Katharine Green is staging her scene. From her desktop in Las Vegas, she toggles a camera located thousands of miles away, in Katmai National Park in Alaska, panning and zooming before settling on a satisfactory shot. Her sizable live audience of more than 1,000 viewers watches every movement with about a minute’s delay. While Green does everything to keep control of the shot, it’s the actors who are running the show: six rotund, gleaming brown bears.

Green is the head of camera operations at the wildlife-streaming website explore.org. She’s been following a sow and her two cubs with a remotely operated camera as they mosey up the lower Brooks River in Katmai for about 20 minutes (I’m watching via screen share). Soon all three wander behind a bridge. This is as far as Green’s camera can see, but she fires off a Slack message to her co-cinematographer, Kris (who asked to be identified by her first name only). Kris, an explore.org volunteer, is remotely controlling a camera installed on the other side of the bridge. She has been filming another sow with two cubs, who are now about to have a potentially tense encounter with Green’s ambling bear family. Sows are very protective. With bated breath, we watch Kris’s shot, currently tight on her bear group. Kris zooms out as Green’s bears enter and stop just at the left edge of the screen. Green coaches the screen, as if watching a football game: “Move to the left, Kris! Good, good, good.” The bears in Kris’s group stand in surprise; Green’s group backs off. “This is one of my favorite things, when you get to follow them from one cam to the next,” Green says. “That’s when your planning pays off.”

Explore.org is essentially a 24/7 nature documentary, with 170 camera streams set up in eight countries. When you feel like you’re privately screening rambunctious bear antics or snuggling hippos from the comfort of your home, it’s a safe bet that one of the organization’s 80 volunteer camera operators set up that view for you.

While it’s hard to pinpoint a typical volunteer, they all have some common characteristics. These include a voyeuristic passion for animals and an ability to solely focus on their unpredictable ramblings for two hours at a time—and not at work, Green emphasizes. There are volunteers living in Africa and Europe, although many are from the U.S., with 28 states represented. New recruits must be at least 14 years old to sign up, and the oldest volunteer currently on board is 80. Among the ranks are teachers, researchers, accountants, students, bankers, homemakers, a NASA employee, a retired Air Force operations and planning employee, divers, and photographers. Many were fans of the site before they become volunteers; in fact, a lot of them learned about the opportunity on chat boards for their favorite channels. Explore.org wants camera operators to serve as tour guides that viewers will barely notice—an invisible David Attenborough–like hand providing what feels like secret views of animals just doing their thing.

It’s the actors who are running the show: six rotund, gleaming brown bears.

The most complex operation is the brown bears livestream in Katmai, featuring the stars of Fat Bear Week. These bears have the most active fan community, with the stream receiving an estimated 19 million unique visits a year. “There’s not another camera that rivals it in terms of unique monthly visitors,” says Emily Berlin, a public-relations specialist at explore.org. Many of the same bears return every year, and since each animal has a name and distinct personality, the live cams function as a wholesome reality show with a little salmon gore. Filming the brown bears is an art performed in real time with a sizable audience, so explore.org needs its A-team for the task—from late spring to early winter, the organization recruits 35 of its existing volunteers for the Katmai cams, people who can smoothly operate cameras in increasingly complex locations. After all, following penguins in captivity isn’t quite the same as following bears in the wild. “Almost everybody would like to be on the bear cams,” Green says. “But we only put our very best on the bears.”

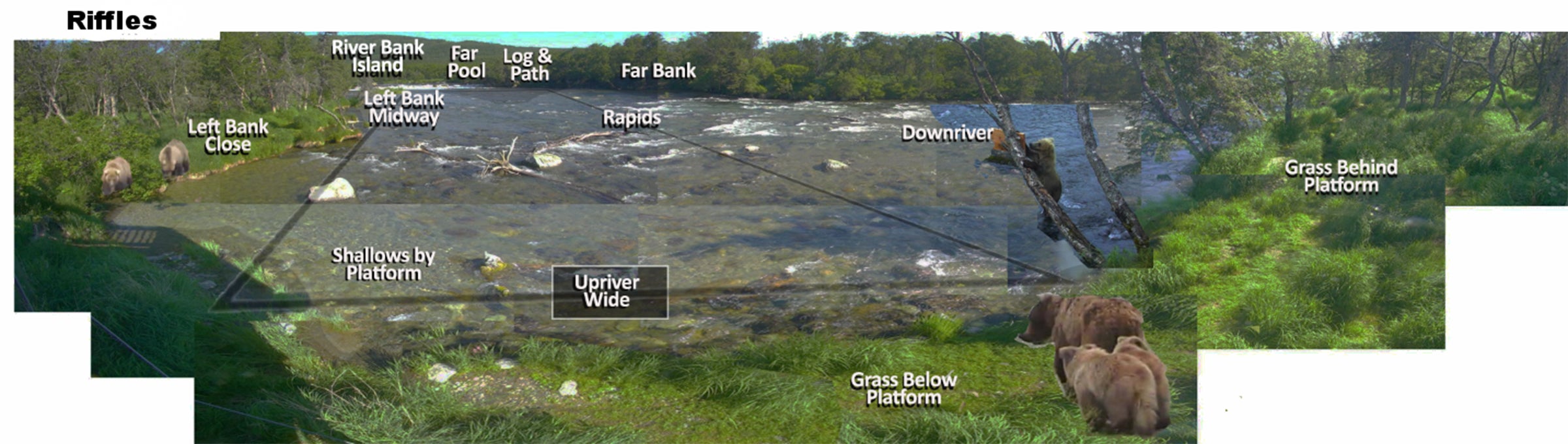

I ask Berlin if I could volunteer for a camera-operator shift for the Katmai livestream, with no training or experience. Naive! “It’d probably be a little better to observe so you’re not in over your head,” she says, kindly adding that it’s a “very coveted position” and sending over a nondisclosure agreement so I wouldn’t reveal any trade secrets. As a 27-year-old who’s been technologically proficient since at least middle school, I think Berlin is just being tactful, in the way a kindergarten teacher would toward an entitled kid at snack time: it just wouldn’t be fair to the others. Then I saw the training guide for its cam ops, with Beautiful Mind–style maps of bear habitats, diagrams of NASA-level desktop setups, and Slack operations I didn’t know were physically possible. So I watched someone else do it.

Even trained volunteers, I later learned, don’t get to run the bear cams right away—they usually need to have operated another camera for at least six months to be considered. But that’s not to say it’s exclusive. “We’re gonna do everything we can,” Green says, to let interested folks be a camera operator. First, candidates must fill out a survey to give a sense of their interests, which nature cams they watch, and their technological capabilities (basically, whether they can work a desktop computer). Everyone who fills out the survey gets the friendliest interview in the world with Green—she wants to put people at ease and get a sense that they’d have fun with it. When she first started volunteering, in 2013, the panda-cam streaming from Happiness Village Baby Panda Park in Sichuan, China, was full, so she was put on the service-dog cam, looking at Great Danes living and training with a Massachusetts nonprofit. Green joined explore.org as a full-time employee in July 2014 and has since operated cameras on every single feed. “You can’t take cam ops away from anybody,” Green says. “Even me. I still have bear shift three times a week. I would not give that up.”

After appointing new volunteers to their stream, Green provides them a guide that she created herself and individually trains them in the fine art of remote directing. She teaches them to turn their desktop screens into mission control for the two-hour shifts: a window for each camera feed on their channel, stacked to the left; a Slack channel where camera operators hand off duties and chat during shifts, in the top left background; a window for each camera they’re controlling (usually one or two at a time), front and center; and a tab open to the live feed on explore.org to make sure their work is showing up in real time and to read comments. Operators often use the cameras like binoculars to search for bear activity by panning and zooming. They rely on their own mental map of the area, knowledge of where bears like to hang out, and eagle eyes to spot tiny ones splashing around in the river. Volunteers can also save preset coordinates that direct the camera to meaningful spots—click on the one labeled “Otis’s Office,” and the camera will immediately swivel to the pool where our favorite champion tends to spend his days fishing.

“We only put our very best on the bears.”

Anna-Marie Gantt, a retired high school marine-biology teacher known as Cam Op Scout, who’s been working the bear cams since 2014 and volunteers at Katmai seasonally, says that when she first started, commenters expected camera operators to answer questions and identify the bears. But now fans seem to know even more than cam ops do, especially when Fat Bear Week rolls around. “It’s hard to ID bears, for me at least,” she says. “There’s a big difference from July to September and October, because the bears have become so much fatter, and they have their winter coat, which is usually darker.” Now separate moderators from explore.org or Katmai jump into comments so cam ops can focus on their job.

That job is far more complicated than a casual viewer would ever guess. Green teaches cam operators to get close-ups without sacrificing resolution, to pan without giving viewers whiplash, and to use preset camera coordinates with care. Most importantly, she teaches them to get out of their own way. The first rule of the bear cams is that it’s all about the bears—cam ops don’t get distracted filming pretty landscapes or other animals like eagles. (Incidental sightings do happen, though. Gantt has caught wolves and moose on camera, but only while following bears.) The best cam ops find the bears and then set up the ideal shot to keep them in frame for as long as possible. “You want it to feel like we’re looking out a window and there are bears there and we’re just watching them,” Green says. “We want the viewer to forget the cam control is there.”

The viewers are grateful, of course; many regular explore.org users will give props to the cam op on duty when they get a good snapshot. (Most operators will introduce themselves when they’re starting a shift—say hi!) But of course, it’s the fun of being a fan that’s kept Green at it for seven years and counting and all her volunteers coming back year after year. Nobody leaves, she says, unless they’re having a baby or have health issues.

“It’s just a wonder, the happiest I am is when I’m on the camera,” Green says about an hour into her shift at Brooks, letting her shot rest on the river. “It’s so relaxing, your blood pressure goes down—” Suddenly, a plump little guy comes into the bottom left corner of the screen, toddling up the riverbank. “Oh! Look, look, look! Got a bear! Glad I’m not looking up in the trees!”