The Thieves Didn’t Leave Fingerprints. Detectives Used Tree DNA To Convict Them Instead.

Timber thieves are a slippery bunch. Here's how cops uncovered an underground criminal ring in spanning the Pacific Northwest and cracked down to protect the state's ancient trees.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! Subscribe today.

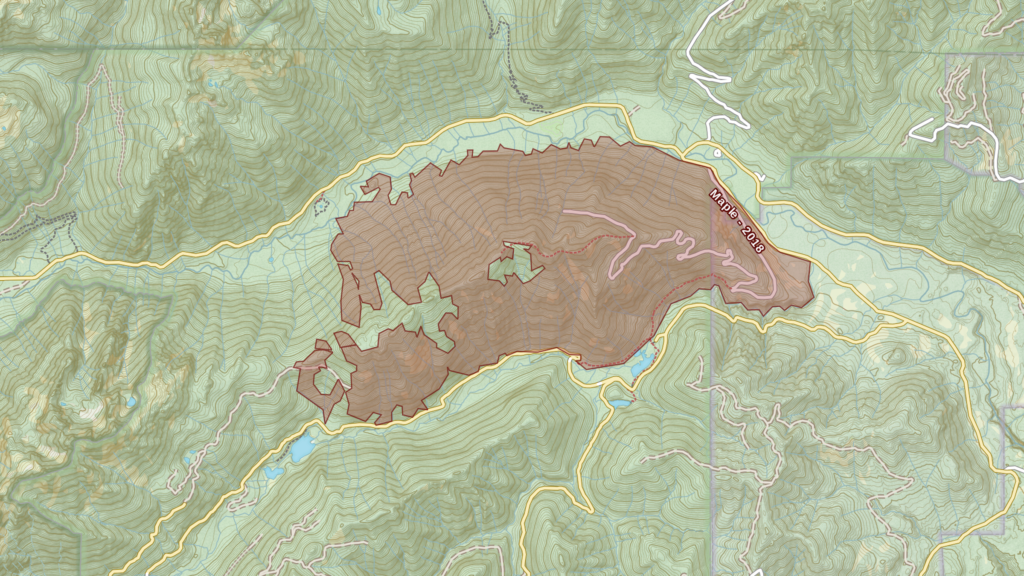

Deep in the night on August 4, 2018, a trio of timber cutters bushwhacked into a steep valley thick with brush, wearing headlamps and carrying a chainsaw, gas can, and a slew of felling tools. Their target, a trifurcated, mossy bigleaf maple, towered above Jefferson Creek, which gurgled down the narrow ravine floor that drains the Olympic National Forest’s Elk Lake. Justin Wilke, the band’s captain, had discovered the massive tree the day before and dubbed her “Bertha.”

Wilke had established three dispersed campsites in the Elk Lake vicinity, some 20 miles from the nearest town of Hoodsport, Washington, over the previous weeks. By day he scouted for the most prime bigleaf maples. He had illegally felled at least three in the area since April, but he considered Bertha the mother tree.

A carpenter by trade, Wilke, then 36, dabbled in odd jobs in construction, as a mechanic, on fishing boats, and in canneries, but like many across the peninsula’s scattered hamlets, he’d been a logger since his hands were sure enough to wield a chainsaw. A tattoo the length of his left arm read “West Coast Loggers,” his tribute to a heritage that began with his grandfather.

Honest work had grown scarce. Wilke and his girlfriend were camping on a friend’s property just outside the national forest to trim expenses and lived on his earnings from cutting illegal firewood and selling poached maple. The situation wasn’t tenable. He was hungry, and he needed a windfall.

Closing in on Bertha in the darkness alongside Wilke were Shawn “Thor” Williams and Lucas Chapman. Thor had just sprung from a stint in prison two weeks earlier. A 47-year-old union framer, Thor had also dabbled as an MMA fighter and debt collector and carried a litany of past convictions ranging from assault and burglary to unlawful imprisonment. He hoped the job would deliver him back to his daughter and sometimes-girlfriend in California. Chapman, 35, was Wilke’s gopher, hired primarily to watch the campsites during the operation. The three were high on methamphetamines.

Though the relative humidity that night hovered around 75 percent, the air a pleasant 60 degrees, rainfall had been unusually sparse that summer. Higher than average temperatures ushered the typically wet Olympic region into a moderate drought. Smoke from various wildfires in British Columbia had clouded the air throughout the summer.

Bertha held a bee’s nest in a hollow at the base of her trunk that made chainsaw work problematic. “I’m not going over there,” Thor, who was allergic to bees, protested. At their campsite two days earlier, he’d been stung on the hand and suffered mild anaphylaxis after he sipped a can of Four Loko with a bee in it. “I’ll take care of it,” Wilke said.

Accounts of who did what next vary, but someone pulled out a can of wasp killer and sprayed the hive to little effect, then doused it in gasoline and lit a match. The offended bees clouded the air. Flames sprouted up Bertha’s trunk and expanded in the underbrush at her roots.

For the next hour, Wilke, Thor, and Chapman beat the burgeoning fire with sticks, kicked dirt over it, and used Gatorade bottles to quench its tongues with creekwater. “Let’s go,” Wilke finally ordered. “It’s out.”

By the time the poachers left, cold and wet from splashing in the waist-deep river, all clear signs of flame had vanished. The first gauzy motes of dawn lightened the sky. In the leafy silence that followed the thwarted thieves’ retreat, beneath the duff at Bertha’s roots, still-hot embers smoldered and crept through the forest, invisible but surging with the breaking day.