Rumor has it that Roland Brunner, like other privately trained Swiss helicopter pilots, can pour wine into a glass on the ground from a bottle attached to the chopper’s landing skids. It’s a fitting claim—and, given the situation, one I hope is well-founded.

Access to Resources

SwisSKIsafari has three Ultimate Journey trips scheduled for 2006: March 19–23, March 26–30, and April 1–5. ,900 per person, including accommodations, helicopter flights, and most meals, which, of course, include ample samplings of local wines; 011-41-79-239-4152, www.swisskisafari.com. Getting there} Swiss International Air Lines—legendary for its top-notch in-flight service and impressive gourmet meals (sometimes including chocolate)—flies daily from New York’s JFK to Geneva (877-359-7947, www.swiss.com). From Geneva, you’ll have to catch those famously punctual trains (they stop inside the airport) for a two-and-a-half-hour ride to the group rendezvous in Verbier (w… BIER-30: Right on time for a post–piste ale and a pork ingot

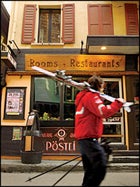

BIER-30: Right on time for a post–piste ale and a pork ingot

It’s a sunny afternoon in Arolla, a chalet-and-cowbell burg tucked into the alabaster folds of the Swiss Alps, and the staccato beat of Brunner’s helicopter pounds through the valley. Two hours ago, the pilot left my skis and me on the enamel of a toothy, 12,000-foot peak. From there, Sé;bastien Devrient, a chiseled French-American guide, led the way down a big-mountain line of bellowing crevasses, powder-rich bowls, and steep fields of buttery corn. Now, some 6,000 vertical feet later, my legs are quivering from hot jags of lactic burn, and my belly is full. I’m standing in a small field, before a table groaning with meat and little pickles. A dozen wine bottles—emptied earlier, over lunch, by me and several others—stand in neat rows. Suddenly, Brunner rockets into sight, pulls the chopper nearly vertical, turns around, and dive-bombs straight toward us.

With whirling blades fast approaching, I make a quick assessment of the situation. On the pro side, I’ve flown with Brunner once already today: He certainly demonstrated ultimate control of the bird as he whipped us over to a macro view of the Matterhorn, Bec des Rosses, and Mont Fort. Most of the chopper pilots I’ve met are grizzled vets with thick thumbs and cool composures earned in ‘Nam. I don’t know much yet about Brunner–a 40-something with curly brown hair and furry cowboy boots—but he looks like a yahoo party boy. I chalk the stunt up as a con and get out of the way.

No need: At the last minute, Brunner pulls the chopper’s nose up and drifts in as smooth as chocolate fondue, touching down on a small landing pad near the table. There’s more skiing to be had, and Brunner is our lift. With the backcountry run out of the way, it’s time to wallow in the pleasures of the front country—leisurely runs on wide in-bounds blues at Zermatt (about two hours east by car, it’s only 20 minutes away for us whirlybird passengers), some cold lagers at a stüli, perhaps, and a fine meal of goose-liver mousse before bed.

And so begins a several-day pattern of blending off-piste adventure with slopeside European sumptuousness. Before I load into the helicopter, I wrap up a few slices of organic pork ingots, stowing them in my pocket for the flight—just because I can.

THE SWISS ARE FOND OF SAYING they use more helicopters per capita than any other nation, and not just to decant wine. Nevertheless, heli-skiing trips in Switzerland have traditionally amounted to a daylong sideshow act tacked on to a lift-skiing vacation at the big resorts. Although their country is in the center of a 660-mile arc that traces some of the world’s most impressive peaks, when the Swiss have wanted a longer heli-skiing trip, they’ve flown to Canada.

At least, that’s the way it was. This winter, for the first time, gravity hounds looking for multi-day heli-skiing in the Alps can sign up to experience SwisSkiSafari’s Ultimate Journey, a four-day, five-night, fine-wine-and-slide luxury tour that zips skiers around the country’s top resorts in privately chartered B3’s and Bell 407’s. You start in Verbier (about 100 miles east of Geneva), then fly east to Zermatt and Saas Fee, making backcountry drops in between—wherever the snow is best. Doing 5,000- to 7,000-vertical-foot runs in a single push can hurt, but returning every evening to top-notch digs and massages blunts the pain.

An ultimate day goes like this: After un petit dé;jeuner of muesli and juice, I ride the lifts at Verbier to the landing zone, which is right on the slopes. Brunner swoops in, and up we go—to the top of a peak like the 12,454-foot Pigne d’Arolla, on the classic Haute Route from Zermatt to Chamonix.

The backcountry skiing is hardcore lite: fun bowls, glades, and a few long traverses on glaciers. We wear harnesses for rescues, should someone fall into a crevasse. For hours, 33-year-old guide Devrient and 36-year-old Danielle Stynes, an Australian snowboarder and skier and the company’s owner, lead no more than eight people through knee-deep powder that turns to crust, then to corn soup as we go lower. L’hé;lico arrives again, and off we fly to a wine-and-cheese lunch at, say, a slopeside patio in Saas Fee, where everyone speaks Swiss-German. Come afternoon, we’ll ride lifts with Devrient and Stynes (who show us secret in-bounds stashes the Swiss don’t hit), drink more wein, and spend the night under silky-soft European duvets. The next day, we’ll do everything all over again—on different mountains and at different resorts. There’s rarely a down day, no endless games of Scrabble within the confines of a lodge.

“Even if the skies are cloudy, the helicopter can fly lower through the valleys,” says Devrient one night, over beers in a cozy Zermatt stüli. “We can even go into Italy, have spaghetti, have some skiing. No one can guarantee excellent skiing all of the time. But we can guarantee excellent traveling. Just flying around in a helicopter is fun.”

But that’s not quite why this trip is so cool.

Let’s be frank. Though beautiful, Switzerland has long had a reputation for being dull. While France racked up urban-chicdom and five weeks of paid annual vacation, Switzerland’s 7.2 million people were busy obsessing on cutlery, punctuality, and self-cleaning toilet seats. This nation of cheesemakers, barely the size of Vermont and New Hampshire combined, nonetheless enjoys great geologic blessings: It contains some of the highest peaks in the Alps. Yet all the trains, huts, and gondolas the Swiss government has strung through these mountains—for 30 years, lifts and trams have been gobbling up about $280 million in taxpayer money—have done relatively little to give terra-bound travelers easy access to a wilderness that’s as jagged and sheer as anything in Alaska. The tantalizing fact is that immense, snowy playgrounds sprawl just beyond cobblestone streets, and you can’t get there.

“Those mountains are still super-remote and rugged. Just to get back into them, you need several days,” says pro skier Chris Anthony, who runs similar trips, but without the flights, in Italy. “Helicopters in Switzerland open up all kinds of opportunities.”

In other words, once the bird has lifted off, tiny Switzerland suddenly becomes big and exotic. Just make sure you’re on time for the flights.

WE’RE RUNNING a little late today—an evening of wine tasting in Verbier turned, predictably, into a long night of wine guzzling–but Devrient still gets us to the landing zone almost on time. A group of Frenchmen who scheduled a single drop somewhere insists on going first. Merde!

“Tim—up front!” shouts Stynes. Brunner has returned. So that’s where I sit.

Up we go, Brunner taking us on a roller-coaster ride around seracs, over glaciers, and up cliffs. He drops us on the Pigne d’Arolla, with nowhere to go but down. For more than two hours, that’s what we do, converting thousands of vertical feet into fresh tracks, sidestepping through crevasse fields, and pausing to watch faraway glaciers calve. I’ve skied big landscapes in Alaska and Canada. I even lived in Switzerland for a year. But the scenery here—ragged peaks piercing deep-blue skies over valleys so green they inspire thoughts of frolicking—makes me entertain fantasies of staying forever.

In Arolla, a tiny village 6,000 feet below the peak, a local French-speaking butcher waits for us on a patch of grass in a snowy field. While the Inuit have about two dozen words for snow, the Swiss, with their four languages, have at least as many words for meat. Our butcher’s picnic table may as well be an illustrated dictionary of them all.

“You try?” Monsieur le Boucher asks, opening a bottle of Dôle—a red from Valais, the name for this part of southwestern Switzerland.

“Fruity, with a chalky nose,” I say jokingly.

“Qu’est-ce que c’est—chaqué;nose?” demands the confounded Boucher.

“Bon!” I say. “Everything is bon!”

“Oui! Trè;s bon!” he erupts, topping off my glass with wine in celebration of transatlantic understanding.

Party Boy rockets into sight and does his stunt thing. This time, my pork ingots and I sit in the back. The helicopter plunks us down at about 10,180 feet—at the top of the Unterrothorn, a peak above Zermatt. From there, we spend the afternoon skiing lift-accessed corn, eventually sliding down to the Germanophone Heidi Land of electric cars and pubs.

After a sound sleep at the Grand Hotel Zermatterhof, an 84-room palace of nut and cherry wood with granite bathrooms and views of the Matterhorn off the deck, we hit Italy. Brunner can’t fly there, so an Italian pilot lands on the slopes—fully thrashing a lady in an all-white ski suit with a fur collar, who struggles to stay upright in the torrent. For the second time in 24 hours, I’m flying around the Matterhorn and near the toothy spires of the Dent Blanche, the Weisshorn, and the Dent d’Hé;rens. Not ten minutes later, I’m standing on the Tête de Valpelline—a 12,464-foot peak straddling the Swiss border. The snow is light, fluffy, and practically endless. It was good yesterday, but this is the best I’ve seen.

No longer able to contain my giddiness, I ski to the sound of my own whoops. We pass a group skinning up on randonné;e gear, and they no doubt curse my big, fat snakes for devouring the runs they’ve been working hours to get to. A longtime observer of “earn-your-turns” ethics, I feel their pain. But my turns are so easy, I feel only slightly guilty.

Actually, I don’t feel guilty at all. As I draw closer, I pull my wide, gluttonous turns into a modest series of prissy S’s. I pass the group in an exaggerated telemark stance, hoping they’ll see my freeheel and, oblivious to the helicopter circling overhead, think that I, too, hiked up. They aren’t taken in. Oh, well: I hog the snow again and consider calling them suckers—just because I can. But that wouldn’t be very bon.