Evan Dunfee’s bronze medal at the 2019 World Championships in Doha was a triumph of persistence, patience, and toughness—and also of plumbing and refrigeration. Facing muggy race conditions in Qatar of 88 degrees Fahrenheit with 75 percent humidity, the Canadian 50K racewalker spent ten minutes in an ice bath shortly before the race, then donned an ice towel while waiting for the start. During the race, he hit up the drink stations no less than 74 times over the course of less than four hours, grabbing water bottles, sponges, ice-cooled hats and towels, and “neck sausages” full of ice.

It worked: Dunfee’s core temperature, measured by an ingestible pill provided as part of a World Athletics study whose results have just been published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine, stayed relatively stable below about 102 degrees Fahrenheit for most of the race. That’s hot but sustainable—and it meant that, with 5K to go, Dunfee was feeling good enough to accelerate as his rivals wilted in the heat. He made up two minutes on the eventual fourth-place finisher to snag a medal while his core temperature spiked to 104 degrees (as he and his physiologist Trent Stellingwerff recount in a fascinating joint online talk about their Doha preparations and experience).

Not everyone fared as well in the unusually hot conditions. In the women’s marathon the night before, only 40 of the 70 starters even finished the race. The World Athletics study, conducted by a large multi-national team led by Sebastien Racinais of Doha’s Aspetar Orthopaedic and Sports Medicine Hospital, collected data from 83 athletes in the marathon and racewalk events. The subjects filled out surveys on their hydration and cooling plans, swallowed pills to track their core temperature during competition, and had infrared cameras measure their skin temperature immediately before and after racing.

The results offer a rare inside look at how elite athletes handle the controversial challenges of hydration and cooling in the heat of competition, and how well their methods work. Here are some of the highlights.

(Almost) Everyone Drank

There’s an ongoing debate about the merits of following a pre-planned hydration strategy versus just drinking when you’re thirsty. In this case, 93 percent of the athletes had a specific pre-planned strategy. The racewalkers planned to drink the most: even those in the shorter 20K walk planned to down, on average, 1.1 liters of water per hour. The marathoners planned just 0.7 liters per hour, likely due to the fact that it’s harder to drink while running, and more uncomfortable to have fluids sloshing around with running’s up-and-down motion.

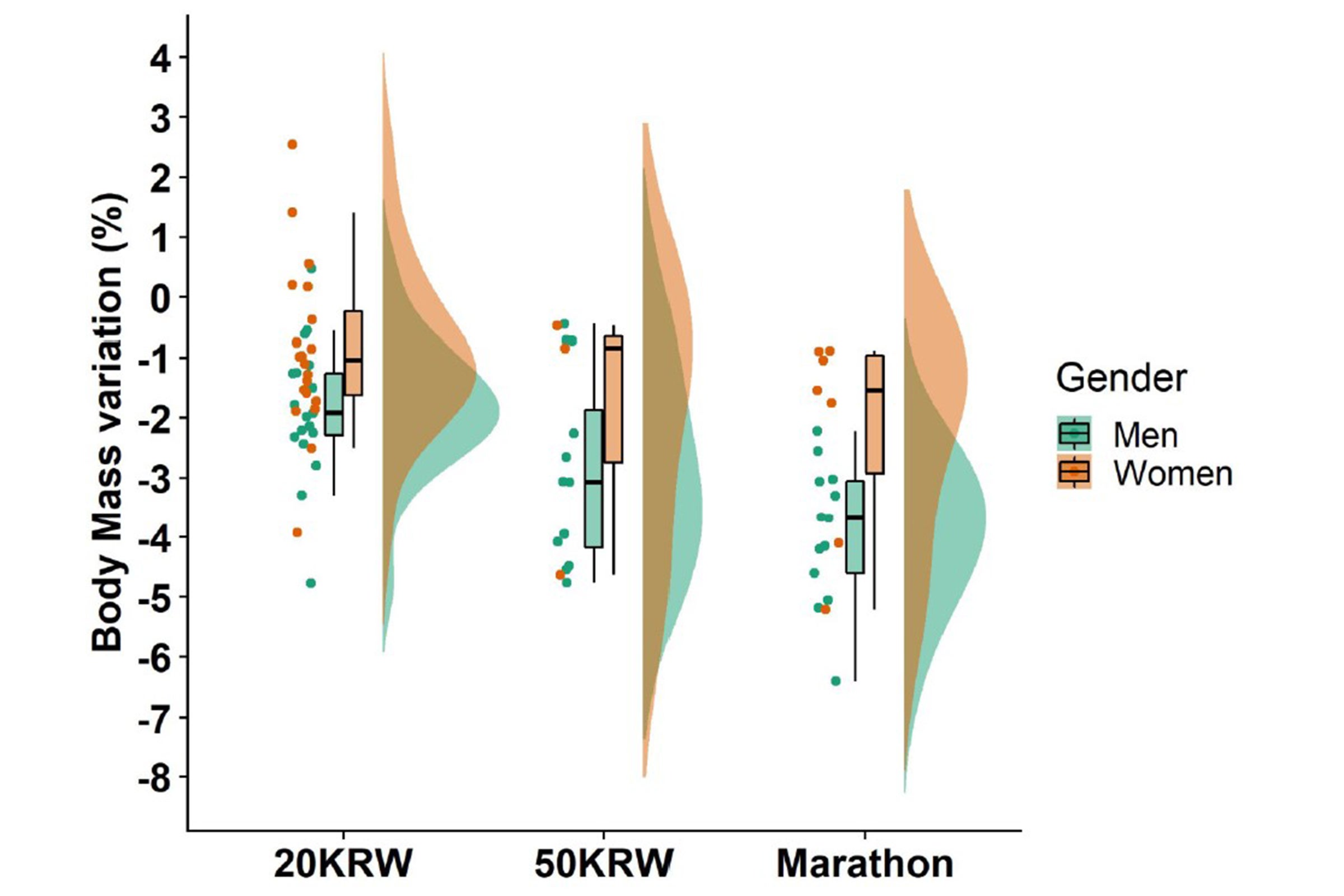

Pre- and post-race weighings showed that the athletes lost an average of 2.2 percent of their starting body mass. Again, there was a difference between racewalkers, who averaged 1.4 percent in the 20K and 2.7 percent in the 50K, and runners, who averaged 3.3 percent.

Here’s how the individual data points for weight loss looked. The vertical axis shows how much weight each athlete lost (negative numbers) or gained (positive numbers) as a percentage of pre-race weight for the three events studied. Each dot represents an individual athlete; the bars and curves show the approximate distribution of those values for men versus women.

Interestingly, six of the 20K racewalkers actually gained weight during their race. There was plenty of concern about Doha’s hot conditions, so it appears that some of the athletes were a little too spooked by the risk of dehydration. Drinking that much is unlikely to be helpful. That said, there was no significant relationship between how much weight an athlete lost (or gained) and how they performed, either in absolute terms or relative to their personal best.

At the other end of the spectrum, two of the 29 marathoners in the study said they weren’t going to drink anything at all. Both runners were from Africa; previous research into the drinking habits of African marathoners has noted that some choose to drink less than sports nutritionists suggest. That was also one of the surprising revelations during Nike’s Breaking2 project: superstar runners like Lelisa Desisa and Zersenay Tadese were used to drinking virtually nothing during marathons. In this case, though, the two non-drinkers both finished in the back half of the field. When it’s this hot, not drinking at all seems like a losing strategy.

Pre-Cooling (Maybe) Worked

Eighty percent of the athletes used pre-cooling techniques to lower their body temperature prior to starting the race. The most popular tools were ice vests, used by 53 percent of the athletes, and cold towels, used by 45 percent. Next were neck collars, ice-slurry drinks, and cold tubs.

Most athletes also planned mid-race cooling, primarily by dumping water on their heads. Some, like Dunfee, also opted for neck collars and icy hats. Top fashion points go to the German racewalkers, who appeared to be paying homage to the famous white kepi of the French Foreign Legion.

The only technique that had a significant effect on pre-race core temperature, as measured by the ingestible pills, was ice vests: those using one started the race with a temperature of 99.5 F, while those without started at 100.0 F. The ice-vest wearers placed higher than the non-wearers, but that’s probably because the top athletes were more likely to have fancy gadgets. There was no difference in their performance relative to their pre-race bests.

On the other hand, athletes who started the race with lower skin temperatures tend to record faster times relative to their pre-race bests and were also less likely to drop out. The skin temperature was an average of spot measurements calculated from 26 different “regions of interest” around the body, from the head down to the lower legs, using the infrared camera. One possibility is that lower skin temperature creates a greater difference between core and surface temperature, making it easier to dump excess internal heat once you start exercising.

Overall, there were so many different cooling strategies relative to the small number of athletes in the study that it’s impossible to draw firm conclusions about what worked and what didn’t. There has been plenty of laboratory research suggesting that pre-cooling really does enhance endurance performance in hot conditions. I’d take these findings—ice vests lower core temperature, skin temperature correlates with performance—as tentative but not conclusive hints that the lab findings really do translate to the real world.

That’s certainly Dunfee’s take. “There were only one or two points in the race where I felt hot,” he told Canadian Running after his race. “I one-hundred percent attribute my success to this strategy.” For many athletes, Doha 2019 was a dress rehearsal for the expected heat at Tokyo 2020. We still don’t know what Tokyo 2021 will look like (if it happens), but it’s a safe bet that athletes from around the world will be looking at these findings closely—and, perhaps, taking a page from Dunfee’s book.

For more Sweat Science, join me on Twitter and Facebook, sign up for the email newsletter, and check out my book Endure: Mind, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human Performance.