In March of this year, 58-year-old ultrarunner and cult hero Micah True—a.k.a. Caballo Blanco, the central character in Christopher McDougall’s Born to Run—died on a 12-mile training jog in the rugged Gila Wilderness of southwest New Mexico. It took friends and authorities four days of searching before they discovered his body, faceup and bruised, legs dangling in a creek. When the autopsy report was released, the Albuquerque coroner wrote that “Micah True died as a result of cardiomyopathy during exertion.” An enlarged left ventricle—the part of the heart that sends oxygenated blood to the body—likely caused a fatal arrhythmia. Caballo Blanco had died of natural causes. Or had he?

Micah True in Mexico in 2009

During a presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Sports Medicine in June, cardiologist James O’Keefe, director of the Preventive Cardiology Fellowship Program at Missouri’s Saint Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute, suggested that True’s death was anything but natural. Endurance athletes, O’Keefe proposed, are killing themselves with too much training. “The pathologic changes in the heart of this 58-year-old veteran extreme endurance athlete were likely manifestations of Pheidippides cardiomyopathy—a condition caused by chronic excessive endurance exercise,” O’Keefe and his colleagues wrote in an article later published in Missouri Medicine. The paper cited several recent studies and suggested that exercising vigorously for more than an hour a day eventually leads to scarring.

“Marathoners and Tour de France cyclists have incredibly fit cardiovascular systems,” O’Keefe says. “But it’s not an exercise pattern one should sustain for decades. It demands so much from the heart that you literally accelerate the aging process.”

O’Keefe’s findings grabbed headlines—and forced a good number of the estimated 15 million Americans who participate in endurance sports to reconsider their training regimens. Other experts, however, think O’Keefe’s warnings are overblown. “The idea that ultra activities put people at acute risk of sudden cardiac death is warmongering,” says Keith George, head of the Research Institute for Sport and Exercise Sciences at England’s Liverpool John Moores University. “It’s not supported by the evidence.”

In 2011, George published a study of 165 athletes who ran the Western States 100 ultramarathon in California. When he examined the participants, he found that their hearts were perfectly normal—normal for athletes, that is. “They have big hearts,” George says. “They have a heart of somebody maybe 10 or 15 years younger.”

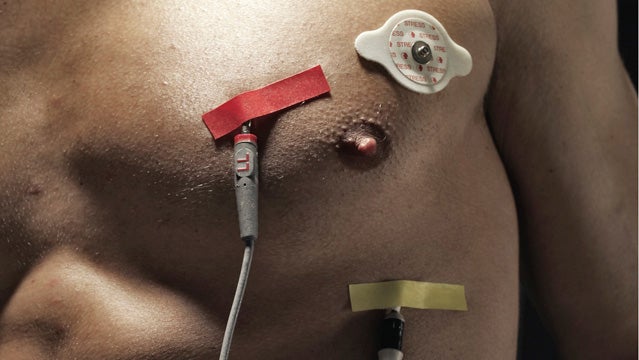

So-called athlete’s heart is a physiological adaptation in which the walls of the left ventricle grow thicker and the chamber larger to pump blood more efficiently. So far, evidence points to this condition being a natural outcome of intense training and reversible. However, George and his team did notice minor changes in runners that would indicate temporary cardiac damage. George believes these changes are “really small from a clinical perspective, and there’s absolutely no evidence that links them to sudden cardiac death.”

That’s precisely the link O’Keefe and his colleagues are suggesting, believing that several years of small changes can add up to permanent damage and deadly arrhythmias. What’s missing is any concrete evidence to support that view. For example, O’Keefe has yet to determine if an athlete must be genetically predisposed to scarring for it to occur. (In other words, high-volume endurance training might be fine for some and dangerous for others.) And even if scarring does occur among the entire population, it’s not clear whether endurance training exacerbated the issue. One small study O’Keefe cited, examining 102 male marathoners, found that incidences of scarring were “threefold higher than in age-matched control subjects,” but similar studies have found much smaller differences, suggesting that even if there is a risk of scarring from endurance training, it’s slight.

George believes that deaths like True’s and Jim Fixx’s—who popularized jogging with the bestselling Complete Book of Running and died of a heart attack after a run in 1984—are exaggerating the gravity of the issue because they receive so much media attention. “It is a relatively small problem, it’s just a high-profile problem,” says George.

Where does all this leave endurance athletes concerned about heart health? O’Keefe recommends running no more than 20 miles and training no more than seven hours a week. But, he says, extra effort is “better than being a couch potato.” And he still recommends all-day activities outdoors, “just not at high intensity for uninterrupted periods.”

Others see no reason for you to strike marathons from your to-do list. “With endurance, the question is: Are we going too far?” George says. “Most of the data suggests the answer is no. There will always be the guy who dies in the bush or at the end of a marathon. Those people are just exceptionally unlucky.”