A MOMENT AGO the world was a sunny, happy place, full of giant herons gliding like pterodactyls on desert winds and schools of uncountable gar and bass swimming in turquoise pools so clear you could see crawfish walking on the bottom in ten feet of water. A place of exquisitely tortured limestone, river boulders the size of houses, humped black canyons framing pale autumn skies.

Lower Pecos

No more than 40 people run the Lower Pecos each year.

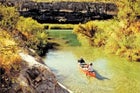

No more than 40 people run the Lower Pecos each year.Emerald waters

Pristine emerald waters on take-out day

Pristine emerald waters on take-out daySide channel

Meandering through a side channel

Meandering through a side channelLargemouth bass

Landing largemouth bass

Landing largemouth bassLining

Lining through a shallow section

Lining through a shallow sectionStuck

Scene from the disaster

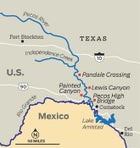

Scene from the disasterRegional map

Regional map

Regional mapLower Pecos

Lower Pecos map

Lower Pecos mapBut that is all gone now.

In its place is an entirely different reality familiar to civilized people who have taken small boats into wild rivers. Four of us, in two canoes, have entered a stretch of whitewater that we have grossly underestimated. Only one boat has made it through. The other is pinned sideways on a rock, transformed suddenly from a reasonably efficient craft into a fixed part of the river, a small waterfall with tons of water now cascading over it. The 16-foot-9-inch polyethylene Old Town begins, ominously, to bend along its thwarts. There is no budging it. Not even a millimeter.

While watching our expedition mates cling to their canoe, Bill, my sternman, and I now have the leisure to contemplate this predicament.

We would seem to have only one option, and it is not encouraging: abandon the canoe and all of its gear, empty our craft of most of its equipment, and run the remaining rapids with four men in one boat. There is really no other way into or out of these steep rock canyons. Paddlers with worse problems—like severe injuries or the loss of their vessels—are rescued by Border Patrol helicopters, if agents are not otherwise occupied chasing drug runners, coyotes, and other border crossers who tend to crop up in this part of the world.

Our problem lies in the fact that we are, in continental American terms, in the middle of nowhere. More precisely, we are on the Lower Pecos River, in West Texas. You have probably not heard of this particular stretch of the Pecos, the final 60 miles of which runs down to join the Rio Grande on the Mexican border near the town of Del Rio. Most Texans are aware of it only as they encounter it from the Pecos High Bridge on Route 90, where the river, widening before it joins the Rio Grande at Lake Amistad, cuts through a breathtaking limestone canyon. Travelers get out of their cars and take pictures, stunned by one of the most spectacular views in the desiccated wilds of West Texas, wondering where this wide, muscular desert river has suddenly materialized from. And then they move on to San Antonio or Los Angeles or wherever they are headed. Most people who do know the Pecos River know its New Mexican section, 800 miles or more upstream, which originates in the snowy upper elevations of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. This is not that river, in any sense, as you will see. No more than 40 people run the Lower Pecos each year. In many years, far fewer.

There are good reasons for this. The Lower Pecos is surrounded on all sides by private land and is inaccessible to weekend enthusiasts and other river runners who do not have a lot of time on their hands. You are allowed to put your boat in at exactly one place, a tiny cluster of cabins known as Pandale Crossing, and take it out at exactly one place, the high bridge on Route 90—and there are 60 difficult river miles and seven days of paddling in between. There are hardly any people or towns out in this rough, empty stretch of Chihuahuan desert. On nighttime satellite maps, this part of West Texas is one of the darkest areas in the lower 48. There are no public lands here, no national parks or national forests or friendly rangers, no park roads or convenient facilities. The river pierces country dominated by enormous ranches—20,000- and 30,000-acre spreads—that make it a sort of private wilderness, and all the more wild for it. It is a place, alternately, of cataclysmic floods and extreme droughts.

For all its obscurity, the Lower Pecos flows through one of the loveliest and most pristine landscapes in America. Spring-fed and limestone-bottomed, the river has a clarity matched only by its wild tropical color schemes, which would remind you of a Corona beer commercial except that the colors are far more varied. It is both a whitewater river, with dozens of rapids from Class I through Class IV, and a giant aquarium—jammed with spotted gar, catfish, perch, bluegill, and carp—where you can watch a largemouth bass wheel, rise, and hit your fly. The country around it is a sort of museum of Native American history, home to one of the greatest concentrations of ancient rock art in America.

And so it is surprising that, out beyond the 100th meridian, where vast commercial cultures have arisen to service affluent Americans desperate for a run down big, remote, mythic rivers, no one knows the Lower Pecos. Our predicament in the rapids is relatively simple, in one sense: we’re the only ones here.

OUR TRIP BEGAN on the first day of November, in bone-dry, brilliantly clear 80-degree air, the sort of Texas weather that makes you glad you are alive and makes people from Milwaukee and Chicago wish they lived somewhere else. The cruel summer heat—110 and above—had gone away, and the northers had not started to blow yet.

We had driven 250 miles west from Austin, through the limestone canyonlands and live oak savannas of the Hill Country, the land a young Lyndon Johnson civilized with hydroelectric power. This is in fact where the Big West begins. As you pass the town of Junction and cross the winding Llano River, you realize, looking at the high mesas and rock outcroppings and ashe juniper forests, that you have finally left all of that forested trans-Mississippi land behind. Now we were in something completely other, a spectacular collision of three ecologies: Hill Country limestone river bottoms, Chihuahuan Desert uplands, and what botanists call Tamaulipan thorn scrub.

Who are we? A motley assemblage of middle-aged men, all looking for a bragging-rights adventure in the great American West. Maybe that sounds vainglorious. But middle-aged men tend to think that way. The clock is ticking down, and for most of us the remoteness of this expedition will test the limits of our abilities. I am 57 years old. There is my friend Jeff, 54, an investment banker from Dallas specializing in bankruptcy, with whom I used to drink inordinate amounts of Scotch and play Jerry Jeff Walker songs on guitar until 5 a.m. before going off to work, bleary-eyed, at a bank in Cleveland. There is Bill, also 54, my paddling buddy from Austin, a chiropractor with great medical knowledge and an obsession with outdoor gear, with whom I have kayaked many Class III rivers in Texas and the Northwest. And then there is Paolo, 41, our photographer. He is here for professional reasons. Paolo scales thousand-foot rock cliffs and ice-climbs in temperatures 30 below zero. He has swam with sharks and biked a thousand miles through Mexico. Paolo is not like us.

Our group has descended rivers before but nothing like the Pecos, which has a reputation for being murderous on marine hardware. In 1590, the Spanish explorer Gaspar Castaño de Sosa and his expedition tried in vain for two weeks to find a place to cross the river and were thwarted by the rough and difficult country with “many sharp rocks and ravines.” He also noted that the rock had managed to ruin 25 dozen horseshoes. In the sole guidebook to this section (The Lower Pecos River, by Louis F. Aulbach and Jack Richardson, 2008), the Pecos is described as a place where your boat is in almost constant collision with rock—limestone that is pitted and harshly abrasive and that chews the vinyl off the bottoms of boats. Canoes are routinely pinned or broken. Indeed, after calling a dozen outfitters, the only one who would rent us canoes for the Pecos was a guide we knew on the Devils River, another immaculate limestone-bottomed stream in West Texas. What he gave us—severely battered and cracked Old Towns with keels that had been re-epoxied so many times they looked like abstract art—seemed like a bad joke.

We traveled an hour north from the border town of Comstock to the launch site at Pandale with our shuttle driver, Emilio, who charges $325 for the drop-off and the pickup by boat at the other end. There is no bridge at Pandale, just a place where a bridge once was and a road that can be crossed only at low water. We stuffed the canoes well beyond the gunwales with drybags and coolers and water and fishing gear, planning to be out six nights and seven days camping along the river’s banks. Landowners here are tolerant of this, partly because they know how murderously difficult it would be to climb out of the canyon and trespass any further. As we launched, the river was running at 180 cubic feet per second (cfs), slightly below its average, which meant we would be encountering a good deal of shallow water and many sets of rocky rapids, especially in the first 20 miles.

We were soon careering down the first set and leaving the known world behind. One of the best things about the Pecos is its intimacy. The river is generally quite narrow, usually only 20 to 30 yards wide, bounded on both sides by ocher-colored limestone cliffs with deep black stains. As we moved downstream, there was a clear sense of descending as the canyon walls loomed higher. The river itself becomes much deeper, stronger, colder. The farther down we went, the more we seemed to be in the canyon’s close embrace, enfolded by it and contained within it as though in some sort of bejeweled box amid the dun-colored hills, canyons, and mesas of the open desert.

There is another side to this intimacy, too. On the Lower Pecos, at these flow levels, we are often less on the river than in it.

Jeff and Paolo were in one boat, Bill and I in the other. As we plunged into our first sets of rapids, we were surrounded by thickets of cane, which grow 15 to 20 feet high and create dark labyrinths in the river. The effect was a sort of Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride as we whooshed through five-foot-wide chutes cloaked by cane thickets so dense we couldn’t see through them. This was complicated by the fact that our boat teams were often working at cross-purposes, the bowmen (Jeff and me) screaming “Right, right, right!” while the men in the stern, distracted by the roar of the river, steered resolutely left, directly into whatever it was that the bowmen wanted them to avoid. Two- and three-foot standing waves broke regularly over the bows, soaking us and filling the already overladen boats with water. This lent a certain comic aspect to our descent.

“I was trying to point that rock out to you,” I said to Bill, after we had hit one with a sickening thud and shipped on enough water to turn our canoe, aerodynamically speaking, into something more like a waterborne sofa.

“I still haven’t seen it,” Bill replied placidly. “Maybe we need to work on hand signals.”

There are other forms of intimacy with this river. Rapids that we couldn’t run had to be lined, an often difficult process using bow and stern lines to lower your gear-stuffed canoe through rapids. Throughout that first day and into the second, we were often out of our boats, hauling them over the shallow river bottom. In one notorious four-mile section, known as the Flutes, we dragged our boats over thousands of peculiar sculpted rock formations that sat just below the surface. Bill and I quickly discovered that our canoe leaked, and each time we lugged its overstuffed hull across all that rough limestone, we imagined the cracks getting bigger and bigger. We tried to patch them with duct tape where we could.

But these are minor inconveniences. For every rapid we had to line or drag, there were ten that were both rollicking and relatively easy to run. On one occasion, a few miles in, we found ourselves in an ever-darkening, cane-bracketed chute that became, alarmingly, narrower and narrower. Four feet wide, three feet wide, two feet… A dead end would have been a small disaster, a sort of blind alley with no way out and the straining effect that all paddlers fear. Bill and I lost sight of Jeff and Paolo, who’d somehow found the main channel. The cane closed around us and the canoe began to turn sideways as the two of us, truly alarmed and cursing both the cane and the rather large spiders that were now running rampant over our faces and the boat, prepared to bail out. Just at that moment, we suddenly, and unaccountably, punched through the brush into the main channel.

“Hey, where’d you guys go?” yelled Paolo, a hundred yards downriver.

“To the land of the cane spiders,” Bill replied. “Sorry you guys missed it.”

THAT THE LOWER PECOS exists at all is a small miracle. Like so many other western rivers, the Pecos was the victim, from the late 19th to the mid-20th century, of a series of grand and misbegotten attempts to harness it, dam it, and use its water to create the sort of irrigated paradise that the usual assortment of eastern land companies, tubercular millionaires, European financiers, railroad touts, reclamationists, industrial magnates, mining capitalists, and dry-land dreamers believed the West would become. They were wrong, of course, but it did not stop them, collectively, from damming up a great river.

The Pecos in its legendary, historic state was a waterway that flowed deep and strong from its origins in the mountains, through eastern New Mexico and West Texas, joining the Rio Grande—a river it roughly parallels—on the Mexican border. It happened to cross the Southwest precisely at the point where the land turned from simply harsh frontier into a gigantic, canyon-scarred, and lethal landscape that all westering settlers feared. The Spanish considered the country of the Lower Pecos difficult if not impassable. The phrase west of the Pecos refers not only to the folkloric character Judge Roy Bean (“the law west of the Pecos”; see Newman, Paul), who operated out of the town of Langtry, but also and more tellingly to the great emptiness that lies just beyond it, a rugged, dry, and mountainous land that would kill you with thirst or starvation or, if you were less fortunate, by torture and evisceration at the hands of Comanches and Apaches. For most of the 19th century, the Pecos was one of those western rivers that, whether you were driving cattle, running a wagon train, marching blue-coated soldiers, or riding with a Comanche war party, you had to cross. It was the gateway to the Southwest, to the great lands of the old Spanish empire, to California. The river was famous for its swift currents and its quicksand, and if you made it through the most logical ford—the low-water Horsehead Crossing, between present-day Odessa and Fort Stockton—you considered yourself lucky.

All that changed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The agent of that change was water. Five dams were built between 1888 and 1988, first by private firms and then by the federal government, to capture the Pecos’s water and divert it to agricultural use. The most famous and massive of these irrigation schemes, the Carlsbad Project, happened in and around the town of Carlsbad, in the southeastern corner of New Mexico. Water was impounded and diverted in a series of canals and pipes to the barren lands around the river, turning them into fertile fields. If you fly over the central and southern parts of eastern New Mexico today, you can see the effect: a belt of bright green land spreading like a stain into the desert.

Almost all of the river’s water was impounded by New Mexico, but what that state did not take, the Texans did. At Red Bluff Dam, just south of the state line, Texas impounded most of what was left of the Pecos, leaving a small, alkaline, salt-cedar-choked stream to make its way pathetically south toward the Rio Grande. This is the way many people think of that river: dammed and tamed in New Mexico, a trickle in Texas. If you saw what emerged from Red Bluff Dam, you would consider the Pecos a dead river, or nearly dead, anyway, certainly compared with what it used to be—one of many victims of the reclamation craze.

But as the river cuts southward through deepening limestone canyons and ever more inaccessible land, something remarkable happens, unseen by most people. Liberated by the sheer ruggedness of its country, the Pecos rises again, replenished by a sudden and enormous flow of crystal-clear water that enters from spring-fed creeks. The biggest of these is Independence Creek; fed by some of the largest springs in the state—including Caroline Spring, which pumps 3,000 to 5,000 gallons a minute—it joins the river just south of Interstate 10.

The effect of all this on the attenuated Pecos is astonishing. Suddenly, and with a whoosh of brilliantly clear water, which my companions and I can feel as we go downriver, a great western river is reborn. The sheer volume of what is being pumped into it—an additional 40 percent of the Pecos’s flow—defeats all the attempts, upriver, to contain and reduce it. Thus re-created, the river runs gloriously through its cloistering canyons to the Mexico border. If it is a waterway of great beauty—and it truly is—it is also unforgiving, the scene of some of the worst flash floods in America, draining such a huge watershed via Independence Creek that it is not unheard of for paddlers to be hit with a 20-foot wall of water under blue skies. In 2007, water-flow levels hit 25,000 cfs in canyons where the norm is 200. At its record high in 1954, the Pecos hit 948,000 cfs and drowned several people on its shores.

ON OUR SECOND NIGHT OUT, we pull in to the campsite at Everett Springs, exhausted by a ten-mile run that involved a good deal of complete immersion in the Pecos: wading, pulling, dodging strainers. The place is a sculpted, smooth grotto. On one side is a steep rock wall, on the other a little Eden of willow, oak, mesquite, cedar, chinaberry, and mountain laurel. At least eight springs gush from the steep rock wall. One of them is wonderfully warm. Another, emerging ten feet up the rock face, is enveloped in an enormous, lush beard of moss and ferns and lichens. I stand beneath it, feeling the water run over my body. The springs flow down our little canyon, burbling in a three-foot-wide, two-foot-deep stream through clear pools in the curvilinear stone.

“How would you rate this camp?” I ask my friends as we’re setting up the tents.

“Top three—ever,” Jeff and Bill both say. I say top two, maybe the best ever.

Paolo says nothing at first. I assume this is because, for all I know, he has probably already run the wildest river in the Gobi Desert. “Not bad,” he finally offers. “Really pretty amazingly nice.” (Later, at Painted Canyon, he will up this to “crazy beautiful.”)

We slip into what will become our routine. Jeff and Paolo take off with their fly rods, ribbing each other about who is catching the most, or the biggest, fish. (“Oh, look,” Paolo says, “Jeff has caught some giant bluegills,” meanwhile showing off his splendid green-black haul of largemouth bass.) Bill occupies himself with tent gear and water purifiers. I busy myself with setting up the fire. Later we make fish tacos with fancy tartar sauce we have brought, spotting armadillos, a javelina, and white-tailed deer as we eat.

We fall asleep to the murmur of the spring, or at least we try to. Jeff, as it turns out, snores loudly—it sounds something like the London Symphony Orchestra tuning up—so Paolo has decided to sleep outside. He is not entirely certain this is a good idea.

“What do you think there is out here?” he asks, gazing at the raw desert all around us.

“Snakes, black widows, tarantulas, scorpions, centipedes,” I begin to answer.

“Centipedes!” says Jeff from inside his tent. Apparently, he is not fond of them.

“Oh, that’s very encouraging,” says Paolo. Nonetheless he sleeps outside, that night and for the rest of the trip.

At each of our campsites, signs that human beings lived in these limestone caves and overhangs for thousands of years are everywhere. There are mortar holes, seams of worked flint, and strange incisions in the rock made in parallel lines. There are also hundreds of rock paintings. With a little help from an informed source, we find one of them. About halfway down the river, we pull the canoes out onto a bleached gravel bar; Jeff uses his machete to hack through 50 feet of river cane, and we follow him into a small side canyon that was invisible from upstream. We scramble up a steep slope, at the top of which is a 100-foot-long rock shelter. Running for most of its length is a brilliantly preserved 4,500-year-old painting, depicting in black, red, and yellow pigments what looks like a collision of the real and magical worlds. In the middle stands a black shaman, five feet high. He is elongated, ornamented and surrounded by sinuous, snaking lines. To each side of him, lesser beings proliferate; you can see spears and clubs, dead people. There are arcs and squiggles that seem to define and limit power; there are odd flying creatures. On the far left is a plump panther, prompting the name by which this cave painting is sometimes known: “Piggy Panther.” The painting manages to be surrealistic, primitive, abstract, and completely real. It’s like stumbling upon a Vermeer while walking in the woods.

The next day we find petroglyphs. We make camp at Lewis Canyon, on yet another tiered, sheltered white limestone shelf, climb to the top of the cliffs, and find ourselves standing on two full acres of rock art—carvings on a flat limestone surface. There are hundreds of glyphs, many of them pure abstractions. There are handprints and bear paws and swirls that look like targets; there are carvings of atlatls everywhere.

After dinner, we apportion our whiskey—a few ounces apiece—and lie back and gaze at one of those startlingly clear star shows you get only in the darkest parts of the electrosphere. Bill, in his wisdom, offers an elegantly simple explanation for what we have just seen: “They were just drawing what they saw,” he says, “and you have to believe they were seeing the same thing we are seeing. They were drawing the gods of the night sky.”

IN OUR PLANNING for the trip, we made one miscalculation, and it was a serious one. By day four we are running out of water. This may seem odd, surrounded as we are by a diamond-clear river. But that’s one of the prices we pay for dams. South of Red Bluff Dam, the river flows over alkaline beds, which means that even though we cannot taste them or see them, the river is full of alkali salts. The water can make you sick. Bill’s high-tech water purifiers do not work against this.

In the lower part of the river, there is exactly one freshwater source, known as Chinaberry Spring. As we come within range of it we have exhausted our water. Chinaberry is no ordinary spring, in the sense that it does not emerge from a rock in an easily visible place. Bill has tried to plot its location using his GPS and topographical maps, but he can only approximate, and our only tangible clues to its location in a 60-mile run through an enormous desert are (1) a chinaberry tree, of which there are tens of thousands, and (2) as Aulbach’s guidebook describes it, a sound of “a gurgle of running water” back in the cane. That’s all.

Amazingly, Jeff and Paolo both manage to identify the tree. Then, probing along the cane thicket at the river’s edge, they hear a very faint sound of dripping. But the sound is coming from deep inside the cane. We all pull our boats up, and what follows is that peculiar existential moment when someone has to be chosen to do the dirty work. Jeff, the owner of a machete that has done yeoman work on our trip, volunteers. “How many centipedes do you think are in there?” he asks. (Even though we have seen only one centipede and have only a vague idea of what one could do to you, they provide a sort of thematic unity to the trip.)

“Probably not more than a couple thousand,” I answer cheerfully. “Your main worry is probably snakes.”

And so Jeff gets out, wades through the muck, and begins to hack his way through dense thicket until he has completely vanished from sight. The rest of us wait, anxiously, in our boats. Above us looms a 300-foot cliff.

“You guys are going to owe me big,” comes the voice. He is now up to his waist in mud and in almost complete darkness.

“Can you see it?” I ask, not really believing for a moment that he can.

“Yes,” he says at last. “Yes, I can see it.”

What he sees is the sort of trickle that would be barely enough to brush your teeth, and it is bubbling out of the mud at the base of the cane, about a foot above river level. It’s a sort of miracle. Jeff has to whack away the mud and the cane to even get to it. He fills a five-gallon jug with the water and emerges, and now it’s my turn to fill the second jug. I wade into the muddy darkness and behold the tiny trickle. I fill the rest of the jugs while Paolo attempts to shoot this weird, dark endeavor. But we have our water.

IN THE LAST TWO DAYS of the trip, the river bears little resemblance to the one we started out on. Everything is bigger, from the water, which is now often 20 feet deep, to the black cliffs, which rise 200 to 300 feet above us. The current is much more powerful here. We seem to be almost constantly in strong rapids that demand our full attention. In Waterfall Rapid, a Class III with a nasty hole, we decide to line the boats—mainly because the prospect of losing one or both of them is starting to seem less and less desirable. Bill and I go first. It’s an immediate disaster. The boat flips, smashes into a rock, rolls over, then labors on its side, like something dying, through the rest of the rapids. This places Paolo in a professional dilemma. He is just downstream, shooting this marvelous scene of canoeing gone wrong. Should he do his job or save the boat? He curses, shoots a few more frames, then hustles down the rock bank after the boat.

Now it’s Jeff and Paolo’s turn.

“What do you think went wrong?” Jeff asks his partner.

“Operator error,” says Paolo. “This is a piece of cake.”

Moments later their boat is fully capsized and engulfed in whitewater. For the next hour we retrieve gear and bail and repack the boats. Our last night is spent at the most beautiful place we’ve seen yet: Painted Canyon, on a high limestone shelf at the head of a long Class III rapid. Here the river has carved a small lagoon with 30-foot walls and brilliantly green water. The lagoon is also full of fish. The spotted gar are three feet in length, with long snouts that make them look like barracuda. We swim, diving deep into the emerald pools. We eat catfish and bass and bluegill, marinated in olive oil, garlic, and salt and pepper and then pan-fried. We go to sleep in warm desert thermals and wake to a perfectly still morning in what seems to be the very heart of the American West, a place as it once was, when Stone Age hunter-gatherers ground their food in the rock holes we see all around us. I am exhausted; I ache and have bruises and cuts all over my legs. But that night as I watch the stars, I have an odd momentary realization that I’m not thinking about anything but those stars. Everything else has disappeared.

The end looms. Six miles downstream we are supposed to meet Emilio and a friend, who will tow us out the remaining ten miles to the take-out at Pecos High Bridge. We were sternly warned about these final miles, where the river begins to join Lake Amistad, created by the damming of the Rio Grande. Here the wind can blow 40 miles per hour for days at time, a southerly blast from Mexico so strong that you cannot paddle against it. It can be a cruel and bitter ending to a good trip.

It’s in this last stretch of river before our meeting spot that we enter something called Big Rock Rapid, where we pin the canoe. Pinning is a unique, unsettling experience. It does not even seem quite plausible. One moment you’re paddling a relatively maneuverable boat; the next you’re contemplating a sunken, immovable piece of wreckage. We spend a good hour taking everything out of the canoe, watching for signs that it’s going to break in half. Somehow it holds. Once it’s empty, though, it seems just as stuck under all that water as it did with 300 pounds of gear in it. At this moment, spurred by our mishap, I realize, for the first time really, how much can go wrong, even on a doable river like the Lower Pecos—a notion that probably wouldn’t have occurred to me at all at the age of 30 or even 40 but very definitely does at 57. The Pecos at this water level is not a terribly dangerous river. And yet in these wilds, injury or even death can be quite a casual thing: a foot stuck under a rock in high rushing water, a slip on one of the rock cliffs we climbed, a rattlesnake bite, or just a garden-variety heart attack. I silently vow never to run this river again with fewer than four boats.

Paolo, of course, has the solution. He tells us all to pull upward on the upstream gunwale, and miraculously the boat buoys up and floats off, swamped but intact, beyond the rocks, to the pools at the bottom of the rapid.

All that remains is our tow out. Emilio and his friend meet us in an old pontoon boat with an even older outboard motor. We pile the gear on, strap the canoes alongside, then motor for two and a half hours into a stiff headwind. Our destination is that magnificent Route 90 bridge, the one with the stunning view of the Pecos River Gorge, where people take pictures and wonder, as I used to, where in the hell that river came from. And it is gratifying that, after a week on the water, I finally know the answer.