My Quest to Find the Owner of a Mysterious WWII Japanese Sword

(Photo: Paul Kremers)

I. Two Sides of a Single-Edged Blade

Franklin Park, Illinois, December 25, 2021

The sword was suspended in the basement rafters with a message from 1945 still secured to its fittings. My grandfather and I were sitting one floor above it at his kitchen table when an email arrived. It was 9:17 A.M. on Christmas Day in 2021, the Chicago weather too mild, the ground too much of a defeated brown, and the gathering too small to suggest that anything festive was about to happen. A notification lit up my phone with the subject line “Merry Christmas and a letter from Umeki-san.”

The timing was convenient. I was visiting for the holidays, staying at my mother’s childhood home in Franklin Park, ten miles west of Chicago. My parents were there, too. My grandfather, Joseph Kasser, who goes by Ben or Benny, built the home in 1957 for a family of four that eventually dwindled to one. My mom, Kathy, was the first to go, leaving for college in 1971; my grandma Alice died in 2008; my uncle Bob died in 2010. They left Benny alone on Louis Street with a lifetime of modest possessions. Among them was a Japanese sword he’d found on an Okinawa beach in the final days of World War II.

It was six months after I first asked Benny if he’d be interested in finding the sword’s owner. I don’t remember what I said to start the conversation. I do remember that I was nervous asking a man who doesn’t own much to part ways with a keepsake he’d found during perhaps the most consequential time of his life as an antiaircraft gunner in the U.S. Army. He didn’t hesitate. He said, “Sure.”

It was one of those inspired “sure”s that really mean “absolutely,” a posture-correcting “sure,” an energy-intoned “sure,” not “I suppose” or “if you want.” A momentous syllable that set something off. It was apparently something he had considered.

Now, on Christmas Day, I didn’t know if the email that had arrived contained good news about our quest. I read it silently while sitting at the kitchen table, where I had heard one side of the story for more than three decades.

As kids my brothers and I wanted to see the sword, and we wanted to hear Benny’s World War II stories. One of those stories was set aboard a troop ship in the East China Sea at the start of the invasion of Okinawa. A Japanese plane was descending toward the ship as my grandfather and other American soldiers watched from the deck.

“The plane was wounded, smoking and burning,” he told us, panning his hand toward the kitchen table like a plane. “Our Navy guys were shooting at them, and it was coming down like this, wobbling and smoking. Pretty soon the shells started coming down and dropping like hail. If that plane would have landed on the deck, it would have exploded, fire and gas. We would have been all gone.”

Instead it crashed into the sea. Those were sounds, images, and feelings Benny never forgot, and the word kamikaze—referring to a Japanese pilot using his plane, and life, as a weapon—became more familiar to him than any other in the Japanese language.

His training was as an artilleryman, and he’d prepared to ship out to the European theater to shoot 155-millimeter shells in ground combat. But the late-war threat in Japan changed his course, and he headed to the western Pacific as part of an anti-aircraft unit with the Army’s 77th Infantry Division.

He left Hawaii on January 30, 1945, and stopped in the Philippines before a ship carried him to the battle of Okinawa. His ship situated itself in the East China Sea on March 26, among some 1,400 Allied vessels stretching to the horizon, staged for an invasion that would begin six days later.

Shortly after the battle commenced, 21-year-old Benny was ordered from the ship onto a landing craft and carried to the main island of Okinawa. The front of the craft flung open, and he made his way through the shallow water to the uncontested beach, one of the battle’s roughly 182,000 U.S. soldiers.

His antiaircraft duties kept him out of front-line combat, and for the duration of the battle he remained on mainland Okinawa and the nearby island of Iejima. Japanese resistance on Okinawa fell in June, but the war carried on. He stayed there late into the summer as a Japanese surrender started to take shape.

Growing up I was taught a simplified version of World War II history in which Japanese soldiers refused to surrender, even if the alternative was certain death. But in Okinawa, Benny saw Japanese prisoners who had laid down their arms to save their own lives. He knew that if he were in their position, he’d do the same. He saw that as sensible, not weak.

The war ended on September 2 with Japan’s formal surrender. On Okinawa, while awaiting orders for his first postwar transfer, Benny came across a scattering of abandoned weapons near the coast. He stepped over rifles and swords encased in military-issue fittings, all looking vaguely the same. In its scabbard, the sword that caught his eye seemed no more remarkable, but there was something unexpected attached to it. A tag. He picked up the weapon and took it with him when he left Okinawa for Korea on September 15.

Upon arrival in Inchon, he shipped the sword to his parents and hoped he’d soon follow. He didn’t think he’d see it again, but the handlers of the Army post office and the U.S. Postal Service got it from the Korean Peninsula to Illinois in late 1945.

He’d grown tired of answering the same irritating question: Did you kill him?

When Benny came home, he picked up the sword at his parents’ farm and moved with it to an apartment before he built the home I’d come to know. There it occasionally emerged from my grandparents’ basement and into the kitchen, with too many of us gathered around their three-seat table. Benny was modest and quiet while my grandma and elder brother, Erik, nudged him toward the memories. If he complied, Benny began by saying how easy he’d had it compared with front-line infantry.

We were left with an image of him finding the sword. We didn’t consider a next step. When the stories of our grandfather as a younger man were over, the silent blade went back into the cool basement on Louis Street. He didn’t display it. It wasn’t a trophy. Eventually he stopped telling people about it. He’d grown tired of answering the same irritating question: Did you kill him?

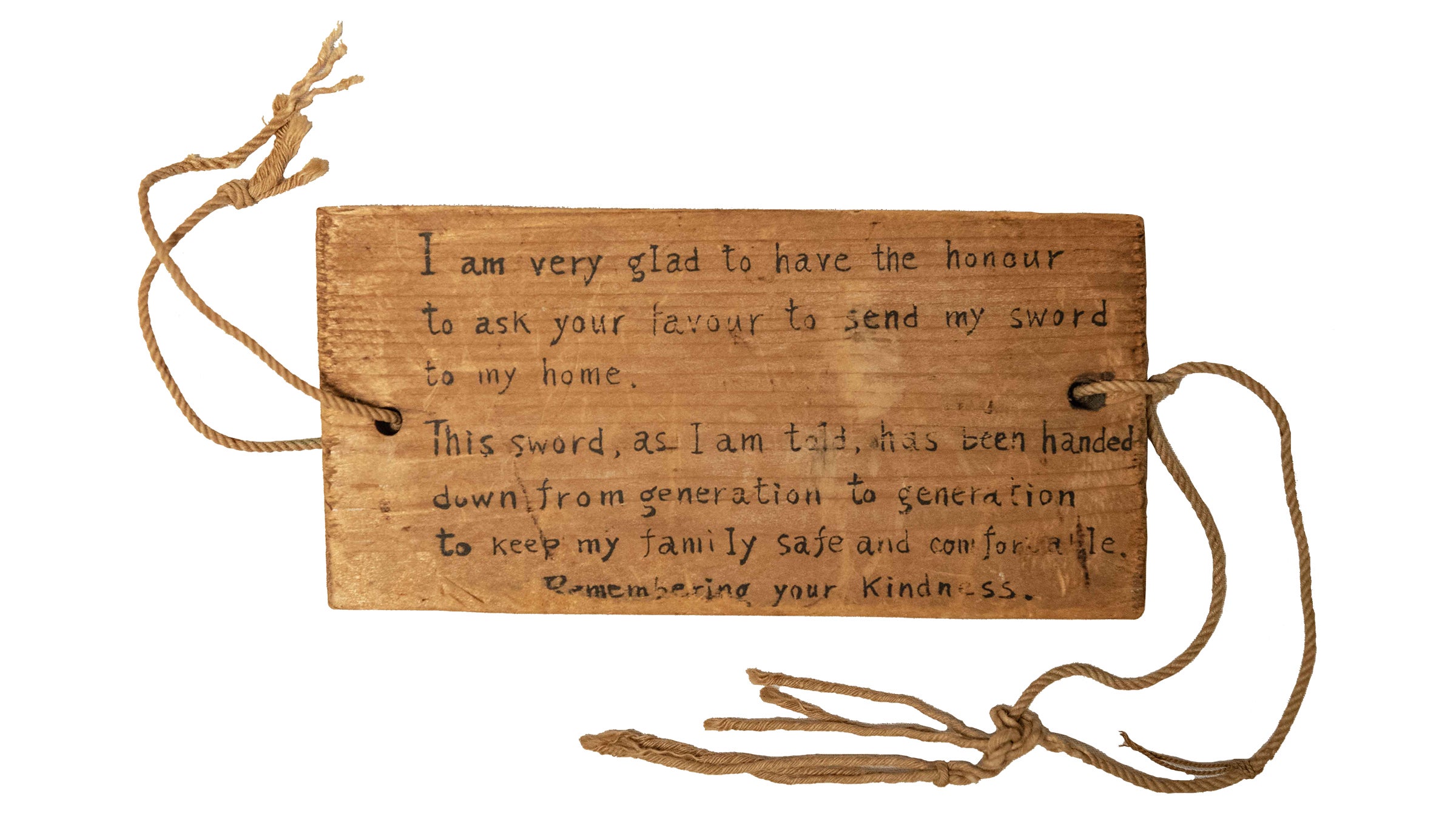

The message attached to the sword was a surrender tag. On one side of the wooden slab, its Japanese owner had inked in perfect British English:

I am very glad to have the honour to ask your favour to send my sword to my home.

This sword, as I am told, has been handed down from generation to generation to keep my family safe and comfortable.

Remembering your kindness.

On the other:

Colonel Tomesuke Umeki

Takaharu-Machi, Nishi-Morokata county, Miyazaki Prefecture.

Takaharu station. Yoshito line.

Takaharu is a town on Kyushu, the southernmost of Japan’s four main islands. West of Takaharu, Mount Takachiho emerges from the green hills of the volcanic Kirishima Kinkowan National Park. The mountain is a significant landmark in Shinto mythology, because Ninigi—the grandson of the sun goddess Amaterasu—is said to have descended there to become the first ruler of Japan, establishing the divinity of all emperors thereafter. Ninigi brought with him three objects: a mirror, a jewel, and a sword—sacred objects that to this day are the imperial regalia of Japan, symbolizing the emperor’s connection to the divine. In Shinto belief, spirits—kami—are not only connected to the shrines constructed in their honor, but also linked to objects, landscapes, and other earthly phenomena. It’s also believed that the deceased can become kami, with certain ancestral heirlooms serving as a tether. Families that own swords may pass them down through generations with such ancestral connections in mind.

Tomesuke had created the surrender tag, petitioning the finder of a centuries-old katana about what to do with it, and sent the sword into the wind—kaze. After forfeiting it, as we were about to learn on Christmas 2021, Tomesuke never spoke of it again.

As I grew up, the sword came out of the basement less often. In October 2019, when my partner, Nichol, and I were visiting Benny, I showed it to her for the first time and noticed the level of detail about the family’s origins included on the tag. The idea of finding its owner became impossible to ignore.

By then the world had become less accessible for Benny. He still lived a self-sufficient life in the home he’d built, but he depended on others to drive him places. He had witnessed the deaths of people he could recall being born. Our relationship had already resembled one of friends much closer in age than of relatives separated by 60 years, and now it deepened. Physical limitations set in, though he remained sharp mentally, and good conversation, generosity, and humor took on greater roles in his life.

Searching for the sword’s owner was something Benny and I could do together. Finding someone on Planet Earth no longer requires going anywhere. So finally we considered a next step.

II. Please Forgive Me if You Are Rude

The Internet and Maumee, Ohio, June 2021–May 2022

Benny didn’t believe that finding the owners of the sword would be possible; I believed it would be straightforward. Neither of us were right.

I envisioned a heavily romanticized version of how things would transpire. The fantasy is showing up at the airport with your 99-year-old grandfather—cane in one hand and unconcealed, carry-on katana in the other—and accompanying him in an adjoining seat, like Uma Thurman and her sword in Kill Bill: Vol. 1. You bring the sword to the small town it came from, going door to door and showing the tag to strangers.

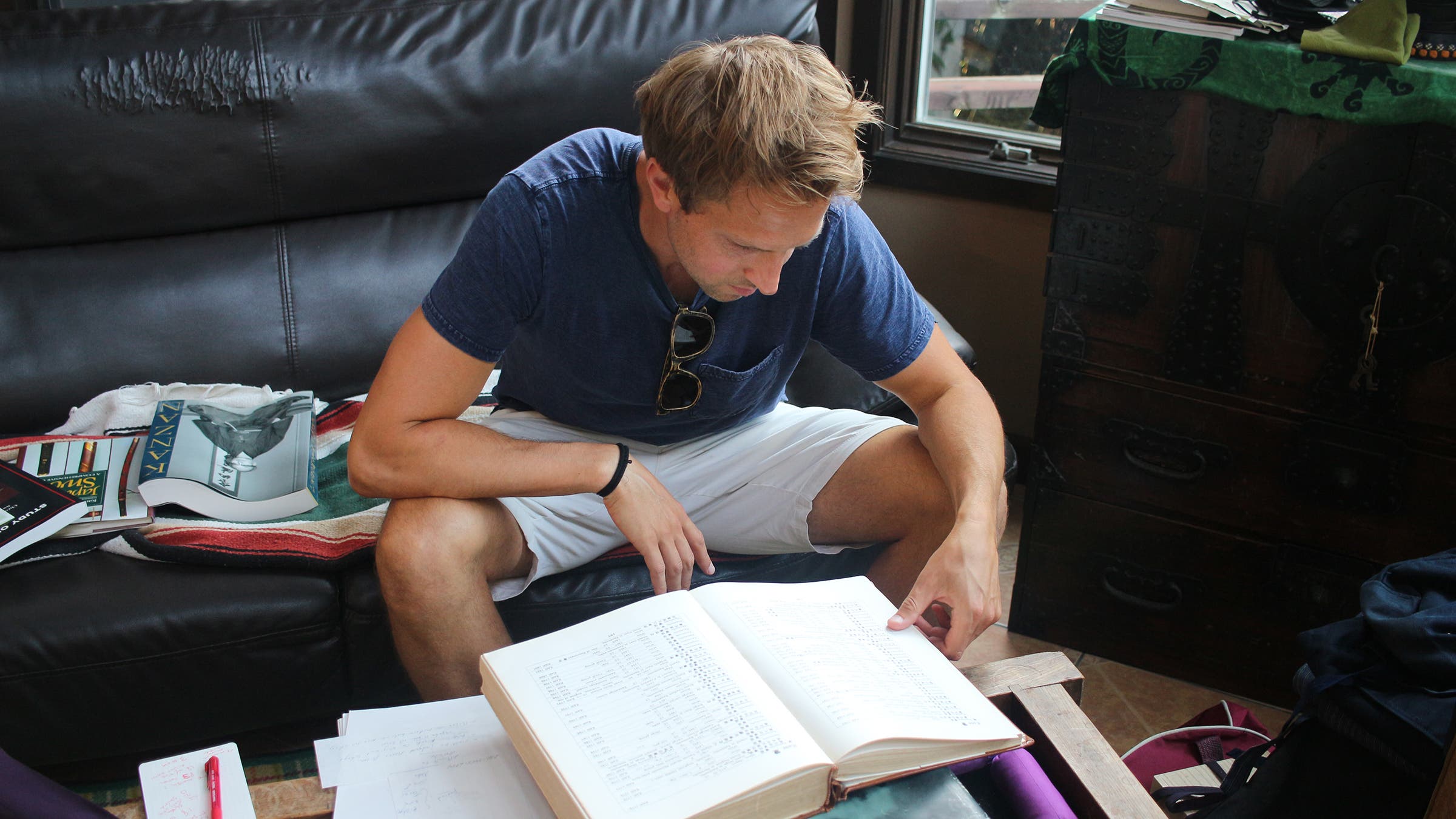

Instead, we typed a name into a search field, which for a computerless 99-year-old is almost as magical. We started with the information on the tag: name and town. Google got us nowhere; the information we sought, if it was on the internet at all, wasn’t searchable in Latin script. Still, we had a name. Takaharu is a small town, population 7,900. People in towns of that size know one another.

Finding someone takes time—and not just your own. The day after I’d asked Benny if he was interested in finding the family, I messaged Yutaka Nakamura, a journalist friend of mine in Tokyo who I met in 2006 while he was covering baseball in San Francisco. It was June 21, 2021. He responded on June 22. He’d already made some phone calls. That’s not just fast; considering the Tokyo–Chicago time difference, it may qualify as time travel.

Yutaka’s messages made it slightly more enjoyable to be stuck in a Chicago apartment during the pandemic. Writing in his second language, he used whimsical phrases like “searching for clues” that lent some buoyancy to what we were doing. In 2021, one settled for internet-based escapades in the hope of realer ones to come.

Via Yutaka, we heard back from a Takaharu town employee that there was no Tomesuke Umeki in the citizen registry. The employee suggested that our next step be consulting something called a koseki—a family registry. But I’d need a lawyer to access it. Hiring a lawyer to maybe or maybe not obtain information on someone who, statistically speaking, was probably dead seemed like a lateral move. Beyond that, I was informed that it was probably the opposite of legal to bring or ship a sword to Japan, owing to the country’s strict weapons laws. So we were a week in with zero answers and two legal issues.

It did seem that there was a slightly more personal way to go about things. Yutaka suggested that I email the town employee in English and further explain the situation. Perhaps the backstory of the search would trigger sentiment and compel a proactive response, “proactive” meaning the cutting of procedural corners. I wrote that email, explaining my intention and asking a stranger for help I wasn’t certain they’d be willing to give, in a language I wasn’t certain they’d understand.

A day went by without a reply. Then a week. Two. Part of me wanted to be persistent, and part of me wanted to leave Japanese people alone regarding war-adjacent matters I had little understanding of.

I thought of plenty of reasons why I didn’t get a reply, from language barriers to uncertainty of how this sort of thing might land culturally. When I forwarded the unsuccessful message to Yutaka, asking for his perspective, an idea occurred to him. He said that before we do anything drastic, before we change course, before we start breaking COVID-19 restrictions and knocking on doors, I should do the following: just send the exact same message to the correct email address.

A reply came two days later, Google Translate’s shortcomings on spectacular display:

Nice to meet you. My name is Yasuhiro Daigaku. I don’t speak English, so I use translation software to write emails. I am not good at writing letters, so please forgive me if you are rude.

The people I worked with in Japan were polite, but this was next-level.

It seemed that there was an Umeki in Takaharu after all, a nephew of Tomesuke. In my mind, that person was perhaps 12 years old, because regardless of the assuredly advanced age of any nephew of a World War II colonel, 12 is the age my imagination conjures for nephews. This nephew apparently didn’t have a phone—good job, parents—so eliciting any information from him would require a visit. Daigaku-san went to the stranger’s home, but nobody came to the door. He left and planned to return, until a fluke encounter at the Takaharu town hall expedited things. On unrelated business, the nephew—92-year-old Kazuaki Umeki—went to the Takaharu offices. When Daigaku realized who he was, he explained the situation with the Umeki sword. Kazuaki told him that Tomesuke had a son named Takemitsu, living in a place called Nichinan. Kazuaki was overwhelmed by the story and gave Daigaku a phone number. We were a phone call away, with the nonagenarian count up to three.

Daigaku made initial contact. It was Mitsuko Umeki, Takemitsu’s wife, who answered the phone. The call was from a man in a town from her family’s past, informing her that someone in the United States had something that belonged to her father-in-law, who’d died in 1974. Her husband wasn’t home. She asked for a letter to be sent, and after hanging up she thought it over, wondering whether things like this really happened, and experienced the peculiar sensation that comes from finding out that someone you don’t know has been searching for you. News spread through the family while they waited for the letter.

Seventy-six years after Tomesuke wrote the note on the tag, Benny and I responded. Yutaka translated, and we mailed our letter from the U.S., in both English and Japanese, with photos of the sword and the tag. A line in the letter that came directly from my grandfather: “He probably wasn’t so different from me, only born on the other side of the world.”

In Japan, the saying riku no koto is used to describe a place that’s so close yet so far away, inaccessible despite its proximity. The literal meaning is “out-of-the-way place” or “remote land.” In Miyazaki prefecture it pertains to the hilly, densely vegetative landscape of the region, the need to travel much farther than a straight line from A to B. Google Translate occasionally spits it out as “island of land.” Which is at once redundant and profound.

We waited for the letter to be carried around the world, and for the second time in this story, a chain of postal services delivered.

I put my phone down on the kitchen table and told Benny about the email. Yutaka had received a hard copy of a letter from the Umeki family and translated it. I read it to Benny.

Tomesuke Umeki had written the first message in 1945; we had written the second nearly 80 years later; and Tomesuke’s son, Takemitsu Umeki, had replied with the third. His message began like Tomesuke’s had ended: “I’ve read a letter from you and appreciate your kindness.” He explained that Tomesuke, a colonel in the war, had died in 1974 at the age of 74. Takemitsu, who was 96 years old when he wrote to us, said he remembered the sword from before the war. His father had left home with it but returned unarmed.

“My father did not talk about the sword when he came back from the war,” Takemitsu wrote, “so I believed that the sword was forfeited to the U.S. Army.”

Takemitsu was surprised to see the state of the gently curving blade in the photos we’d sent, the gleaming steel effectively free of rust to a novice inspector, the rolling temper line along the single-edged blade still apparent, perhaps not so different from how it looked to him as a teenager when it went to war on his father’s hip.

Takemitsu also served in World War II, and was 20 when it ended. He had two swords, one given to him by his father. Japan was demilitarized as a condition of its surrender; all swords, even those not used as war weapons, were required to be forfeited to the Allied forces that occupied Japan until 1952. Rather than handing over his after the war, Takemitsu brought them back to Takaharu and buried them. When he unearthed the swords two or three years later, they were completely rusted. He threw them away.

The letter described his father returning in November 1945 from Jeju, Korea. This didn’t fit neatly into the narrative we’d pieced together since starting the search. We’d assumed that Tomesuke had ended the war on Okinawa, where Benny found the sword.

Finding a person no longer requires going anywhere, but properly returning what’s theirs might.

Upon returning to his family in Takaharu, the colonel—initially prohibited, along with his son, from holding public office because of his position as an officer in the Imperial Japanese Army—was resigned to a simple, peaceful life farming the rich land of Miyazaki prefecture. (Many former military officers and their families were prohibited from holding political office under the U.S. occupation of Japan, immediately following the war.) The Umekis spent the early years of their post-military lives working as father and son. Eventually, Takemitsu started his own family and moved to the coastal town of Nichinan. The letter ended with gratitude and acceptance of the proposed idea of the sword making its way home.

My grandfather was finally hearing the other side. I asked him what he thought. He paused, then went back 76 years.

“I’m not the smartest guy, but when I saw the tag, I knew it meant something. There was a story there.”

It was a touching moment with a level of clarity—before things again got complicated. The Omicron coronavirus variant was just getting started, and travel to Japan was prohibited. Finding a person no longer requires going anywhere, but properly returning what’s theirs might. We also learned that there weren’t just two sides to the story. There was a third—the sword’s—and none of us, Takemitsu included, knew anything more about it.

When you first think about attempting something like this, your fantasy is simple. The imagination can’t be bothered with unromantic minutiae. With weapons laws. Consulates. Viruses. Visas. Visa sponsorships. Complications of traveling with 99-year-olds. The companionless void of traveling without 99-year-olds. Shipping restrictions. The impossibility of finding a cardboard box suitable for shipping an object similar in size to the bones of a fully extended human leg. Sword licensing. Extremely limited dates on which it’s possible to license a sword.

I began addressing the logistics of getting the sword and myself into Japan. For me it was a COVID waiting game. For the sword, I lacked confidence in the two options available: flying with it, and sending it ahead to Tokyo. Did I want to show up at American and Japanese airports with a three-foot sword? Yes, kind of. Being escorted into back rooms for questioning by TSA officials had a curious appeal after so much of the initial work had been carried out on a screen. But the more people I spoke with who’d transported swords internationally, the more it became apparent that we would both benefit from traveling alone. Assuming that the sword would be allowed back into Japan as an antique art object, it had a frictionless path into the country: the mail. It felt fitting for the sword to make its journey back home on its own, just as it had left.

In November 2021, Japan announced that it would resume admitting business travelers from certain countries. Securing an official assignment for this story checked the business box for my entry to Japan. But I still wasn’t willing to ship the sword to Japan without first learning more about its history, on the off chance it got stuck in licensing limbo or confiscated. I wanted a sword expert to judge it in person before it left.

After emailing with the Umekis, I came to understand how the blade’s changing of hands in 1945 together with Tomesuke’s death had effectively erased its generational story. Simply giving it back didn’t strike me as sufficient. It seemed that we’d be giving back less than we’d taken. Our family had contributed to the erasure, so it followed that we should do what we could to restore what was lost.

Just as I learned about swords going into Japan, I also began learning about the global subculture born from Japanese swords leaving their homeland after World War II. That subculture had an informed voice in Maumee, Ohio.

Mark Jones is a collector and dealer who runs some of the leading U.S. sword shows. He was the first person to remove the Umeki blade from its fittings in at least 77 years. It happened very publicly and without ceremony at the Maumee Antique Mall hot dog café, where encased meats can be consumed while encased blades are examined.

Jones had inherited a sword his grandfather brought home from World War II, a common means of entry to the U.S. sword community. He wanted a better one. He bought a better one. A cycle of buying and selling swords as a means of buying and selling more swords followed. He’s trafficked in thousands of blades, and has about a dozen in his possession at any time. He kept the one his grandfather returned with, but he’d also let that one go for the right price. That might sound cold, but this is how collectors maintain their hobby. Their love for what they do is greater than that for any one object.

My questions for Jones were: 1) Who made the sword? 2) When? 3) Where? 4) Can I send it to Japan?

Japan’s strict policies about personal weaponry stem from being demilitarized by Allied forces immediately after World War II. Those laws have evolved. At the national level, due to regional tensions, this meant the 1954 formation of the Japan Self-Defense Forces, which included ground, air, and maritime forces. On an individual level, it meant the implementation of the first sword registration system, in June 1946, with limited sword production legalized in 1953. The key distinction for legality was and remains artistic significance. To be licensed without complications, swords entering Japan need to qualify as antique pieces of art by having been handmade at least 100 years ago. More modern blades can be licensed as well if they qualify as art objects.

Any reasonably trained eye will know quickly whether a blade qualifies, and Jones said that Tomesuke’s did. Evaluating whether it was handmade started with the temper line—the hamon in Japanese—which is the outline running along the blade’s cutting edge. Japanese swords have a single cutting edge, like a kitchen knife. That said, it’s unlikely you’ll find a temper line on a department-store knife, because those are manufactured and not hand-forged using traditional methods.

Jones explained that a unique aspect of Japanese swords is their variable strength in different parts of the blade. This is achieved through a process called differential hardening, which ensures that the metal is harder along the cutting edge and more flexible along the spine. Near the end of the sword-making process, the smith applies clay to the length of steel they’ve been heating, folding, and pounding. Clay insulates the steel from heat—less insulation results in harder steel, so the smith applies less clay to what will become the cutting edge. They heat the blade to the desired temperature and then plunge it into water.

The blade can be submerged in oil instead, but this is more common with mass-produced, machine-made blades, Jones said. In water, temperature transfer is quick and violent, causing more crystallization to form on the surface of the steel. This is rougher on the steel and sometimes causes it to fracture. In oil, heat diffuses more slowly, resulting in a moderate hardness, and the process is less likely to damage the sword. For those whose interest in swords is artistic, the reward for risking damage is a harder, more visually appealing blade.

The sword is then polished and the complexities of the temper line, a result of the clay application, are exposed. Each handmade blade has a unique temper line. Some are straight and stay consistent with the edge of the blade. Some are noticeably irregular. “If it was oil tempered, it would be more uniform—the line wouldn’t have as much individual feature,” said Jones, angling the blade in the light. “Whereas this one is clear and bright.”

You can look at a blade and consider what you see. You also have to consider what you don’t see.

Answering the question of who made the sword required removing the handle to expose the tang, the steel extension of the blade underneath. Bamboo pegs held the handle in place. Jones tapped them out and the handle popped off smoothly. After forging a sword, a smith inscribes their signature along the tang. Except this tang was mumei—nameless.

“It could be that it was signed, but it’s not anymore,” Jones said.

How does a tang lose a signature? Because it has undergone suriage—shortening. It’s not uncommon for swords to be shortened to meet the functional needs of the day.

Signature or not, Jones confirmed that, yes, the blade was more than 100 years old and qualified as an antique. Its age wasn’t surprising, given that my grandfather had possessed the sword for nearly 80 years. What was surprising was that Jones estimated the blade to be at least four centuries old. The primary way for him to assess this was through its shape, the key characteristic that differentiates sword-making eras. Had it been made more recently, it likely wouldn’t have had as much curvature. In the late 1500s and early 1600s, katanas became less curved. He speculated that the sword’s origins could be traced to either Bizen province (roughly modern-day Okayama prefecture, between Kobe and Hiroshima) or Mino province (roughly modern-day Gifu prefecture, north of Nagoya), then said that there were more qualified people to weigh in on specific geography, sword school, and smith. I’d be visiting such people in Japan. Before we left, Jones told me that he’d share his evaluation with them.

Back in Illinois the next day, for the second time in his life, Ben Kasser approached a postal employee with an informally packaged sword and sent it around the world. Thus ended his eight-decade custodianship of the blade.

The idea, fanciful or otherwise, had been for my grandfather and me to go to Japan together, but this would be the end of the line for him. He had decided over the winter that he wouldn’t be able to do it. I told him that I’d see him on Zoom from Nichinan.

There was still plenty to resolve before then. Jones had unearthed our most daunting question yet. To find the Umeki family, we’d had a name and a town. Regarding the origins of the sword, we had neither.

But there is a man outside Tokyo who does his best to bring those details back to life.

III. My Sword Guy’s Sword Guy’s Sword Guy

Tokyo and Tokorozawa, Japan, June 25–26, 2022

You deconstruct a sword to reconstruct its story. Each time you take it apart, ideally you get a little closer.

On my first full day in Tokyo, I took the subway to the Ginza neighborhood to pick up the sword at Seikodo, the sword shop to which we’d sent it to handle licensing. With Japan still closed to most foreign visitors, I was an oddity on the streets of a typically global city.

At Seikodo, I met the shop’s fourth-generation owner, Hisashi Saito, and Robert Hughes, a Kamakura-based sword expert and, at the time, a professor at Toyo University. I connected with Hughes through Jones and corresponded with him before my trip. Hughes had been a part of the sword community in Japan for four decades, after making what turned out to be a permanent move from Saskatchewan and starting Keichodo Fine Samurai Art to assist in repatriating and restoring blades. His generosity and connections in the sword world seemed limitless.

Saito presented me with the blade’s newly obtained license, issued by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. It was gratifying to have been in Japan for slightly more than 24 hours and already, at least temporarily, be the carrier of a licensed blade. I also felt like an impostor.

My friend Yutaka met us there, and—surrounded by glass-encased blades and suits of samurai armor—we looked, listened, and posed entry-level questions to the sword experts.

Saito tapped out the pegs. He and Hughes quickly placed the blade in the same era Jones had, and speculated on three geographical origins, two of which were mentioned by Jones six weeks before.

Based on the blade’s size and curvature, they agreed without hesitation that it was a mid- or late-Muromachi-period blade, meaning that it was likely made in the 1500s.

“It’s a significant blade,” Hughes said. “When this is restored, it would be a fine piece to hold in a collection.”

If polished properly and preserved in a wooden storage scabbard called a shirasaya, with the occasional application of a lubricant for preserving blades from rust called choji oil, a sword like this will outlast all of us and the grandchildren of our grandchildren. There are Japanese swords that have endured since the Heian period (794–1185) without serious damage. As Hughes observed, it’s a significant blade, but there’s a difference between significant and exceptional. The Nihon Bijutsu Token Hozon Kyokai (NBTHK), or Society for the Preservation of Japanese Art Swords, judges quality through a process called shinsa. If a blade is submitted to the NBTHK and the society recognizes it as significant, it’s then classified according to a hierarchy with four tiers. This differs from licensing. Receiving a sword license in Japan, as I just had, is a matter of law. “Papering” a sword through official shinsa is a choice.

Above the four tiers used by the NBTHK are blades that are of extraordinary importance to Japan. For those, the federal government gets involved and determines whether to designate a blade bunkazai kokuho, meaning that it’s considered a national treasure and must remain in the country. Japanese smiths have made an unfathomable number of swords and fittings. Among them fewer than 150 have been designated kokuho.

Many swords aren’t paperable at all, according to Hughes—they aren’t significant enough to merit the base-level Hozon certificate. We chose not to submit the Umeki sword for shinsa, because it wasn’t relevant to the act of returning a family treasure. But Saito and Hughes—who are NBTHK members, though they don’t perform official shinsas—agreed to take an informal stab at categorizing the sword. The evaluation we were doing at Seikodo was purely informative. Nevertheless the sword, according to Hughes, was paperable. Barring something unforeseen that boosted it higher, he presumed that it would be given a Hozon certificate.

A blade must be maintained to keep it paperable. This is the responsibility of its current holder, or custodian. If this 500-year-old blade was transferred every 50 years to a new custodian, that would make ten of them. Each had a responsibility to ensure that it didn’t rust and wasn’t damaged. A break in that lineage could mean the end of the sword in optimum condition. It’s a heavy unwritten agreement, one my grandfather certainly wasn’t aware of, but the blade had aged well in his care. It could now be professionally polished and properly maintained.

Five centuries ago, someone somewhere on the Japanese mainland constructed this sword. But where? And who?

Saito and Hughes had given us what they could. We finalized our plans to visit the man they learned from.

Michihiro Tanobe tidies his study for no one. It’s actually a small apartment dedicated to his things, while he and his wife live in comparative order next door. The space is overrun by documents and books; blades and sword fittings; the occasional shirt on a hanger that’s not hanging on anything; model planes; and a Glenn Miller CD. It’s a befitting manifestation of a mind full of wide-ranging connections.

Hughes and I took the train, both of us with blades in hand, an hour and a half northwest of Tokyo to Tokorozawa to see Hughes’s sword guy. And Hughes’s sword guy is the sword guy of all sword guys.

Tanobe-sensei studied under Junji Homma and Kanichi Sato, the sword experts who’d established the NBTHK. The duo had begun working to preserve swords in the years following the war, approaching postwar occupation leaders when blades were being piled onto barges and dumped in Tokyo Bay or tossed into furnaces as scrap metal. It was a delicate time to request the liberation of weaponry in Japan, but they hoped to spread awareness of Japanese swords as art objects with significant national and familial meaning. Tanobe estimates that their preservation efforts saved more than three million swords from disposal.

Tanobe retired from the NBTHK in 2010, but he remains active in the sword community as an author, journalist, teacher, and calligrapher. At Hughes’s request, he agreed to inspect the Umeki sword.

Tanobe told us his story, mostly in English, between focused evaluations of the sword. The first few times you see someone do this, really inspect a sword, it can come across as a show—a drama even, depending on the person. Tanobe’s style is engaging but stops short of theatrical. It’s practical and unemotional; he’s a doctor who has performed surgery a thousand times.

Tanobe looked at the blade’s tip—the kissaki—then shifted his attention to the temper line. A smith can make any number of creative choices when applying the clay before heating and quenching. Intricate patterns may be imparted that will then transfer to the steel. These can be obscure, or they can be representations of the natural world such as falling leaves, blossoms, or a small-scale Mount Fuji. The results of those artistic choices aren’t apparent until the blade is heated, quenched, and then handed off to a polisher to complete the shape and finish.

“Difficult blade,” Tanobe said. The attribution process was not going to be straightforward. He tilted his head and angled the sword in the light. Occasionally he drifted into Japanese, and Hughes translated.

Focusing on the properties of the steel, someone assessing a blade will note the appearance of its martensite crystallization, which is what Jones in Ohio was looking at when he determined that the blade had been water tempered. Due to the violent transfer of heat as the steel is quenched, there are near microscopic features of the metal’s structure that appear visually distinct.

Tanobe brought out a loupe. He was inspecting the pattern left during rapid cooling, a seconds-long event that had taken place back when Hernán Cortés was still alive.

Tanobe differentiated between nie, nioi, and other features of the steel. Nie is a more distinct crystalline feature—identifiable stars or bubbles, for example. Nioi is faint, like a haze of stars or a mist. Both of them can indicate region, school, and smith. “Nie is stronger than Bizen,” Tanobe said, eliminating one of the regions under consideration.

It was starting to come together.

Closeness can be achieved despite language barriers. You find a way to understand.

During my time in Japan, Hughes explained roughly eight centuries of craftsmanship from which a sword’s lineage may be traced. While some of the details may be contested, the history he told me is generally accepted by the NBTHK and the wider sword community as a useful foundation for their work. In the Kamakura period (1192–1333), Japan’s ruling powers brought the country’s finest swordsmiths together in the ancient capital of Kamakura to drive the craft forward. From that meeting grew one of the five main sword schools in Japanese history. It was called the Soshu Den. Its evolving work aimed to meet the need for Japan to defend itself against the recurrent threat of invasion. Goro Nyudo Masamune emerged as the leading smith. Masamune is believed to have taught ten main pupils the techniques of the Soshu Den. It became the golden age of sword making.

Those pupils struck out on their own, Hughes explained, and the craft spread to other geographies, evolving in each. Of the ten, Shizu Saburo Kaneuji’s style is most often linked to his master, to the point that some of his swords were mistakenly identified as Masamune’s. In central Japan, Kaneuji’s work took hold in what was then Mino province.

Fast-forward to the early 1500s, and the kind of work being done in Mino province changed, specifically in the town of Seki, 30 miles north of present-day Nagoya. Hughes said that up until that time, many smiths imparted temper lines according to what was essentially a regulated standard—think of a line running parallel to the cutting edge. Nothing too flashy. Then they began branching out, doing work that felt less restricted—think of a temper line that resembled rolling waves, a rounded EKG line, rising flames, or a forest. The Umeki sword had fiery-looking peaks running across its temper line.

Tanobe put the sword back in its scabbard and opened a black leather-bound book called the Nihonto Meikan. It detailed over 20,000 swordsmiths from recorded Japanese history.

“Interesting blade,” he said, making notes on a pad. He removed the sword again, presumably to check it against information from the book. Then he handed me his written attribution.

He believed that the blade, with its temper line, curvature, tip, and crystallization, was made in the Seki area during the first part of the 1500s. As the work of Kaneuji’s disciples changed, some previously common features disappeared. Sunagashi was one of those features, Hughes said. The term refers to patterns that look like the remnants of swept sand. And sunagashi was one of the details the Umeki sword lacked—otherwise, Tanobe might have dated the sword to the 1300s. You can look at a blade and consider what you see. You also have to consider what you don’t see.

Tanobe’s attribution is to two smiths, a father-son duo named Kanenobu and Nobutsugu, working in Seki in the Eisho era (1504–21) and the Daiei era (1521–28). The attribution isn’t a certainty, but instead a very educated guess, as is the case for many swords.

The sword Benny found is far from a national treasure. But it is still a distinguishable level of work from a very different time.

“Good blade,” Tanobe relayed. “Difficult blade to attribute, but good blade.”

Good enough to give back.

IV. Proximity

Nichinan, Miyazaki Prefecture, Japan, July 2, 2022

The crowd had gathered before my arrival on the second floor of the Umekis’ Nichinan home. The focal point of the room was a wooden sword display crafted by 97-year-old Takemitsu Umeki in the weeks before my arrival, the two upright supports awaiting the return of his father’s blade. It sat beside a shrine and flowers. Behind the stand was a framed black-and-white photograph of a Japanese soldier with his hand on the grip of a sheathed katana.

Chairs around the perimeter of the room were occupied, except for one next to me, reserved for my family’s tiny faces on a laptop screen. National and local media were interested in the story, so television cameras and journalists stood behind those seated. The room of perhaps 25 people had serenely greeted me as I walked in with the wrapped sword. My parents were with Benny at the Franklin Park kitchen table.

Like Takaharu, where Tomesuke lived, Nichinan is on the island of Kyushu. There, in the 13th century, the Mongols twice attempted invasion under Kublai Khan, the grandson of Genghis. Typhoons hit and disrupted Khan’s plans. The word kamikaze entered the Japanese language to describe the force that had deterred the conflict. For most of the 700 years the term has existed, the meaning of kamikaze had nothing to do with suicide missions. Kamikaze means “divine wind.”

The utility of a sword also evolves. The Mongols were well armored, so the structure of the Japanese sword changed, and Soshu smiths pursued a heavier, longer design capable of piercing armor, according to Japanese lore. Perhaps 250 years later (based on Tanobe’s estimate), the Umeki sword at its original length had been based on that style.

Ahead of the meeting, I had outlined the parts of the sword’s story I would share. Takemitsu and Mitsuko’s granddaughter, Masae, translated. It may not have been the story Tomesuke would have passed down to them, but it was the best I could offer. I couldn’t tell the family how it had come to possess the sword generations prior, but at least I could give them a place to start.

Seated, I picked up the sword and untied the orange tassels on the decorative bag given to me by Hisashi Saito back at Seikodo, made of a soft olive brown cloth with an orange and white floral pattern. I removed the sword and placed it on my lap. Then I held it horizontally and stood to meet Takemitsu Umeki, who stood with me. I bowed, offering the sword, and in Japanese said, “Umeki-sama, anata no nihonto. Watashi no sofu kara.” The phrasing had been cleared with Yutaka, and I’d practiced it repeatedly in front of a mirror at three different hotels, my bow never as straight as I wanted. It was the simplest way I could find to express in Japanese what I was doing: “Mr. Umeki, your Japanese sword. From my grandfather.”

We held the sword together for a moment, and then I released it as my grandfather watched. Here was a 99-year-old man returning to a 97-year-old man his father’s sword after 77 years. Then it was placed atop the display by Takemitsu’s son, Toshihiro, the blade finally home, two generations later without missing one.

The media left, and I got to speak more informally with the Umekis. I met Kazuaki Umeki, the nephew of Tomesuke from Takaharu, who had given Takemitsu’s phone number to Daigaku, the Takaharu town employee. After my grandfather and I had sent the letter to the Umekis, it made its way to Kazuaki in Takaharu. Through tears, he read the letter aloud to a photograph of Tomesuke, hoping that his uncle would hear our words. Daigaku had also made the trip to Nichinan to witness the return—another extraordinary act from a stranger. I was able to thank him and tell him that none of this would have happened without him.

When we couldn’t express something properly because of the language barrier, we put our hands on our hearts and looked at the person we were speaking with. We’d say something like “warmth.” Closeness can be achieved despite language barriers. You find a way to understand.

Takemitsu’s daughter, Yoriko Shiwa, recalled her deceased grandfather Tomesuke, memories she hadn’t had in decades. Takemitsu’s daughter-in-law, Yukie Umeki, said that she felt closer to a man she’d never met. They put their hands over their hearts and said that they felt him.

“The spirit of the past is being passed on,” Takemitsu said through an interpreter, and then spoke briefly of the importance of what we were doing in a traditional Japanese sense, and how that had changed more recently in Japanese culture. “The ideologies that come with the katana are so ingrained with what we are that I find it to be very important. But the way people are educated now is very different than in the old days. So I don’t know if it translates to a new generation, but I like the fact that the spirit of the past is being honored right now.”

What Takemitsu said stirred up complex feelings for me, given the history I’d been studying throughout this process. I hadn’t questioned the importance of the katana in Japanese culture. Rather, I had considered World War II’s larger history. In the years leading up to U.S. involvement in the Pacific, the Imperial Japanese Army did deplorable things in China that amounted to mass murder, as well as rape, torture, medical experimentation, and forced labor. Some Japanese officers and soldiers were tried by an Allied military tribunal and sentenced to death for their war crimes, but many more were never prosecuted.

In our communication before I went to Japan, the Umekis were forthright about the fact that Tomesuke had spent most of the war in China. I considered this before finalizing plans to return a sword that still wore its military fittings.

I asked the Umekis if Tomesuke had ever been implicated or charged in any of the atrocities, and they said that he had not. Tomesuke’s military records, which I had translated, make no mention of war crimes and do not place him in Nanjing, where the Japanese military massacred more than 300,000 Chinese civilians in 1937. Those records also indicated that Tomesuke had not been made a colonel until nearly the end of the war. He was promoted in 1945 in Korea. But he was a battalion commander in May 1938, and was in combat in China on and off from 1937 to 1943.

When we can’t explain something logically, when there are gaps, we jump to divinity.

In deciding to return the sword, I focused on this: Maintaining possession would have kept it in my family as a Japanese military weapon and nothing more. Doing so felt like an act of perpetuating division and silence, however small the scale. Returning the sword took it out of its military fittings and revealed a history far greater than several years at war. It brought two families together, with acts of kindness on both sides.

That day in their home, the Umekis were the ones to bring up the ugly nature of those times in their country.

“In elementary school, we were taught that we needed to go with the country,” Mitsuko said via the translator. Mitsuko, 88 years old, was among the generation who saw nationalism change from being the dutiful way of life in Japan to something that should be questioned. “In contrast to now, where it’s a democratic society and we honor the individual. It’s so different, because it used to be about there being one single goal you had for your country to prevail. It’s not just about focusing on your own country anymore. It’s much more than that. It’s about learning to live together peacefully.”

The spirit of the past was being honored and questioned at the same time, but the story of the past was still incomplete. I asked Takemitsu whether his father had been on Okinawa during the war. He confidently said that he hadn’t. Military records confirm this. I asked if his father had been a prisoner of war. Again he said no.

We don’t know how the sword got to Okinawa. My grandfather is as certain as the passage of 77 years allows that he acquired it on Okinawa and that it accompanied him in his duffel bag on a landing craft all the way to Inchon. Because he would have passed the Korean island of Jeju from Okinawa to Inchon, this gives me some pause. We know from Tomesuke’s military records that he was in Jeju at this time. Could my grandfather have stopped there and picked up the sword after the Japanese surrender? It’s possible, but he remembers having it with him when he left for Korea.

Benny’s military records were lost in a 1973 fire at the National Personnel Records Center in Saint Louis. His memory and notes are what we have to go on. His notes mention every place he went from Seattle to Inchon, and they make no mention of Jeju.

There was time after the Japanese surrender and before Benny’s departure from the country for the sword to make its way south across the sea from Korea, perhaps as part of a weapons dump, but that’s speculation. When we can’t explain something logically, when there are gaps, we jump to divinity—perhaps divine winds. Riku no koto. So close yet so far. Inaccessible despite proximity.

It felt like the right time to stop prodding the past. It seemed like I may have been the only person who cared about those details.

Part of the story of the Umeki sword may have been lost, but the sense of unfinished business dissipated. The mayor of Nichinan came by to express his gratitude and suggested displaying the sword in the town. That night we had the uncomfortable experience of seeing ourselves on the news. The next day, newspapers reported the return of the blade in Japanese and English. People from the sword community reached out. Portions of the story were gone, but a new chapter was being written.

V. Grandfather

Iejima, Okinawa Prefecture, Japan, July 2, 1945, and July 5, 2022

For as long as my grandfather has spoken to me about war, he has valued the individual caught in the conflict. He’s now a 101-year-old man living on his own, sometimes desperately doing all he can to maintain that independence. He’s still of the belief that the average Japanese soldier wanted to be fighting no more than he did. I think the message on the sword’s tag, with its reminder of the name and generations of another family, helped him believe this whether he knew it or not. Tomesuke wrote it with a voice that expressed humanity during a time when it was difficult to do so, asking an enemy for assistance. The sword was very much a weapon to Benny then, but over time it became anything but.

“When I saw the tag, I knew it meant something.” He’d said some variation of this line to me more than any other while going through this process. It was clear that he wasn’t referring to the literal meaning of the tag.

The sword won’t be passed down through generations in my family, as we once thought it would be, but Benny’s mindset of being able to consider the humanity he shared with a single person in an overwhelming conflict already has been.

I spent the days following the sword’s return on Okinawa. I went by ferry to Iejima. As a part of Japan, off the Okinawan coast, Iejima is an island’s island’s island. On it remains the main geographical marker in all of the western Pacific that allows me to identify where my grandfather was with any level of specificity. It’s in a photograph. On April 18, 1945, American journalist Ernie Pyle was killed on Iejima. Before his death, he wrote stories about ordinary soldiers. A temporary monument to Pyle was constructed the day of his death, and a permanent one was unveiled in a dedication on July 2, 1945. At some point that summer of 1945, quite likely on the day of the dedication, my grandfather had a photograph taken of himself crouching next to it.

The monument is still maintained, located atop a mound on a plot of grass surrounded by farmland. On July 5, 2022, I walked out to it from the island’s port in the wet heat. It was quiet, with a pre-storm stillness.

There wasn’t anyone around to snap a photo, so I checked the pose in the photograph of the photograph on my phone, then propped the device on a step with the timer set, ran to the monument, situated my feet where he’d been standing 77 years before, crouched, and posed as best I could as a young Ben Kasser.

It started raining, then pouring. I hung my bag in a tree and sat beneath it. I looked over at the white monument my grandfather and I had both crouched next to, our feet as close as they could have been despite being as far apart as they’d ever been.

I thought about one person carrying on in another. Dependent immortality. Less so in the Shinto way, because it’s not my grandfather’s sword to live on in. It’s easier for me to grasp living on in a gesture, an act. Benny’s life will be remembered as a series of small acts of entertainment and large acts of kindness. Returning the Umeki sword may be the last and greatest of those acts.

Eventually, a taxi pulled up. A middle-aged man emerged, striding enthusiastically, unfazed by the rain, while the driver waited. He took a series of photographs of the monument. I went to the taxi to ask about a ride. The man returned, wordlessly understood my situation, and gestured for me to share the car. One of us said, “Ernie Pyle,” as if to express interest or inquire to the other about being the only other person out here in the rain on an island’s island’s island. I showed him the photo of me posing. He nodded politely. I showed him the one of Benny posing and recalled the word sofu—grandfather—from my pronouncement to Takemitsu. He lit up, gesturing with his phone to ask permission to take a photograph of a photograph of a photograph.

Back in Maumee, Ohio, Mark Jones, after inspecting the sword and before sliding it back into its scabbard, had picked up a microfiber cloth and carefully wiped the blade. He explained that this was important because any handling could leave permanent fingerprints. I didn’t think anything of it at the time, aside from how it was meant—a helpful tip for preserving the sword.

But you deconstruct a sword to reconstruct its story. The next day, back in Franklin Park, and before sending the sword ahead, I had some photos taken of my grandfather with the relic he’ll never see again. I removed it from the scabbard, touching only the handle, and placed the gleaming blade in his age-lined roofer’s hands, having him pose as if it were an offering. It felt contrived, just as my Iejima pose would. But the contrast of the moment was real: the sword was an antique crafted well enough to shine for a thousand years, an object 500 years old having passed through generations of hands and conflicts, supported for a moment by weathered palms and fingers 400 years younger, hands soon to be gone but still part of the story.

I had the thought to wipe the surface down but ignored it. And when we were done, my grandfather moved one hand from the blade to the handle, supporting the sword’s weight while he moved his other off the blade to reach for the scabbard. He picked up the sheath, the tips of his straightened fingers the last mass to touch the steel before he slid the blade back in for the final time and sent it to a place he felt too weak to reach.

Kevin Chroust went to Japan in 2022 knowing as much about antique swords as he did about antique most things—very little. If he were to do the trip again, he’d bring luggage large enough to fit a three-foot sword rather than traveling a pandemic-restricted country as a foreigner with a debatably legal sword sticking out of a partially zipped backpack. Aside from returning to its rightful owners a sword that had been in his grandfather’s possession since World War II, the best part of the trip was holding a famously repatriated 800-year-old blade that looked like it was made on Tuesday. The worst part of the trip repeated itself daily whenever someone made a two-handed presentation of their business card to him and he was unable to reciprocate. His one complaint about his Japanese friends and contacts is no one told him that without cards he was risking repeated instances of inadequacy in the analogue contact information capital of the modern world. He now attends the occasional sword show, still without business cards, and pretentiously critiques the depiction of Japanese blades in U.S. pop culture.

Want more of Outside’s in-depth longform stories? Sign up for the Long Reads newsletter.