“Damn! That was a bow shot! I knew I shoulda brought my bow.” Jim Cummings, our guide, had locked eyes with a fat, antlered deer munching sagebrush on the river’s edge. Armed only with a canoe paddle, Jim watched as the animal traipsed uphill, white tail bobbing. “Old Lewis and Clark would’ve had that buck on a spit by now,” he said as we paddled on.

lewis and clark, missouri river

Unlike Jim, a native Montanan with a Yosemite Sam mustache and a permanent cheek-bulge of Skoal, I’d never thought of a deer as potential dinner. Like many East Coasters, I was raised on a Hollywood version of the West. My image of Lewis and Clark was tainted early by the 1955 film The Far Horizons, in which Charlton Heston played William Clark against Fred MacMurray’s wussy Meriwether Lewis. Despite this handicapped historical interpretation, the 2004–2006 bicentennial of Lewis and Clark’s journey gave me the chance to experience the real deal.

When the two men left Camp Dubois, near St. Louis, in May 1804, about two-thirds of Americans lived within 50 miles of the Atlantic. The West, for them, was a mysterious Land Before Time, home to prehistoric mammoths and lost tribes of blue-eyed Welshmen. President Jefferson had just bought a sizable chunk of this never-never land from the French for about three cents an acre—the Louisiana Purchase cost $15 million—and wanted to know what kind of deal he’d gotten. And so Jefferson charged his assistant Lewis, the buff former Army captain Clark, and their 40-plus-man Corps of Discovery with a daunting mission: to locate a direct, navigable passage from the Mississippi to the Pacific.

Like Lewis and Clark, I headed west with grand ambitions. I was determined to see a slice of America and tap into the innocent wonder that gushes from the pages of the duo’s expedition journals. I wanted to have the experience without the “help” of interpretive markers, scenic overlooks, and commemorative Lewis and Clark candy bars. (Yes, they exist.) And because the majority of their epic unfolded along the course of the Missouri River, a paddling trip seemed the way to go.

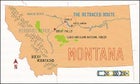

I talked my brother Joe into coming along to play Lewis to my Clark. Jim’s buddy Dan, a coffee buyer from Seattle, rounded out our four-man corps. We paddled the Hummer of canoes, a 34-foot replica of the skin-over-frame boats used by 19th-century fur trappers. Our four-day outing would take us along 50 miles of Montana’s Upper Missouri River, from Virgelle to Judith Landing, the same stretch that Lewis and Clark covered between May 29 and June 1, 1805.

We put in, our first day, by an old ferry landing in Virgelle (population two) and headed east downriver—opposite the direction the Corps of Discovery went. “Only a fool would go upriver in a canoe if he didn’t have to,” Jim stated matter-of-factly when I looked confused. In an unfortunate Ken Burns moment, I mused aloud about heading east toward the past, rather than toward America’s future, as Lewis and Clark had done. “Just paddle,” said Jim, spitting tobacco juice into the muddy current.

After a half-day of easy paddling, we set up our camp on a low ridge above Little Sandy Creek, one of the many well-spaced campsites along the river designated by the Bureau of Land Management. Lewis and Clark passed this spot on June 1, 1805, as they made their way toward the confluence of the Missouri and the Marias, where they were to face a crucial decision about which river to take west. Jim shared his philosophy on tracking Lewis and Clark that night over a blazing fire and bourbon.

“Folks come downriver expecting to see the warm embers from Lewis and Clark’s fires. I tell ’em this isn’t Disney World, so they’re gonna have to use a little more imagination.” He fueled ours by reading aloud some of his favorite journal passages, like Lewis’s description upon seeing the Great Falls of the Missouri: “I wished … that I might be enabled to give to the enlightened world some just idea of this truly magnificent and sublimely grand object which has, from the commencement of time, been concealed from the view of civilized man.”

As we glided along, mile after placid mile, it was hard to imagine this as the same section of river where Lewis, as he vividly described, struggled around rocky points (“the water drives with great force”) and where safe passage required “much labor and infinite risk.” For us it was a cakewalk, especially with the current in our favor. But we soon learned that the old Missouri still has a few tricks up its sleeve.

After enduring a night of lashing rain coupled with chinook winds, we broke camp at Eagle Creek, the Corps’s May 31, 1805, campsite, and paddled right into a 40-mile-per-hour headwind. “There’s sheep walkin’ today,” yelled Jim from the stern. As I scanned the banks for livestock, Jim explained that it was just an old river saying for the whitecaps on the water.

At a sharp bend in the river, water plumes lashed our faces, threatening to spin our canoe around. After an hour of muscle-burning paddling, we pulled ashore. Using towropes and sloshing through knee-deep water, we guided the canoe around the bend—finally—and into calmer waters. This technique, known as cordelling, was an almost daily penance for the Corps as they struggled upriver against a much wilder Missouri.

Along with enduring a hint of the hardship the Corps experienced, we were awed by some of the same natural wonders that had inspired them. For 25 twisty miles, the bizarre sandstone formations of the White Cliffs loomed over us, resembling melted gargoyles. And at several points on the river we stopped, disembarked, and hiked through slot canyons with names like Butcherknife Coulee. Up on a windblown ridge, we traced circle after circle of weathered stones, the lonely remnants of a Native American tepee village.

The highs and lows of our trip offered no comparison to those experienced by Lewis and Clark. They gnawed on greasy beaver tail; we savored cornmeal-encrusted salmon. They were allotted a gill (four ounces) of “ardent spirits” per man daily; we allotted ourselves, well, more. They suffered from boils, dysentery, and dislocated bones; I broke a nail opening a beer can.

In the end, though, my hopes of experiencing Lewis and Clark’s West were almost realized. The Missouri River scenery has lost none of its beauty, but we’ve sadly lost the perspective of innocence. It’s impossible to tap into the sense of danger and imminent discovery that must have gripped those pioneers.

Armed with guidebooks and maps, my back to the Pacific Ocean, I mostly knew what was coming and how I might feel once I arrived there. And I couldn’t escape the hard fact that, in even the deepest slot canyon, I was still within 70 miles or so of the nearest Big Mac.

The westward journey of the Corps reached its ultimate goal in November 1805, when the weary travelers finally came within sight of the Pacific. Clark summed up his relief succinctly: “O! the joy.” With no ocean at the end of our own trail, we sought our joy at the bottom of a glass in the Sip-N-Dip Lounge, fittingly located just upstairs from Clark and Lewie’s Pub & Grill in the city of Great Falls. While a team of well-fed, sequined “mermaids” frolicked in a pool tank situated behind the retro tiki bar, we toasted the intrepid group of explorers who had unwittingly brought us to this point.

“Just think,” I said, waving to a particularly shimmery swimming mermaid. “If it weren’t for old Lewis and Clark, none of this would have been possible.

Millions of Americans are expected to hit the Lewis and Clark Trail from Missouri to Oregon in the next two years. The National Council of the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial (www.lewisandclark200.org) is coordinating events, and each state has its own array of festivities. Here are some of the best events and activities to help you reblaze the trail.

Anytime: Take a copy of Lewis and Clark’s journals and a map and go in search of the collapsible canoe they buried, and allegedly never retrieved, somewhere near the city of Great Falls, Montana. Or grab your GPS unit, log on to www.geocaching.com, and treasure-hunt along their trail with the aid of 21st-century technology. At last visit, the Web site listed a cache at Fort Mandan, North Dakota, containing a copy of the journals and Lewis and Clark souvenirs.

June 19–23: Catch first sight of the Pacific from the same perspective Lewis and Clark had on Paddle Columbia: The Lewis and Clark Voyage, a 90-mile trip on Oregon’s Willamette and lower Columbia rivers. River Discovery (503-890-1683, www.riverdiscovery.org), a nonprofit dedicated to hands-on education about river history and ecology, will organize some 100 canoes and kayaks to re-create the last stretch of Lewis and Clark’s journey west. The five-day trip costs $595 per person, including interpretive speakers, history lessons, all meals, and shuttles for your luggage. Rent a canoe or kayak for $125.

June 26–28 and July 4–5: In 1804, Lewis and Clark celebrated their first Independence Day west of the Mississippi with an extra ration of whiskey, a corn dinner, and celebratory gunfire. Kansas City will bump the party up a notch: Festivities planned by the Convention and Visitor’s Bureau of Greater Kansas City (800-264-1563, www.journey4th.org) include an air show, Native American dance, historical reenactments, and fireworks over the Missouri.

June 12–July 30: For hardcore fans who think doing only segments of the trail is for wimps, there’s Timberline Adventures’ (303-368-4418, www.timbertours.com) Lewis and Clark Odyssey, a 3,300-mile bike trip from Wood River, Illinois, to Astoria, Oregon. For 48 days (and $9,000) you’ll be part of a bike posse drafting inn-to-inn behind Airstreams across America.

August–October: Immerse yourself in Sioux cultures and traditions at the Oceti-Sakowin Experience, throughout South Dakota. The nine tribes of the South Dakota Sioux (605-245-2265, www.attatribal.com), descendants of some of the people who saved Lewis’s and Clark’s skins countless times (and on occasion challenged them), will hold historic reenactments, storytelling sessions, musical performances, and an art auction.

September 14–19: Hike the Bitterroot Mountains, on the Idaho-Montana state line, described in September 1805 by a member of the Corps of Discovery as those “most terrible mountains.” Led by Lewis and Clark Trail Adventures (800-366-6246, www.trailadventures.com), you’ll use topo maps and compasses to navigate a path near the old Lolo Trail through pine forests and huckleberry bushes. The Corps was forced to eat candles and melt snow for water. For $1,125, you’ll undoubtedly fare better, but keep some extra candles on hand just in case.