Paddling One of the Most Hazardous, Remote Rivers in the World

For years, Chuck Thompson dreamed of picking some random spot on the map of British Columbia and plunging in for an adventure. He got all he could handle and more on the Klinaklini River, a Class V rager that cuts through heavily forested wilderness north of Mount Waddington. In fact, he's lucky he got out alive.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! Subscribe today.

They don't even ask for ID at the Port hardy airport. I just give the woman at the counter my name and she prints my ticket, no further questions.

There’s no security check. No body scanner, either. This means my Dasani water bottle and nail clippers, not to mention the two knives in my daypack, will get on the plane with me. Did someone slip Canada a couple of Xanax while no one was watching?

It’s a promising start. Here on the north end of Vancouver Island, the trials of what Joseph Conrad once called “the hazardous enterprise of living” already feel distant.

Which basically means everything is going according to plan.

If you fly up the Inside Passage between Seattle and Juneau and look inland as the Alaska Airlines 737 is cruising north of Vancouver Island, you’ll see an untouched horizon of serrated peaks, alpine valleys, electric blue glacial tarns, twisting river narrows, and what otherwise appears to be the most uninhabited, unspoiled territory imaginable. Do that flight as many times as I have—I grew up in southeast Alaska—and at some point you’ll wonder: What’s down there? How do I get to it? And once I do, how am I supposed to traverse that lonely wilderness and come out the other side?

As it happens, there are answers to these questions. After decades of fascination from above, and a recent burst of research that included rambling phone conversations with every Tom, Dick, Bob, and Doug who has a gnarly B.C. story to tell, I’ve finally found a way to experience what may be the least visited world-class backcountry in North America.

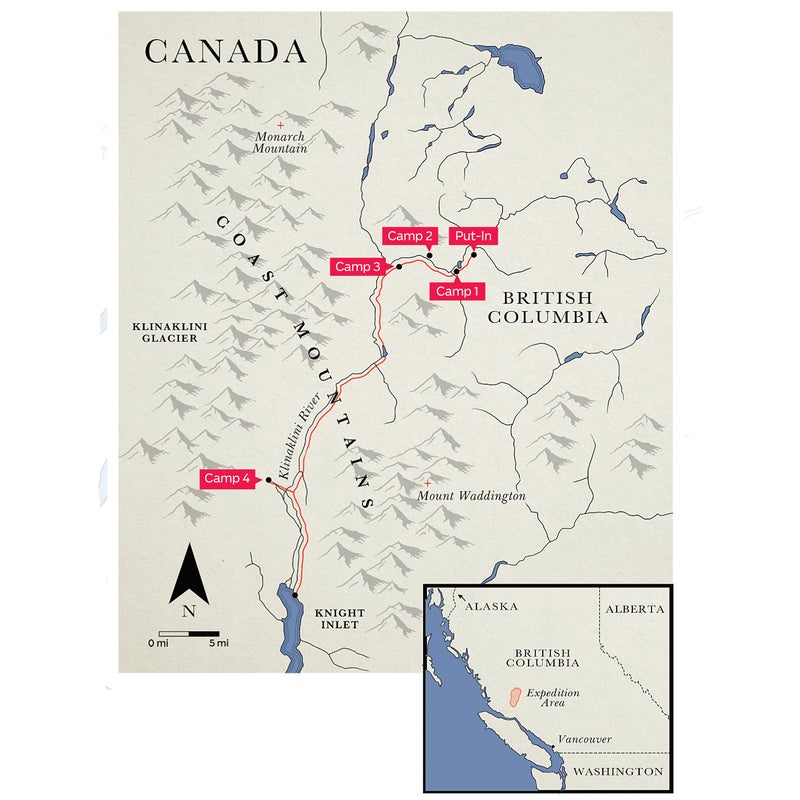

The most dramatic way to explore British Columbia’s central coast is to paddle the Klinaklini River, a 125-mile ribbon of whitewater that runs on a northeast-southwest diagonal through the Coast Range, from B.C.’s central plateau to the Pacific Ocean. It’s an otherworldly passage where peak flows can reach 4,500 cubic feet per second.

In addition to miles of pushy rapids, the Klinaklini runs through gargantuan mountain scenery (including B.C.’s highest peak, Mount Waddington, at 13,186 feet), hanging glaciers, and watery chicanes, as well as grizzly, moose, mountain goat, eagle, and salmon habitat. It finishes alongside orcas and First Nations villages, the river dumping into wide Knight Inlet.

The Klinaklini was part of the region’s fabled grease trail, a network of overland routes that connected inland native communities with coastal tribes who prospered by harvesting eulachon, a small smelt fish rendered into a prized cooking oil and used for trading.

Through this ruthless wilderness, coastal natives marched with huge caribou- and moose-hide packs filled with eulachon to trade for meat and furs. Eulachon were (and, during rare good years, still are) harvested in heavy quantities up and down the coast, especially in the lower estuaries of the Klinaklini.

Paul Mick's Footage of the Klinaklini Trip

This highlight reel offers a glimpse of just how intense the Klinaklini can be

Although it runs through one of the most spectacular landscapes in the world—the Coast Range stood in for the Himalayas in Seven Years in Tibet—there are no settlements along the river, making it ideal for those weary of the set-up-an-account-first mandate of modern times. Paddling the thing is such a hazardous and logistically heavy effort that almost nobody does it.

“Float the Grand Canyon and on any given day you’ll be doing the trip alongside 200 other people,” says Brian McCutcheon, owner of the B.C.-based adventure company Rivers, Oceans, and Mountains. “On the Klinaklini, maybe 200 people total have done the trip. Ever.” In 1997, the Canadian adventurer, now 53, led the first known rafting expedition down its length.

“We took two rafts, a crew of guides, and a French chef and ran it,” McCutcheon says. “We had no idea what was around every corner.”

Sometimes called Canuck Norris—you can see a little physical resemblance—McCutcheon has since guided every known commercial trip but one down the river. Eighteen by his count.

“The Klinaklini is one of the best river trips on the planet,” McCutcheon e-mailed me in the winter of 2015. “It’s got Tatshenshini mountain and glacier scenery with Futa-like whitewater and Yangtze-like consequences. Best of all, there’s no one else there. I’m doing a trip in July. Let me know if you want in.”

At six-foot-five and 235 pounds, McCutcheon has the kind of deceptively athletic build you get in the woods, not the gym. Hair the color of an old dirt road. Salt and pepper stubble. Hands that have tied and untied a million knots. He’s most himself in a flannel shirt, a down vest, lightweight outdoor pants, and river sandals. “Classic lumbersexual” is how he describes the look.

One reason McCutcheon keeps running this daredevil trip is that he’s convinced we’re all becoming pussies—his word, used a lot—and he’s not the type to take bad news lying down.

The bottom is dropping out of the adventure-guiding market, he tells me.

“Kids don’t want to come out and do this stuff,” he grumbles. “The two biggest questions we get from people coming to my lodge are ‘Do your tents have en suite bathrooms?’ and ‘Do you have Wi-Fi?’ ”

“Float the Grand Canyon and on any given day you’ll be doing the trip alongside 200 other people,” says river guide Brian McCutcheon. “On the Klinaklini, maybe 200 people total have done the trip. Ever.”

On July 5, 2015, we fly from a small settlement at Nimpo Lake to the put-in at Schilling Lake—which doesn’t appear on most maps—in a 1949 Canadian-built de Havilland Beaver. Serial number 55. That means it was the 55th one ever made.

According to its owner-pilot, Duncan Stewart, another of the typically ramble-tamble older guys you meet in this corner of the world, it’s the longest-serving Beaver in operation.

“We know how to build ’em in Canada,” Duncan says.

“We just don’t know how to sell ’em,” McCutcheon adds.

The put-in is a watery blip on the gums of B.C.’s flat central plateau, which provides access to the toothy Coast Range.

This is everyone’s first chance to size up the expedition party: nine people, including McCutcheon, stalwart Canadian river guide Mark Trueman, and Maranda Stopol, our safety and scout kayaker.

Trueman brings an irresistible enthusiasm to the proceedings with his homesteader beard, bashed-out front tooth (the result of an errant oar handle), and unstoppable drive. He’s the kind of guy who’d carry you, your broken leg, and your lacerated kidney out of the wilderness after fighting off a bear with a cedar branch, then apologize for not getting you to the doctor fast enough.

Maranda is an experienced river guide and kayaker from Idaho who’s currently a college student in B.C. She’ll paddle up and down the river assessing rapids ahead of our two rafts—18-foot, center-mounted, paddle-assist boats that weigh about 1,800 pounds each with gear.

I’ll be in Trueman’s raft, along with John and Cole Vangel, a father-son duo from Southern California. John is a fit corporate attorney. Cole is a beefy 20-year-old with long brown hair that hangs across his eyes. McCutcheon tells me he’s a physics prodigy at a university on the West Coast known for its super-bright student body.

In McCutcheon’s raft are Blair French and Paul Mick, a veteran paddler couple in their mid-thirties from Kelowna, the third-largest town in B.C. Paul is an ear, nose, and throat surgeon. Blair spent his childhood in Hope, B.C., where the immortal Rambo movie First Blood was shot.

The last figure is, without doubt, the most startling any of us have ever encountered on a high-consequences backcountry expedition.

Before we all got here, McCutcheon had walked me through the roster of paddlers, briefly mentioning “a wealthy widow who’s big on adventure trips.” I’d imagined one of those wiry dynamos in their mid-sixties who look primed to challenge the senior record for crossing the English Channel.

Instead, Jean Hollands dodders out of the Beaver, appearing not a day under 80, brittle as an egg, unsteady as the Indonesian stock market.

What this Hummel figurine is doing on a trip like this is anybody’s guess, but there’s no time for awkward questions. Once the whine of the Beaver’s engine has faded into the cloudless sky, we’re put to work rigging the boats.

“Say goodbye to civilization,” McCutcheon says.

We’re rafting through a flooded forest—one with a raging current going into it. Ever driven a minivan at 20 miles per hour through dense woods, then tossed the steering wheel out the window? Me neither, but I think this is what it would be like.

For the first couple of miles on day one, it feels like we’re paddling through a big-budget Molson’s ad. Snow-crested granite spires and bright blue glaciers provide the background scenery.

The first major challenge, about four miles from the put-in, is a Class V rapid dubbed Little Drop of Horrors. (It was christened by McCutcheon, who named most of the features on the river.) It’s a satanic shard of whitewater that combines everything in a policy writer’s nightmare—a steep, narrow plunge, barely submerged rocks, pushy rip currents, swirling eddies, frothing rapids, and the disposition of an injured wolverine.

McCutcheon’s boat goes first. It glides through the initial bumps before nose-diving into a yawning hole. The raft tacos into an almost perfect V before launching completely out of the water. In the rear, packed between gear boxes and dry bags as tightly as McCutcheon can wedge her, is Jean. Her head pitches forward, then jerks back in a way you normally associate with wide receivers getting nailed on pass routes across the middle.

With a lot of shouting from Canuck Norris—“Back-paddle! Back-paddle! Hold on! Hold the fuck on!”—he and the Blair-Paul paddle pros steady the raft, which disappears safely around a bend.

Our turn next. We bounce through the ferocious hole in good shape but get tossed violently by a standing wave and end up barreling headlong into a set of submerged logs on the far bank. While we’re high-centered atop the mini logjam, the river hits us broadside, twisting the raft perpendicular to the current. We start to tilt—five degrees, ten, fifteen—until the right side of the boat is sagging beneath the waterline.

“Left over! Left over! Left over!” Trueman shouts. Cole and I clamber atop stacks of gear like a pair of rheumatic chimps.

It works. With our weight shifted and Trueman and John leaning as far out from the edge as they can, the boat levels and we’re able to push off the logs. Hurling himself at his double oars, Trueman pivots the raft. We bounce off a rock, then careen backward into an alder thicket on the bank.

A flurry of branches rips across the boat at head level. My new “river ready” sunglasses snap in half. Cole takes the worst of it, picking up a set of bright red slashes across his cheek and neck. It’s a spooky moment. When those branches slap you at ramming speed, they can flip you out of the boat quick as a hiccup.

“Now that’s a classic class-five B.C. rapid!” Trueman shouts as John, Cole, and I struggle to regain equilibrium.

In camp, all the chatter focuses on our shared survival. Cole keeps talking about how he was totally in the water when we nearly capsized. John says he figured we were all goners when he saw his son’s water bottle floating downstream. For the first time, we interact as a group instead of a collection of strangers.

The campfire confessional leads to the Jean Story. Born in the UK, she survived the Blitz as a schoolgirl during World War II and emigrated to Canada in 1973. The slow pace of provincial Canadians shocked her on arrival, and it’s still a point of exasperation. Her first job was as a project director at an electronics firm, where she earned a reputation for being a hard-ass.

“One day another manager came up to me and said, ‘You know what you are, Jean?’ ” she tells us, somewhat proudly. “ ‘You’re a pushy limey broad!’

“I said, ‘Well, that’s exactly right. Thank you.’ ”

In Canada, Jean became a kayaker. Fanatical. The sport gave her an appreciation for nature she’d never had. Other than her two children, rivers became her passion.

Now, with a failing body but a strong spirit, she’s after “one last grand adventure.” The KK is it—she’s had this river in the back of her mind since she saw it on TV in the late 1990s. Like it or not, we’re to be her last accomplices and helpmeets.

Jean might be pushy, but she’s also clever. In the space of an hour, she’s gone from quietly resented appendage to the source of communal purpose. One and all seem united in seeing to it that this gritty old bird gets a final feather in her cap.

As we find out on day two, butchering through virgin wilderness isn’t just difficult. It’s often boring. At regular intervals, the KK is blocked by massive logjams and epic blowdowns. We’re forced to beach the rafts and watch from shore while McCutcheon clears the way, using a portable Stihl MH-170 chainsaw with a 16-inch bar.

For those unfamiliar with chainsaw specs, the MH-170 is the kind of tool you might deploy to prune branches from the apple tree in your backyard. McCutcheon somehow uses this humble implement to cut fallen century-old pine trees in half.

The process usually takes a couple of hours. While the group roasts in the sun on a river bank, McCutcheon wades into waist-deep currents or straps himself to the same log he’s cutting, buzzing away, precariously balanced above the menacing current.

“Brian’s great talent is the ability to muster people to follow him on these big, preposterous expeditions,” Trueman tells me while we watch. “He’s so charismatic, I have to check myself from time to time and remember to ask, ‘Is this really a good idea?’ ”

I ask why we’re encountering so many logjams.

“As a result of a late-season snowfall and a very hot spring, we’ve had extremely high water through here this year,” he says. “There are also thousands of weak trees along the shore diseased by pine beetles.”

Now, in an unseasonably hot summer, the water level is low, exposing obstacles, debris, and gravel bars you normally wouldn’t see.

“All the downed logs are forcing the river to divert, creating new channels everywhere,” Trueman says. “This is a completely different river from the one we last ran in 2012.”

“We’re going to run this stretch of rapids to where that fork is,” McCutcheon shouts above a roaring wave train. We’re standing on a sandbar listening and looking. “Right after it, we’re going to eddy out on the right bank.”

It’s around 1 P.M. With the morning’s chainsawing done, we’ve encountered a peculiar bend in the river—a wide, fast channel veering left off the main flow. There’s no way to tell where it leads.

“Whatever happens, do not miss that right bank eddy!” McCutcheon commands. “Do not go left. The results could be fatal to the expedition.”

We get back in the rafts. McCutcheon’s rocks up and down through the rapids and makes the right bank eddy without difficulty. Behind him, we set off with a confident stroke. Halfway through I sense that we’ve paddled too far left to make the eddy.

Trueman nearly pops a vein with his “Hard left!” bellowing. It doesn’t help. We boomerang off a downed log and careen sideways into the dreaded left channel, which quickly widens into something that looks like Louisiana swamp. Before, I hadn’t understood what McCutcheon was so freaked out about. Now I do. We’re rafting through a flooded forest—one with a raging current going into it. Ever driven a minivan at 20 miles per hour through dense woods, then tossed the steering wheel out the window? Me neither, but I think this is what it would be like.

Trueman pilots us into what looks like the safest spot—a small logjam pushed up against a stand of rotted trees. The idea is to get us stabilized on something before we crash into a tree, break a few limbs, and capsize.

But the log pile is no haven. As soon as we’ve lurched to a stop against it, the current turns us broadside and lifts us onto the logs. We’re wrapped on the pile; water begins bucketing into the raft.

The next few minutes are complicated and, for anyone interested in sizing up river-guide skills, remarkable. Trueman leaps into the current and secures the raft to a tree with a line. McCutcheon—who’s run after us like a boar through the dense woods—crawls over from the opposite shore, across the tops of more downed logs, and tosses us another line. Pulling the ropes against each, we stabilize the raft and eventually tie up on an almost nonexistent bank.

Unfortunately, there’s no feasible direction to go. Plowing forward in a 1,800-pound raft in whitewater through a flooded forest is suicide.

The dense, brushy woods along the riverbank are nearly impassable. No way to horse an 18-foot boat through them.

The only option looks to be the way we came in—which means backing out against current that a 125-horsepower motor would have trouble bucking. Four guys with plastic paddles have no chance fighting it. Instead, we’ll walk the boat upriver along the shallow bank.

It seems like an OK plan. Except that, in 30 minutes, we manage to coax the boat all of 20 yards. The decision is made to lighten the load and then retrieve it later. Stacking dozens of bags and boxes of gear in the swampy woods takes another hour.

Pulling the empty raft against the river is still a Fitzcarraldo effort. The bank is a vile thicket of alder, poplar, cedar, spruce, pine, cottonwood, willow, devil’s club, and berry bushes. Several times, Trueman and I drop into holes in the river. We sink up to our shoulders, frantically grasping for handfuls of slippery branches.

“This is not what I signed up for,” Cole grumbles. “Why are we doing this?”

“Don’t worry, we have a sat phone, we can always call in a helicopter,” John says, apparently forgetting that his son is an academic savant gifted with keen observational powers.

“Where the hell would a helicopter land? It can’t land here,” Cole shoots back.

A revised plan is formed. Instead of grinding all the way back upstream, we’ll draggle the raft another 20 yards or so upriver. This will put us in position to make a long-odds attempt to paddle across a shallow section. Make it and theoretically we’ll shoot through the flood zone into another mystery channel that appears to be flowing in the general direction of the main river.

I’ve paddled against a lot of tough currents in my life, but the desperation behind this upriver slog adds to my appreciation of the survival instinct. Or maybe I’m just good at taking orders, since Trueman is issuing them like the skipper on a Viking slaver.

“Fight it! Fight it!” he bellows “If we hit that logjam, push off it as hard as you can! Chuck, stick your paddle out. Break it on that sonofabitch if you have to!”

There’s no need for that. Trueman digs an oar deep into the water, finds a miracle seam in the current, and swoops us into the new channel. A quarter-mile later, we spot the rest of our party back on the main riverbank, waving to us like they just solved global warming.

After a five-hour detour through hell and high water, we’re back on the main river.

In places, the river is calm and we’re able to beach up for sandwiches, stretching, and conversation—during which things like the provenance of Cole’s overall skittishness are revealed.

At age 11, on his and John’s second father-son raft trip, on California’s Tuolumne River, Cole’s boat flipped in a rapid. He went into the water, lost contact with the craft, and ended up submerged for about 15 terrifying seconds.

Cole and John persevered, and Cole has grown to enjoy river trips, but that initial terror left a scar. The KK is the most ambitious expedition Cole and John have undertaken; the memory of the Tuolumne is always under the surface.

McCutcheon nods and confesses that, on previous trips through Little Drop of Horrors, his groups have flipped two rafts. Neither he nor Trueman were at the helm, but veteran, trusted guides were.

The worst capsized almost instantly, with six people going under, two for an uncomfortably long time. No one died or was seriously hurt, but there was a long moment when it was unclear who was coming up and who wasn’t.

“Don never ran another trip with us after that,” Brian tells the group. “He was a great guide, 15 years experience, perfect record. It wasn’t a guide error, but just the idea of being responsible for killing a group of people shook him up.”

After a couple of moments recovering his breath, Cole lifts his head, stares into my eyes, and, through long threads of drool, croaks, “No more whitewater. No more whitewater.” It’s a haunting epitaph for the trip.

Nobody Move, a rapid we do at the start of day three, is a monster Class V. Its primary features are a six-foot drop at the end of a rocky approach, followed by a 100-yard, boulder-strewn whitewater wave train that ends with a bone-clanging ten-foot drop into a flushing hole.

“This is one of the most dangerous parts of the river,” McCutcheon tells us as we inspect the run from atop a rock outcropping. “Strap your PFDs down tight.”

His group goes first. When the raft plunges into the bottom of the hole, it folds almost in half. Jean, sitting amid stacks of cargo in the rear right position, pitches forward, then whiplashes back like a crash dummy. Somehow she stays in the boat.

Our raft—the one that seems to be bearing the brunt of misfortune—sails through the main drop with unexpected ease.

“We’re getting the hang of this!” I shout at John as we click paddles high-five style. Behind us, though, there’s theater.

“We’ve got a swimmer! Cole’s in the water!” Trueman cries.

On most rapids, the fold and subsequent retraction of the rubber raft rocks the back more violently than the front. After our bow had barreled through Nobody Move, the stern kicked out of the water at a steep angle, pitching Cole from the boat like a beanbag.

“Back-paddle! Back-paddle!” Trueman yells.

It’s impossible to halt our momentum, but we go for it anyway. We can’t stop our descent, but if we can slow it, Cole will have a better chance of reaching the raft.

In a roil of whitewater, his head pops up 15 feet behind the boat. He keeps disappearing beneath the waterline, then bobbing up again. Each time he resurfaces, he coughs up water.

At the stern, rescue kit in hand, Trueman barks commands, steers the raft, and shouts encouragement to everybody. But the current is vicious. Caught in some invisible rip, Cole shoots like a Ping-Pong ball past Trueman’s outstretched paddle and goes underwater. When he resurfaces, he’s swirling next to my side of the raft.

Leaning out, I try to guide his hand onto the raft’s perimeter line. Our fingertips brush, but Cole is in a washing machine, and we can’t close the loop. He slips back into whitewater.

I flip my paddle around and extend the grip end as far as I can. Cole manages to grab the handle.

Got him! The adrenaline-fueled elation of this moment is as profound as anything I’ve experienced in the outdoors. I really believed this kid was going to drown.

But the fright has apparently sent every twitchy nerve in my body straight to my right arm. I yank way too hard, and Cole’s hand slips off the handle.

Two seconds from salvation, it’s as if some river monster has grabbed his ankle. He’s pulled straight down. I watch as his head goes under the raft, trapping him squarely beneath 1,800-plus pounds of rubber.

“He’ll come up, he’ll come up!” Trueman shouts.

Three seconds? Four? Five? Impossible to say. But when Cole pops back up—coughing, sputtering—he’s only a foot from me. I grab his PFD at the shoulder straps and hurl my body back into the boat. The wetsuit’s buoyancy works in Cole’s favor. He’s a big guy—190 pounds—but the top half of his body slides easily over the raft, and he lands in my lap like an exhausted halibut.

After a couple of moments coughing out water and recovering his breath, Cole lifts his head, stares into my eyes, and, through long threads of drool, croaks, “No more whitewater. No more whitewater.” It’s a haunting epitaph for the trip.

With the Cole episode leaving everyone unsettled, it seems like fate when, an hour later, our progress is halted again. Two or three hundred logs, assorted rocks, brush, and detritus have collected in a broad swath across a wide section of river. No one wants to say the word out loud, but we’re looking at a mother of a portage to get past this, and everybody knows it.

There’s no way Jean is walking across a wet logjam, so McCutcheon gets the show started by fireman-carrying her. Twice he skitters on the slick bark and nearly falls over. Jean’s body sags against his shoulders like a sack of rice.

“Forget the portage, if he drops her we’ll be dealing with a much more grave issue,” Blair says to me. “Like an actual grave.”

For five hours, we move a couple thousand pounds of equipment, piece by piece, from both boats. With no sure footing, everyone teeters along with the careful steps of a newborn fawn. We grind out an ad hoc path to a shallow side channel that skirts the logjam and dribbles its way back to the river.

Once the rafts have been completely emptied and derigged, it takes six people to heave each one across the logjam.

For all the physical exertion, the emotional setbacks are the biggest toll. For me, the hardest moment of the trip comes when Maranda, sent ahead to scout for camping spots, returns with the news that yet another logjam is blocking the river just downstream.

“Scariest scout of my life,” she adds helpfully. “Twilight closing in and bear and wolf tracks everywhere. Anyone have some repellent handy? I’ve never been so chewed up by mosquitoes.”

The reaction to Maranda’s “this ain’t over yet” bombshell is severe. At the end of the beastly portage, some of the group had posed for a photo, arms raised in triumph. By the looks on their faces now, you’d think everyone had just drawn the middle seat on a red-eye to Caracas. Even the irrepressible Trueman falls silent.

“If you guys are discussing a refund for the trip, fuck off!” McCutcheon shouts cheerfully from his raft, attempting to inject levity into the proceedings.

No one laughs. Not because they really want a refund, but because they’re too physically shot and crushed by disappointment to respond.

That night, after we set up camp on a gravel bar scouted by Maranda, McCutcheon wanders into the bushes with his sat phone. Thirty minutes later he gathers the troops.

“OK, here’s the plan,” he says. “A helicopter is gonna come in here tomorrow at noon to take us out of here.” There’s not even a whimper of resistance.

“We’ll fly up to camp at the Klinaklini Glacier and continue the trip from there,” McCutcheon says.

The airlift will effectively knock out the day-four itinerary—about 30 river miles—and drop us within a few hours, by paddle, to trip’s end at Knight Inlet. So far we’ve covered about 20 miles. In three days.

The helo pickup isn’t a rescue so much as an abdication. The B.C. wilderness is wild and mighty, and this time it has beaten us. Pushing ahead would be just short of lunacy.

“Of all the trips we’ve done on this river, this is by far the hardest,” Trueman tells me the next day while we wait for the distant whoomp of rotors. “This trip is on the verge of commercial viability. That’s why we’re the only ones who run it. And that’s because Brian has a huge sack. He’s willing to take the risks and take people out to do this stuff because he believes in it.”

It’s true, but even McCutcheon’s tolerance for risk has a limit.

“I’m dealing with a real liability issue here,” McCutcheon says. “Jesus Christ, Jean is 82! She told me she was 72. I have it in writing. When I saw her come doddering off the plane I thought, You’re 72? No goddamn way.”

When I ask Jean about this later, she allows that there may have been a mistake made on a personal information form, but she’d never intentionally mislead McCutcheon or anyone else about “such a silly thing.”

“I’m not worried about her suing me,” McCutcheon tells me on the river. “She’s a tough old Brit. She told me yesterday, ‘Brian, if I die out here, that’s OK.’ I said, ‘Jean, it’s not you I’m worried about. I’m worried about your family coming after me.’ ”

When all three guides are out of earshot, and the group is sitting around our piles of staged gear, I follow up on McCutcheon’s earlier joke and ask if anyone has actually considered asking for a refund.

“Not at all,” says Dr. Paul. “You understand the risks on a trip like this and assume things won’t go as planned. This is an expedition on a river no one’s seen in three years. Anyway, the trip isn’t over yet.”

Being taken off the river is frustrating. Everyone regrets not being able to complete a mission they’ve been prep-ping so long to do.

On another level, it’s a relief. Two days of hiking in the high alpine around our new camp at the terminal moraine of the Klinaklini Glacier is a tonic. An ocean of mountain peaks spreads across a limitless horizon. Between each one are pools of deep purple, neon blue, glacial-silt green, rusty copper—the mineral composition left behind by ancient glaciers gives each its unique hue.

On the last morning, Jean and I are the first paddlers up. McCutcheon is at the mess table making coffee.

“How are you this morning, Jean?” he asks.

“Well, my knees are a bit stiff, but otherwise I’m fine.”

“At your age, it’s a triumph just not waking up a stiff.”

Jean chuckles indulgently.

McCutcheon’s got a ton of these. What do you get when you cross an insomniac, a dyslexic, and a philosopher? A guy who lies awake all night wondering if there really is a dog.

Despite the recuperative days at the glacier, and McCutcheon’s jocular chatter, the grim-faced gang breaks camp for the final push as if preparing for an amphibious invasion.

Some of this has to do with the weather. The afternoon before, when it was 97 degrees, we’d swum beneath a waterfall. This morning it’s a marrow-thickening 46, and the sky looks like a piece of old meat.

Last day blues, I think. Trip’s almost over. No one wants to get back to work, overdue bills, the a-hole neighbors who keep letting their dog take a dump in my yard…

“Was that a raindrop?” Blair asks, squinting at the ashen sky.

Below the terminus of the Klinaklini Glacier, heavy wind and rain descend, and the river picks up speed. Furious rapids twist and boil.

Perhaps “boil” isn’t the best description of water that’s almost 100 percent glacial runoff. But it does burn when the first bathtub-size torrents of icy greetings slam you in the face.

“Wow, I’ve never seen the rapids so high here!” Trueman cries.

McCutcheon estimates the waves at 20 feet from crest to bottom. Our rafts are a little more than 18 feet long. We start riding the waves. If this sounds fun to you, it’s not.

These are the spookiest rapids yet. Not just because your body clenches against the nut-shriveling glacier water with each rude slap, but because the force actually pushes you backward. You have to lean into them to avoid being unseated.

“It’s all gradient,” McCutcheon explains. “Over eight kilometers, we’re dropping several hundred feet. And the water is full of silt with all the glacial rock flour pounding in there. That’s why it feels like a punch when it hits you.”

The guides call these “glacial facials” or “nasal douches.” I call it four hours of reliving the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge. This is how long we have to paddle to reach Knight Inlet for our rendezvous with the pickup boat, which at the moment is feeling more like a rescue vessel.

“Anyone feeling hypothermic?” Trueman asks.

We’re all busy suppressing the shivering instinct. Does that count?

Ahead of us, Jean is rammed down as far into the floor of the boat as McCutcheon can force her, popsicled into immobility. Her face is a death mask.

Before we’d set off this morning, she’d given Blair her e-mail address, along with the e-mail address of a friend of hers.

“That way, if you contact me and don’t get a reply, she can let you know if I’m dead or not,” she told him.

We round a bend to find McCutcheon’s boat beached. He’s lashing Maranda’s bright red kayak to the top of his raft. She stands beside him, her hands clenched in front of her like baby pterodactyl claws. In her kayak, she’s been taking the most punishment in the KK ice bath. She climbs into the back of our raft with a gutsy expression and forces her fingers around a paddle.

As we set off again, Trueman begins cackling like an incoherent hyena. John wants to know what’s so funny.

“This whole thing, this entire experience!” he shrieks, beard swinging in the breeze. “You didn’t think the KK was going to let us finish this trip without a slap on the back of the head, did you?”

We smell the ocean before we see it. A shift in the wind carries a briny tang over the top of the riverine air. Off our bow, a curious seal trains its glossy black eyes on the raft.

Through a mist of low clouds and beating rain, a blue and white speck bobs on the surface of the water. After hoisting aboard a group of frozen paddlers who have just endured three hours of Arctic-blast conditions, the first thing the boat’s captain thinks to do is reach into his cooler and shove a cold beer into each of our frozen paws.

We all make polite efforts to partake, but by the time anyone can get halfway through a can, we’ve fallen asleep in the boat’s warm, steamy cabin.

“I’m the last expedition company running multi-day river trips in B.C.,” McCutcheon tells me later. “I’m the youngest of the old guys who do this stuff. This place is one of the last bastions of this type of trip.”

After the KK group’s goodbye on the public dock in Vancouver Island’s Port McNeill, I spend a couple of weeks driving around B.C. On the way home, I detour to McCutcheon’s Bear Camp headquarters near Chilko Lake to return some gear.

I’m lucky to find him in a rare sitting mood.

“Day river-rafting has become so orchestrated, it’s like Disneyland,” he says, hitting a now familiar theme. “Bus leaves at 8:30. Stop for snack at 10:30. Lunch at 12:30. Back by 4 p.m.”

Given his pessimism about the adventure market, I ask about the viability of future runs down the Klinaklini.

“The reality is that this was not a profitable trip,” he says. “This KK trip was definitely the most challenging we’ve done.”

Did he think twice about having us airlifted out of trouble?

“The concern I had was, the way our luck had been going, it’s almost for certain we’d have needed it at some point. The province has been sequestering helis for forest fires, so you take the machine when you can get it. That was my thinking.”

Inevitably, the talk turns to Jean.

“I gotta admit, it’s pretty ballsy to come out here at her age,” McCutcheon says. “From my perspective it’s terrifying, but it’s also pretty cool.

“She said as much to me afterward. She said, ‘Brian, it’s not my job anymore to worry about how old I am.’ ”

Jean has already sent an e-mail to the group, so we open that up. It’s a witty and touching thank-you note that ends on a line that’s as apt an explanation for running this river as any of us are likely to write.

“It was the best trip (expedition? suicide mission?) of my life,” she writes. “But the best part is that when I returned home, my piled-up mail included a missive from UK Pensions asking me to prove that I was still alive.… Was there any doubt?”

Chuck Thompson is the author of five books, including Smile When You’re Lying and Better Off Without ’Em.