Deb Haaland’s Long Game for Victory

It’s not easy being a progressive who works for a middle-of-the-road president. Mark Sundeen sizes up the interior secretary’s first year in office—which has been a disappointment to climate-change activists—and decides she’s most likely to make a mark through a historic reckoning over the U.S. government’s shameful running of Native American boarding schools.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! Subscribe today.

In February 2021, when President-elect Joe Biden nominated Deb Haaland to become the 54th secretary of the interior, the left and right staked out familiar turf. A one-term Democratic congresswoman from Albuquerque, New Mexico, Haaland had become a darling to environmentalists. She supported the Green New Deal, called for a fracking ban on public lands, and tweeted out progressive red meat like “Republicans don’t believe in science.”

GOP legislators all but fainted on the rotunda floor but were revived with smelling salts long enough to foresee the end of the oil industry and what one of them called “our way of life.” Fifteen House members urged Biden to withdraw the nomination, labeling it “a direct threat to working men and women.” Senator Steve Daines of Montana, a member of the committee that would examine Haaland’s qualifications for the job, denounced her as “radical” twice in the same press release. “Unless my concerns are addressed,” he warned, “I will block her nomination.”

Why all the drama? As someone who has lived in and written about the American West for 30 years, I can tell you that the secretary of the interior, whose main role is overseeing the National Park Service and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), isn’t usually a memorable figure. The vast majority of Americans who aren’t mine owners or professional environmentalists would be hard-pressed to recall a single one of them by name. Dirk Kempthorne? Ryan Zinke? Sally Jewell? None were household figures like former secretaries of state Hillary Clinton and Colin Powell.

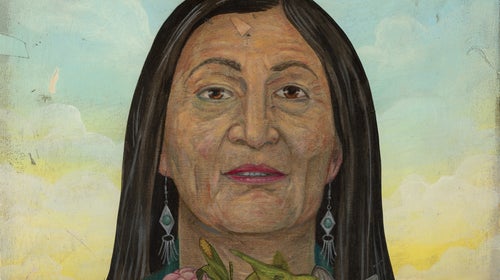

If the conservative goal was to marginalize Haaland as an extremist, it backfired. Instead she blossomed into a sort of folk hero, complete with hashtags, puff pieces in food magazines, and cover shoots for fashion glossies alongside J.Lo and Rihanna—more like a Top Chef all-star than one of the parade of faceless bureaucrats who inhabit the federal Cabinet. (Sorry, Tom Vilsack.) This is partly because Haaland, a Native American who’s an enrolled member of New Mexico’s Laguna Pueblo, had already qualified as a bona fide historic figure. In 2017, along with Sharice Davids of Kansas, she was one of the first Native women elected to Congress. Under Biden, she became the first Native American—man or woman—nominated to a Cabinet position.

The significance of the Cabinet nomination was immediately apparent. When it was announced, Winona LaDuke, executive director of Honor the Earth and a two-time Green Party vice presidential candidate, applauded the move and said, “It’s time Native people are in a position to take care of Mother Earth. We know how to do it.”

Julian Brave NoiseCat, an activist and author who led a campaign to put Haaland on Biden’s radar, was thrilled when she was picked. “She embodies this grassroots movement of Indigenous leaders on environmental issues,” he told me. “She was at Standing Rock cooking green chile and tortillas for water protectors.”

Now entering her second year as interior secretary, Haaland has frequently disappointed the left, which wanted a climate-justice crusader that so far it hasn’t gotten, and confounded the right, which fantasized about a bottle-throwing Antifa block captain it could keep bashing politically. But her environmental decisions to date have taken a path right down the unexciting middle, which in retrospect isn’t too surprising: she works for a moderate president.

While conservatives may have railed that this likable woman of color was a shill for eco-saboteurs, I’m here to argue something else: that the real threat to the status quo is having a powerful Native American demanding justice for Native Americans. Somewhat overlooked in the spat between the Keep Oil in the Ground crowd and the Drill, Baby, Drillers—groups that both tend to be white—was the fact that Haaland would also oversee the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), one of the most damaging and frankly racist offices in the history of American government. On Native issues, Haaland has moved swiftly to reckon with centuries of genocide and stolen land. In this arena, she could prove to be a more transformational figure—a blunt corrective for a nation that still does not know its own history—than anything conservatives feared or progressives imagined.