t escape his delusions. He’d balanced a water bottle on Fullbright’s door latch in case someone tried to break in and was constantly anxious.

Then, in the summer of 2018, Cummings showed up in Taos riding a motorcycle. He had a handgun strapped to his back, another holstered under his armpit, and a third tucked into his boot. Late one night, he entered Fullbright’s home without permission and curled up in his living room. What the fuck are you doing on my couch? Fullbright said when he came downstairs at 5 A.M. You can’t show up here unannounced. You have to go, and you have to go right now.

As Cummings stood up to leave, he snarled, I loved you when I knew you, but now that I know you’re a murderer, you’re going down.

Soon afterward, Cummings tried to convince Fullbright’s wife that her husband was scheming to kill people. He promised to “rescue” her and her two children from their father. This deepened a rift that remained unresolved when Cummings walked into the cantina that winter.

The childhood best friends locked eyes, then Cummings turned around and left without saying a word.

July 1998, Aspen, Colorado

Karen Stokes knew exactly who Dean Cummings was when she met him, she just didn’t know she was talking to him. A striking blond ballet dancer and lifelong skier from Chicago, she had seen Cummings in ski magazines and movies, but he was always wearing goggles. When someone introduced them at a gear show in Aspen, Cummings gave her his card and invited her to come heli-skiing in Valdez. You’re Dean Cummings? she blushed. She’d been single for a while and was hard to impress, but they talked for hours. After they parted, she couldn’t stop thinking about him. So she wrote him a letter. He called as soon as he got it. Their first date was in Telluride at a film premiere that fall. A few months later, she moved to Valdez and they became inseparable.

Karen was 29 at the time, the youngest of seven children in a Catholic family, and Cummings was 33. They married in 2001 on top of a mountain, flying up their guests by helicopter. “It was like being in a fairy tale,” she says.

At H2O, Cummings was the big-picture visionary with charisma, while his wife, working as the CEO, was organized and patient and made things happen. They held hands when they rode in the helicopter. “He told me I was beautiful every day and meant it,” she says. They welcomed a son, Wyatt, in 2003, then a daughter, Tesslina, in 2005. Eight years later, a second daughter, Brooke, joined the clan. Valdez, a 4,000-person oil town at the end of the Richardson Highway, provided a blissful existence. They woke up to pink sunrises surrounded by nature’s skyscrapers on Prince William Sound, with world-class adventure available in every direction. But there were also warning signs. “He was always a paranoid person,” Karen says. “I thought, Well, that’s kind of weird, but it wasn’t that bad when we were young.”

Heli-skiing could be lucrative, but it was a stressful way to make a living. There were as many as six such companies operating out of Valdez, and most costs are more or less fixed, so the best way to distinguish one’s outfit is by whisking customers to the best terrain.

Cummings had long coveted the U.S. Forest Service permit that Doug Coombs had held since the mid-nineties. After Coombs sold his company and left Valdez in 2000, the Forest Service opened up the application to other operators. H2O won the permit in 2003 and ultimately secured it through 2019. It granted exclusive access to more than 200,000 acres of unending peaks blanketed in white velvet—arguably the best heli-skiing territory in the world. With everyone else left to share smaller, less desirable chunks of state and BLM land, relations were contentious. Cummings defended the Forest Service land like he owned it. He often complained, sometimes legitimately, about poaching by his competitors. They in turn argued that he was underutilizing his permit—because he didn’t take guests into the terrain often enough—and petitioned the feds to share it, without success.

H2O netted as much as $300,000 a year, enough for Dean and Karen to live comfortably in Valdez: they bought a home, two boats, and eventually a plane. Cummings designed a course for heli-ski guides and trained many who went on to have long careers in Alaska. He prized his impeccable safety record, built on unorthodox tactics that some of his former guides still use. “He didn’t do what they say in the book,” says Eric Layton, the first splitboarder to be certified as a ski guide by the American Mountain Guides Association. “They say to dig a pit and analyze the snowpack. Dean would just read the texture of the mountain, understand how the snow came in, how it cooled then warmed or warmed then cooled. He was like the European guides in that sense. He just really understood the mountains in a different way.”

Still, Cummings had a reputation for micromanaging his guides, who tired of his authoritarian ways and frequently quit or were fired. Many called their twice-daily planning sessions “guide beatings” instead of “guide meetings.”

The least known side of Cummings was that of a doting family man. “He could be so intense and hard-driving,” Karen says, “but he just had this whole side of him that was a blast—and hilarious. He laid in bed with his kids every night and told fantastical stories. He was always loving on them, playing with them, or teaching them something.”

When each child was old enough—usually two or three—Cummings took them heli-skiing. He balanced their boots on the tips of his skis and floated through the powder as they giggled in his arms. He coached Little League and wrestled with Wyatt, attended father-daughter dances with Tesslina, and competed in family dance-offs in their living room. It was markedly different from the person his rivals saw, but that was OK by Cummings. “He didn’t have normal friends,” Karen says. “He wanted it to be just our family. And he wanted to shut all the curtains and lock the doors and never be social.”

Beneath Cummings’s chiseled, often antagonistic veneer, insecurity lurked. According to Karen, his dyslexia and struggles in school wounded his psyche for decades. Cummings didn’t learn to read until long after his peers. One night he and Karen were talking in their bedroom when he confided in her. “I pressed about why he was certain ways,” she says. “I remember him telling me that he overheard teachers in the hallway. He was walking behind them, and they were making fun of him. And it just broke his heart, hurt his feelings so badly. He said sometimes he felt so backed into a corner, he wanted to fight everything.”

Cummings broke down and sobbed in his wife’s arms. I’m so sorry, she said. You’re so brilliant. Your brain just works differently.

Cummings’s frequent marijuana use worried Karen, but it was “just weed,” he said, and it helped him focus. “I didn’t know any better,” she says. “I didn’t know I was dealing with a time bomb.” Repeated head trauma mounted, too. Cummings skied off 70-foot cliffs into his fifties, and he rarely wore a helmet. “I assume he had a series of concussions, because he would talk about it,” says former H2O guide Kyle Bates. “Getting his bell rung in competitions, backslapping and hitting his head on big cliff drops, kind of a whiplash thing.”

“I remember him in the woods, punching trees before his runs,” says Brian O’Neill, a longtime friend in Telluride and former H2O guide. “A lot of people have the physical capabilities, but the difference between Deano and everyone else was his willpower. And it showed up in every fucking turn.”

Though Cummings moved on from his street-fighting ways in adulthood, he never lacked enemies. He butted heads most aggressively with other alphas (the Alaskan heli-ski industry has plenty of those), who butted back. He frequently told other operators that they were “riding my coattails” and made a habit of reminding everyone that H2O was the only company allowed to ski the Forest Service terrain.

Cummings had a long-standing feud with Points North Heli-Adventures owner Kevin Quinn, a former professional hockey player who skied with H2O as a client before starting his own company in Cordova. Cummings also battled Josh Swierk, who bought a neighboring piece of land from the Cummingses and proceeded to launch a competing heli-ski company, Black Ops Valdez, in 2013. Swierk and his wife, Tabatha, who worked for H2O in 2004 when they moved to town, say they called the police on Cummings more than 100 times, mostly for noise-ordinance violations.

In 2015, worn thin by her husband’s behavior and disorganization, Karen resigned as H2O’s CEO and got a job at a local phone company. Around the same time, the City of Valdez purchased ballistic shields and installed panic buttons throughout its facilities. According to a city spokesperson, the measures were not in direct response to a particular person’s actions, but one member of the community-development staff remembers that Cummings was discussed as they were taught how to implement the plan. “Literally, when I got trained, someone said, ‘If Dean comes in and starts threatening you’—Dean’s name definitely got used—‘grab this shield to protect yourself,’” says Selah Bauer, who worked for the city in 2016. “With the panic buttons, you’d push them and the police would be there. You didn’t have to call.”

Bauer and another employee requested a meeting with police chief Bart Hinkle, and they discussed Cummings at length. Cummings’s behavior—and the police department’s inability to stop it—still rankles Bauer. “Alaska has kind of a live-and-let-live motto,” she says. “But it also seemed like their hands were tied.”

In April 2020, Hinkle agreed to answer questions via email for this story, then never responded. A spokesperson later said the police chief “will be unable to participate in an interview about Mr. Cummings.”

November 2016, Valdez, Alaska

Karen remembers the day everything changed. It was two months after Cummings’s 51st birthday.

“He woke up and something cracked open in his brain,” she says. “He said people through the wall were telling him I was doing horrific things with other men and people were trying to poison him. He was a completely different person. I was like, ‘OK, now you’re scaring me, Dean. We need to go to the hospital.’”

Cummings agreed to see a doctor, but every time Karen made an appointment, he failed to show up. Still, he realized that whatever had been festering was more serious. “After he had the mental break, he would call me and say, ‘Something’s wrong, something’s wrong,’” Karen recalls. One minute he would be normal; the next, a monster. “I remember talking to him while he was driving home, and he was like, ‘I’m so sorry, I love you so much, we have it so good, we’re going to get through this.’ And he parks in the driveway, we hang up the phone, then he comes in the door and—that fast—starts shouting, ‘You fucking whore!’ It was like a light switch.” When he snapped back to normal, he’d apologize. We’re such a good family, don’t give up on me, he’d plead. Karen was torn. “Of course my heart was bleeding,” she says. “‘OK, let’s get help!’ But he didn’t want to be labeled. He didn’t want to be on medication. He didn’t want anybody to find out.”

Cummings’s volatility led to extensive emotional and sometimes physical abuse, Karen later alleged in sworn affidavits she gave to obtain legal protection from Cummings. He left bruises on her arms from squeezing and violently shaking her. He accused her of sleeping with “no less than 50 individuals,” including many of H2O’s former guides and the family dog. (“He had no reason to be jealous,” Karen says. “Like, none. It was so weird. I had no interest in anyone else. I was in love with my husband.”)

Cummings told Karen he’d considered shooting himself in the head and driving off the road with their three-year-old daughter, killing them both. She noticed his eyes got darker and glassier as the problems persisted. Cummings’s “abuse currently dominates almost every aspect of our family’s life,” she wrote in an affidavit, listing examples that involved the children.

She applied for a short-term protective order in January 2017, then withdrew it at Cummings’s behest. Trying to placate his suspicion that she was stealing from him, she let him take her name off all their bank accounts, a decision that she says helped him abscond with their savings, roughly $355,000 in cash.

Karen was seeing a counselor at the Valdez hospital in the spring of 2017, as well as visiting the women’s shelter, where people warned her that her life and the childrens’ were in danger. Cummings knew his wife had considered leaving and constantly questioned her and the kids about any plan they might be making. “He would literally get in my face—‘What are you plotting? Where are you going?’” Karen says. “He would go through everything of mine on a daily basis—my computer, my purse, my underwear drawer, my phone, which he’d wrestle out of my hands.”

One day in June that year, with Cummings set to leave town for work, Karen drove to the library, sank down in her car, and phoned her sister in Illinois. She said she was ready to leave with the kids. Her sister flew up to help them pack. They took only what they could fit in a few suitcases; the kids left their toys. Karen had roughly $8,000 in cash and a small retirement nest egg to start a new life with three children, now 14, 12, and 4.

“It was like being in a burning building,” she says. “Dean was on fire. I was pulling at him, struggling to drag him out to safety, but he absolutely refused to go, and the kids and I started to burn, too. We had to escape or we would have died with Dean.”

They boarded a flight on June 20, knowing they might never return. Karen called her husband once they were out of state: “I said, ‘The kids and I are safe, and we are not coming home.’ Then I quickly hung up.”

July 2017, Lake Forest, Illinois

They moved in with her sister outside Chicago. Karen obtained a two-year domestic-violence protective order that prohibited Cummings from contacting them. A messy divorce soon followed. After her retirement savings ran out, she dipped into the kids’ college funds to get by.

During their custody hearing, Karen obtained a court order requiring Cummings to undergo a psychological evaluation. But he fought it. “At no time has a medical provider recommended or referred Mr. Cummings to a mental health professional,” his attorney wrote. “He has exhibited no behavior necessitating a mental health evaluation.” Cummings never complied with the court’s order, and no one ever enforced it.

Meanwhile, Cummings became convinced that someone had built an underground pipeline to his house and was pumping in poison gas. He thought a wayward straw left behind in a can of soda was a listening device. He sniffed carpets on his hands and knees, and told people that he was carrying a mouse in his jacket pocket to taste his food.

Cummings constantly complained about his fluttering heartbeat and insisted that other organs had been tainted. I feel it on my spleen, he’d say. In early 2018, H2O’s operations manager, Abe Pacharz, arranged for Cummings to undergo a five-day inpatient physical at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota. After the fourth day, however, Cummings called Pacharz and said he was at the airport.

Don’t you have another day? Pacharz asked, surprised to hear from him.

Yeah, Cummings replied, but the last day is the psych exam. I just pulled out all the tubes and left.

Pacharz lived in his camper in the Best Western hotel parking lot where H2O was based. One day, while he was eating lunch, he saw Cummings walk out of the hotel. Hey, come check this out, Cummings said, pointing to a blue patch of ice under his truck. Fuck is that shit?

Pacharz guessed it was antifreeze, wiper fluid, or Gatorade. Chip that up and put it in a bag for me, Cummings said, explaining that he kept a cooler full of “samples” that he was having forensically tested in Denver, along with pieces of his hair. Every so often, Cummings would say he’d heard back from the lab. I got the results, he’d say. That shit is in there. It’s in my hair, man!

Cummings had maintained enough of a stable appearance to keep H2O operating more or less normally in 2017, but his mental cracks widened in 2018. Perhaps most telling, his staff saw his vaunted safety protocols get looser. Cummings would misplace his guide pack and once took two rookie employees skiing without harnesses—mistakes he never used to make.

“It was significantly and obviously different from the year before,” says one veteran guide, who spoke on the condition of anonymity.

A few weeks into the 2018 season, Cummings’s entire staff quit. One of his pilots, Peter Pelayic, arrived soon after the exodus to find a group of backcountry skiers who Cummings had hired off the street to be his guides. The men received an intensive week of training, but to Pelayic, who had flown for decades, it still seemed like they weren’t qualified for the job.

![Cummings teaching terrain management to prospective guides in 2003. “[He] would just read the texture of the mountain, understand how the snow came in, how it cooled then warmed or warmed then cooled,” remembers guide Eric Layton. “He was like the European guides in that sense. He just really understood the mountains in a different way.”](https://www.outsideonline.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/19/teaching-terrain-management_h.jpg)

July 2018, Anchorage, Alaska

Dean and Karen’s divorce was settled in Alaska Superior Court three months after the heli-ski season ended. In a ruling that granted Karen sole legal custody of their children, judge Jennifer Henderson wrote: “The Court finds that Dean’s actions are a result of his delusional and paranoid behavior. The Court will not assume Dean’s diagnosis, but it is clear from the evidence presented that this behavior was a result of a mental breakdown of some kind that led to his abuse toward Karen and the children.”

The National Alliance on Mental Illness estimates that more than 13 million adults experienced serious mental illness in 2019, defined as a mental, behavioral, or emotional condition that substantially interferes with a major life activity. But in general, the incidence decreases with age, affecting only 2.9 percent of people over 50 in 2019, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Cummings is 55. It’s impossible to say what caused his breakdown, but a general rule applies. “You’re more likely to have mental health problems if you have cognitive and emotional problems earlier,” says Harvard Medical School professor Thomas Gutheil, one of the top forensic psychiatrists in America.

According to Gutheil—who has never met Cummings and made it clear that he was not trying to diagnose him—everyday paranoia exists in far more people than the condition ultimately destroys. “It’s not a disorder until it gets out of control,” Gutheil says, noting that such cases can escalate to “full-fledged delusion.”

Head injury and dementia can both trigger paranoia. Marijuana, too, is known to promote psychotic thinking and paranoia in some people. But, Gutheil says, there’s often no way to say definitively what causes anyone’s paranoia.

By the time Judge Henderson tied Cummings’s breakdown to his domestic abuse, he had packed up and left Valdez to start fresh in Jackson Hole. He told people that he’d rented an office and was thinking of starting a heli-ski company in Wyoming’s Star Valley. Mainly, though, he trumpeted his conspiracy theory to anyone who would listen—and, at the time, there were still plenty who would.

Cummings told Karen he’d considered shooting himself in the head and driving off the road with their three-year-old daughter, killing them both. She noticed his eyes got darker and glassier as the problems persisted.

The accusations were “galactic,” in the words of a former guide who Cummings accused of stealing from him. He never provided any proof, but some of his friends took notes the first time they heard it, just in case he was right. “It’s not like talking to some street urchin who’s drooling on you,” says Chris Carson, a longtime friend from Colorado. “He could dance through society with no problem, and on the surface be able to interact with people. But as soon as the story started coming out, it was just, whoa.”

Notably, Cummings seemed convinced that Karen had been sent to steal his client database in 1999, and that was the only reason they ever met. He told people that the Exxon Valdez oil spill and 9/11 were conspiracies. He said he was “on a mission” to expose it all.

“It was like a hundred-chapter novel,” says David Hodges, a sheriff’s detective from Teton County, Wyoming, who Cummings visited in October 2018 (Cummings also sought out law-enforcement officers in Alaska, Utah, Colorado, and New Mexico). “He’d start out at chapter 47, then all of a sudden he’d bounce to chapter 18. I’d try to get him to start over at chapter 1, and that would last just a short amount of time and he would go back to chapter 72.”

Hodges eventually got in touch with Karen, who gave him the backstory and explained that she and Cummings’s family were desperate for Cummings to be detained and undergo a psychological evaluation. “And I told Karen, Dean demonstrated no behavior to me that I could take such restrictive action—he never mentioned violence toward himself or others,” Hodges says.

In early January 2019, Cummings released a rambling, 20-episode YouTube series that he called How a Criminal Syndicate Tried to Destroy a Man’s Company and Life. An unidentified young man shot it in venues ranging from the desert to a parking garage, where Cummings laid out his manifesto—with multiple tangents. One minute he railed against human traffickers, the next he pushed for climate-change awareness and lamented the receding glaciers in Valdez. During the series, which was released over a ten-day period, he denounced many of his former clients and guides by name. “Their most desperate plea was trying to say that I was,” he said, making air quotes—“psychologically messed up. After everything I’ve dealt with and seen and done over the last two and a half years with this ordeal, I’d have to say I’m a pretty solid person.”

It’s unlikely that Cummings was aware that the Forest Service suspended his permit on February 1, 2019, after he failed to address a litany of noncompliance issues. On February 21, he told a client—who’d wired him nearly $8,000 for a week of skiing in March—to rest assured, the trip is still on. The Forest Service officially revoked his permit on March 3, sealing the end of H2O’s 24-year existence.

July 2019, Rio Rancho, New Mexico

Cummings floated between Colorado, Wyoming, California, and New Mexico from late 2018 until the following summer, when he moved in with his parents in Rio Rancho, a suburb of Albuquerque. It didn’t take long until they, too, became part of his conspiracy. He claimed his mother was poisoning their shower water and stealing his sponsor checks. Carol, 81, said he thought a castle in Scotland had been stolen from the family and that they needed to get it back. “Why? Because our last name [is Scottish],” she says.

He investigated his father’s friends from church and reported his siblings to the FBI for bizarre transgressions. “All our family is welcome here,” says Boyd, 86, who still calls Dean “Sunshine.” “The door is always swinging. I can’t keep it shut.” But when their son showed up, the door stopped swinging. “The kids wouldn’t come. His brothers and sisters, he made an enemy out of all of them.”

About six months after Cummings moved in, he told his parents that he was considering moving out. He’d found a desert ranch for sale 90 minutes northwest, near a 50-person village called San Luis, and he drove up to see it around Christmastime. Flanked by red-rock mesas and little else, the remote site seemed to be his best hope of finding any semblance of peace for his racing mind. There was no internet to feed his theories. No neighbors nearby to worry about. Few signs of life at all, other than vultures picking at roadkill and sage swaying in the breeze.

The ranch’s owner, Guillermo Arriola, was a 47-year-old landscaper from Placitas, a traditional New Mexican town at the base of 10,678-foot Sandia Crest. Roughly 5,000 people live in Placitas, including descendants of the original Spanish land grantees as well as hippies who arrived in the 1960s. Arriola, the youngest of seven children, was a lifelong resident and shared the family home with his father, who was 86 and legally blind. They no longer raised livestock on their 1.25 acres, but they grew a wide range of fruits and vegetables, from chiles and watermelon to squash and garlic, to feed their extended family.

Arriola started working when he was 11 and never stopped. He built a successful business and a reputation for bridging the gap between the local Hispanic and gringo communities. “He was such an honest, straight-up, hardworking guy,” says Donna von Stetten, who has lived in Placitas for 43 years and has known Arriola since childhood. “He liked to help people who couldn’t help themselves,” says one of his four sisters, who served as the family spokesperson but asked not to be identified by name.

Arriola’s late mother had grown up on her family’s 16-acre cattle ranch near Cabezon Peak, a 7,786-foot volcanic plug just south of San Luis. The ranch was passed down to Arriola and his two brothers; when his brothers died in separate traffic accidents, it became his. The location was too remote to live there full-time, but Arriola took great pride in keeping it up. He built out a mobile home and grew cherry, peach, and apple trees while battling rattlesnake infestations. A solar-powered pump drew water from a nearby well.

Every weekend, Arriola drove up from Placitas to escape the tangles of society and sit on his porch in the quiet. He bugled for elk, watched the sunset. But his primary pleasure came from riding his beloved horse, Corona, an eight-year-old Arabian pinto who lived to run. He brought her home from Colorado when she was a foal and rode her in Placitas’s annual Fourth of July parade. “You’d drive up to the ranch with him, oh my gosh, she’d be over the moon,” Arriola’s sister says. “He’d be hugging and kissing her. I’m like, ‘Guillermo!’ But he’d say, ‘Just leave me alone, she’s my baby.’”

Arriola did anything for his family. He lived with one of his sisters for 14 years and helped raise his niece. “He’s the only father she knows,” his sister says. He always wanted a family of his own and had plenty of suitors, but, according to his sister, he never could find a woman who matched up to their mother. Instead he mentored local kids who needed jobs and helped them plan their futures.

He had his flaws. He’d been arrested for fighting and had periodic disputes with other Placitas locals, mostly while standing up for his family. “We all have our things and try to protect what we think is right,” his sister says. “I’m sure he did, too. But his biggest thing was forgive and forget.”

Hard labor made Arriola tough. He hunted with a bow and rifle, mainly for elk and deer but also javelina and wild turkey. He was what von Stetten called “a gentleman cowboy.”

When Arriola’s father lost his vision five years ago, he knew he was going to have to spend more time at home, helping his dad get around. He considered selling the ranch. “But he struggled with that, because he loved being out there,” his sister says. “That was his joy.”

On Thursday, February 27, 2020, Arriola’s sister asked him if their family could spend Easter at the ranch, where his many nieces and nephews rode horses and roamed freely. “He told me no, because this guy who was interested in buying the ranch had been out there for two weeks and they were finalizing paperwork,” she says. “That’s how we found out that he was selling the ranch. How they met, I have no idea.”

It’s unclear what price Arriola and Cummings were deciding on, though according to the Albuquerque Journal, Cummings later told a Sandoval County Sheriff’s deputy that Arriola wanted $1 million for it, a preposterous price in an area where land sells for $3,000 to $7,000 an acre.

Before leaving his parents’ house, Cummings loaded up all of his belongings, apparently intending to stay at the ranch. His father remembers his son being skeptical of the deal’s legitimacy, but by then, Cummings seemed to be skeptical of everything.

February 29, 2020, San Luis, New Mexico

The man approached David McCulloch just after 5 P.M. McCulloch, a retired physician’s assistant from Albuquerque, had been riding his motorcycle on the unmarked dirt roads near Cabezon Peak. He might see just one or two vehicles a day on the rugged desert doubletrack, which crosses a series of deep arroyos and winds through the scrub brush for miles. The Continental Divide runs along a mesa just north of where McCulloch, 66, stopped to check out a point-of-interest sign.

The man pulled up in a white flatbed truck. He made small talk about McCulloch’s bike and then drove off, only to return a minute later and launch into a story that was hard for McCulloch to follow. He said people had tried to kill him several times and had ruined his business.

With the winter light fading, McCulloch edged toward his bike to begin his ride home. The man waved him back. Do you have cell-phone service?

McCulloch checked his phone; he did.

Well, the man said, can you call 911 for me? I can’t get through.

McCulloch dialed and reached the Sandoval County Sheriff’s dispatch. “What’s going on?” the dispatcher says. “Are you lost?”

“So, the reason I’m calling,” McCulloch says, “is I ran into a guy here who says he was attacked at a ranch and he wound up pulling a gun and shooting the guy who attacked him. And he can’t get cell service and he asked me to call 911.”

“OK. Does he know if the other male is still alive, or does he not know?”

McCulloch addressed the man before him, later identified as Dean Wayne Cummings. “Do you know if the guy is alive? … He says no.”

“What kind of vehicle is he in?”

“He’s in a Dodge Ram 5500. A big sticker on the side says ‘H2O Guides.’ He said it’s some sort of helicopter-ski-guide service. It has an Alaska plate.” The call then got disconnected.

Can you be a witness? McCulloch says Cummings asked him.

A witness of what? McCulloch replied.

Well, this guy had this black thing that he was trying to poison me with.

December 2019, Anchorage, Alaska

When Judge Henderson renewed Karen’s long-term protective order against Cummings two months before the shooting, she checked a box next to this line: “Respondent represents a credible threat to the physical safety of petitioner.” Under state law, Henderson could not prohibit Cummings from possessing a gun, since he hadn’t used a gun during his acts of domestic violence—even though he was known by the court, as well as by law enforcement, to be armed and mentally unstable. (As early as November 2017, an Alaska state trooper reported to the Valdez Police Department that Cummings had cornered him in the grocery store and was “presenting what appear to be classic signs of schizophrenia.” Hinkle, the Valdez police chief, later told a colleague that he had been documenting Cummings’s “delusional behavior.”)

However, a federal statute—18.USC.922(g)(8)—does prohibit a respondent in a long-term protective order from possessing a gun, as long as the order meets certain conditions, which Cummings’s order did. This particular statute applies nationwide, meaning Cummings wasn’t legally allowed to possess a gun in any state. The problem is that it’s rarely enforced. “This is not an unusual situation—this is the practice all around the country,” says David Keck, project director at the National Resource Center on Domestic Violence and Firearms. “It’s pretty clear that these prosecutions would be easy to do. I just don’t think it’s anybody’s priority, and I don’t know why.”

About a week before Cummings encountered McCulloch in New Mexico, an FBI special agent based in Anchorage called Karen to inform her of allegations that Cummings had stolen money from clients who paid for 2019 heli-ski trips that never happened. (The U.S. Attorney’s Office has so far declined to prosecute the case.) During the call, Karen says, she told the agent that Cummings had several guns and that he had violated the protective order on multiple occasions. That information alone was enough to justify an arrest. Had it happened, Cummings wouldn’t have been allowed to possess guns for the duration of the order, which ran until December 2020. One prosecutor, who spoke to me on the condition of anonymity, says “it’s a fair question to ask” why the agent didn’t act on the violations. An FBI spokesperson in Anchorage declined to comment on the specifics of the case, citing an FBI policy not to confirm or deny investigations.

John Fullbright, Joel Serra, and Cummings’s parents also spoke to FBI agents about Cummings, but it’s unclear whether those agents were aware that he was armed and had a long-term protective order in place that met the conditions required to enforce statute 922(g)(8). Fullbright made his final plea to an Albuquerque agent days before the shooting. “I said, ‘I’ve known this guy since elementary school, and he’s about to snap,’” Fullbright recalls. “‘Just go pick him up and say you want to talk to him. You’ll prevent somebody from dying.’ And the FBI agent said they get, like, 20 calls a day dealing with situations like Dean, where they’re threatening to do this or that, talking big, talking crazy. What do you do? Do you just go to somebody and say, ‘Look, I’ve had a lot of interesting phone calls, and give me all your guns?’”

Unlike in Alaska, New Mexico law would not have permitted Cummings to possess a gun, because he was the respondent in a protective order. New Mexico also passed a red-flag law, allowing peace officers to petition a court to take away someone’s guns if they are deemed a danger to themselves or others. Although that law was signed on February 25, 2020—four days before the shooting—it didn’t go into effect until a few months later.

Cummings could have been detained and forced to undergo a psychological evaluation, which might have triggered further safety measures. Involuntary commitments to mental health facilities were the norm a couple generations ago, until a series of court decisions in the sixties raised the bar for admission. Recently, the pendulum has begun to swing back toward easier commitment, but it still requires instigation. In Alaska, anyone can petition for a court order to detain someone against their will and have them evaluated, including law-enforcement officers. According to recently retired Sandoval County district attorney Lemuel Martinez, the situation is similar in New Mexico: “Probable cause must exist that he will hurt himself or another person. That’s it,” Martinez says. The problem with probable cause is that it’s subjective, and the ample warning signs Cummings scattered around the West went unheeded.

February 29, 2020, San Luis, New Mexico

Despite Cummings’s assumption that the man he shot was dead, McCulloch wondered if he was wrong and the victim was still alive. He agreed to follow Cummings back to the ranch. They bumped several miles down a winding dirt road, then reached a metal gate. McCulloch followed Cummings inside a tan mobile home, where he observed a man, later identified as Arriola, lying facedown on the floor and clutching a black canister in one hand. There was no movement or breathing. A blood-soaked hat rested nearby. It was obvious to McCulloch that Arriola was dead.

See that black thing? Cummings said, according to McCulloch. He was trying to poison me.

They walked outside. Cummings pointed to a water spigot. I had to wash all that stuff off, he said. It was burning my face, burning my eyes, making me sick.

At the Veterans Affairs hospital in Albuquerque, McCulloch had treated patients with conditions ranging from PTSD to paranoid schizophrenia. He knew to use relaxed, nonthreatening body language to gain a person’s trust.

OK, he said, I’m going to go back and wait for the police, and I think you should, too. I think you need to know you’re in big trouble, and you need a lawyer.

What? Cummings responded, according to McCulloch. That guy attacked me. I’m completely innocent. I was defending my life.

That may be true, McCulloch said, trying to make sense of the scene in front of him. But at this point, there’s a dead guy on the floor, your gun did it, and you’ve admitted that you shot him. Everything else is conjecture.

What actually happened remains unknown.

The man pulled up in a white flatbed truck. He made small talk about McCulloch’s bike and then drove off, only to return a minute later and launch into a story that was hard for McCulloch to follow. He said people had tried to kill him several times and had ruined his business.

Cummings said he would be right behind McCulloch, but when McCulloch reached the point-of-interest sign, he realized Cummings had not followed him.

At 6:26 P.M., Sandoval sheriff’s deputy Hayden Walker met McCulloch at the sign. McCulloch guided Walker and two other officers down to the ranch, where they waited for backup in the dark. Five minutes later, Cummings started driving toward them. At least one deputy set up with an assault rifle trained on the truck, while Walker barked commands into a loudspeaker. He ordered Cummings to get out of the truck, walk toward them, and hit the ground in a prone position. They handcuffed him just before seven.

“I wasn’t trying to hurt anybody,” Cummings protested, in audio captured by Walker’s bodycam. “I’m as devastated as…” He trailed off.

Cummings explained that he’d left his gun, a black assault rifle, on the stairs to the porch and removed the magazine. He said Arriola was inside the home. “And whatever he jammed in my face, it emitted some sort of, I don’t know what it was, chlorophyll or something.” (Deputies identified it as a canister of mace in the police report.)

“Hey, one other thing,” Cummings added. “Right after I came out of the house and started washing myself off, a plane came down and circled the property three times. This is a pretty big operation, whatever it is.”

Walker turned to the other deputy, out of earshot of Cummings. “This guy sounds pretty 2711,” he said, using a code for intoxication or drug impairment. “Yeah, I know,” the deputy replied.

The magazine that Cummings removed from his rifle contained nine rounds with painted green tips, commonly seen on armor-piercing bullets. In his possession, officers found seven cell phones, three laptops, two other guns, and more than $20,000 in cash.

Cummings was initially charged with first-degree murder, concealing his identity, and felony tampering with evidence. For the most serious charge, a grand jury indicted him on only second-degree murder. Cummings, who has maintained that he was acting in self-defense, has pleaded not guilty. News of his arrest broke the following week, stunning people throughout the ski and outdoor industries.

Though the headline was shocking, many who had been in Cummings’s orbit since 2016 were not surprised by the outcome. Some privately exhaled, grateful to have not been his victim after fearing for their own lives for years.

July 2020, Rio Rancho, New Mexico

In a sport where being called “crazy” is often a compliment, few of Cummings’s contemporaries knew how to regard someone who fit the term’s clinical meaning. Some cited his history of starting trouble and posted spiteful responses online after his arrest. Others stood up for him and blamed his decayed mind. “This isn’t a tale of savagery,” said former H2O lead guide turned Cummings nemesis Will Spilo. “This is a tale of mental illness.”

Four months after the shooting, I drove to meet Cummings’s parents in Rio Rancho, where their home looks out at the Sandia Mountains to the east. Boyd, a thickset man with wire-rimmed glasses and white hair, greeted me at the front door. Carol, wearing a blouse and makeup, ushered me in. A framed photo of them with Karen and the kids sat on their kitchen counter. Many of Cummings’s belongings cluttered their garage, including two dusty pairs of powder skis. His dirt bike was parked in a shed out back.

“Is there a way to make sense of what happened?” I asked as we sat down for lunch. “No,” Carol said. “He had a good wife, sweet children, money, he loved what he was doing, he loved everything about the mountains. And all of a sudden, it’s gone. And he destroyed it. And I can’t believe if he were in his right mind that ever would’ve happened.” She was trying to remain hopeful that medication would help her son. She was also “numb” and tormented by guilt. “I keep thinking, How could I have fixed it? You can’t help but think that. What did I do wrong? Dean said I did nothing wrong, bless his heart. It makes me feel better, but still. This is my baby boy.”

From Rio Rancho, I drove north to Taos to see Fullbright, whose truck has a bumper sticker that reads: “Adventure Is the Cure.” More than a year after Cummings turned on him, Fullbright still defends his friend. “There’s honor in there, there’s respect in there,” he said as we stood around a fire on the Rio Pueblo de Taos. But he’d installed a motion-detection camera at his home and lived in constant fear of Cummings returning. “It’s fucking rough, man. When somebody’s crazy, what do you do? You can’t tell them they’re crazy. You can’t show them they’re crazy. It’s like this lady told me—when you’re arguing with someone like Dean, you’re trying to empty the ocean with a teacup.”

While Cummings’s loved ones mourned him as if he were dead, Arriola’s loved ones mourned someone who actually was. Placitas residents struggled to process the loss of a native son. The crowd at his funeral spilled out of the Presbyterian church that his grandfather helped build. “He’s not a forgotten victim here,” von Stetten said. “We all lament the loss of Guillermo.” Meanwhile, 55 miles northwest, a despondent Corona did the same. “We’d go out to the ranch every weekend,” Arriola’s sister said. “Corona would just look at us and walk away. There was no joy in her.” When they hung Arriola’s clothing on the fence, the horse took one of his jackets in her mouth, tossed it in the dirt, and laid down on top of it, taking comfort from his scent.

Cummings—or “the skier,” as one Placitas local referred to him—faces a possible 19 and a half years in prison for the combined charges. In May, he was deemed incompetent to stand trial and remanded for treatment at the state psychiatric hospital in Las Vegas, New Mexico. Eight months later, at a hearing on February 11, a judge determined that Cummings is now fit to be tried in court. A trial is tentatively set for January 2022. (I sent Cummings a letter shortly after his arrest but received no reply. In February, his public defender answered questions about his legal status but did not confirm or deny any other facts about the case.)

I asked Arriola’s sister what she thinks should happen to Cummings. “I want them to give this man some help, because not only has he hurt our family, he’s hurt his own family. So I pray that God gives him forgiveness and mercy, and I pray that they can help him,” she said. “Because obviously a lot of people knew what he was headed for, and nobody was able to help him. God needed my brother. His final job was to get this man help.”

August 2020, Salt Lake City, Utah

On a hot Friday afternoon near the end of summer, I met Karen, Wyatt, and Brooke Cummings at Sugar House Park, an expanse of greenery and trees beneath the craggy Wasatch Range (Tesslina opted not to join us). We sat at a picnic table under a pavilion. I asked Karen how she was doing. “I’m OK,” she said. “I have nightmares of him slitting my throat in front of the kids. But I’ve been a lot better since he’s been in jail. I feel a lot safer.”

Karen believes Cummings’s case exposes several gaps in society’s understanding and treatment of mental illness. For starters, she said, people need to realize that, in certain cases, there is a window to get help, and it closes. She admitted that she grew conditioned to Cummings’s behavior over the years, which became part of the problem in the end. “He had the precursors his whole life, and there are so many people who do, too, and need to recognize what’s happening and get help,” she said. “I just didn’t know what I was dealing with. He didn’t know. But it’s never going to get better, it’s only going to escalate unless it’s treated.”

In addition, she argued that loved ones should be more easily able to force psychological exams instead of leaving the decision up to someone in Cummings’s state. “If Dean had cancer, he would’ve been able to logically make decisions about his health care,” she said. “But with a mental break, he had zero logic. I reached out to everyone I could—the hospital, counselors, the police, the women’s shelter, lawyers. They all said the same thing: ‘Nothing can be done until he hurts you or himself.’” In reality, what Karen was told wasn’t entirely true—there were ways in which someone could have intervened given the facts at hand; they just weren’t obvious or without risk.

Stigma, whether perceived or real, remains a plague for someone as proud as Cummings. But the biggest problem, in terms of how it relates to this case, Karen stressed, is that he was allowed to keep his guns. “There is no reason mentally ill people should be allowed to have firearms,” she said.

To cope, Karen prays and goes to church. She talks to her siblings and posts sticky notes that say, “If you’re not green and growing, you’re ripe and rotten.” She also meditates, runs, practices yoga, and attends regular counseling sessions, as well as a weekly meeting for loved ones of people with mental illness. Her kids have received counseling, too. Their family’s ground rule is that they can talk about their dad at any time—and they do, daily. “Dean is a part of who we are,” Karen said. “There are two dads, the one we know loves us and the other dad that is not OK.”

To honor their memory of the former, Karen placed photos of Dean with each of his kids in their respective bedrooms. A framed picture of him skiing powder in Valdez hangs in their living room, along with a map of their former permit with all the landing and pickup zones marked in pencil. Karen tries to keep teaching her children the lessons he taught. “My kids are a huge inspiration to me,” she said. “As hard as it is some days when I want to just lie in bed and hide under the covers and scream my lungs out and cry, I peel myself up to do better by them. They deserve better, they deserve more.”

Karen says that Cummings left her in debt and ruined her credit. She worries she’ll never be able to get a loan again or buy a new vehicle if her current one dies. “I go through really angry periods, where I’ll be like, You fucking ruined my life, you asshole,” she said. “And my kids’ lives. All that hard work. He just stripped us of so much.”

She tries hard to balance those feelings with more productive ones—and to honor her own loss, which often gets buried by the aftermath. “I loved Dean so much,” she said through sobs. “He was my soul mate.”

She and her kids send Cummings letters and photos and care packages, along with money that he uses to order gifts for them. Brooke recently received a pair of flippers that she raved about when we met.

It’s unclear whether Cummings has been diagnosed. He has misspelled and mixed up his kids’ names. But he has also started taking medication and was showing signs of improvement as of December 2020. He talks to Karen and his kids, as well as to his parents and one of his sisters, giving them hope.

It is hard to grasp what Karen endured as a parent and spouse—how she survived, the trauma she still grieves. Dissociation would have been safer than baring her wounds for public consumption. But lest anyone confuse her motive, she does not want sympathy. “I want to help make sense of this tragedy,” she said. “I want my kids to be proud of their dad.”

Seven-year-old Brooke fidgeted at her mother’s side while holding their puppy’s leash under the table. Karen explained that Brooke loved to snuggle with her father.

“Do you remember going out in the ocean in the big boat with Daddy?” she asked her daughter.

“Not really,” Brooke said.

“No? That was your last trip with him.” Karen turned to me. “He took the kids shortly before we left, and they did an overnight and went fishing out in the sound.”

Wyatt is 17, a muscular six-footer, already taller than his dad. He’s a senior and the starting catcher on his high school baseball team, the same position his dad played. He got straight A’s last year and loves skiing powder. But he doesn’t want to be a guide.

Quietly, Wyatt recalled his dad teaching him to fish and tie knots and field-dress animals while hunting. He learned to drive when he was eight and to operate an excavator at 12. He and Dean hunted moose and goat and fished for salmon and halibut. “He taught me how to respect animals, don’t take what you don’t need,” Wyatt said. He inherited his love of Johnny Cash from his dad. Though his memories of the scary times in Valdez have faded, he can still picture the hole his dad punched through a door when he got angry. He hasn’t seen his father in three and a half years.

Wyatt tries to think of the positives rather than the negatives. “I’m so grateful to have a home, food, a bed, A/C,” he said. Still, he worries about his dad. “Just how he’s doing, right now,” Wyatt said. “I feel bad for him. I feel bad for people he’s hurt, too. I feel bad that he lost control.”