This Monday, the best riders in the world will convene in Colorado to race the USA Pro Cycling Challenge, a 683-mile, seven-day stage race. And we’re psyched. From Tour de France winner Chris Froome to playboy and two-time Tour Green Jersey winner Peter Sagan, our favorite riders will be within a day’s drive of Outside’s Santa Fe headquarters.

The Future of Anti-Doping

Forget blood tests, the future of anti-doping may be all psychological.Some of us will be making the trip up to Aspen, while others will be cheering from their living rooms. But amid all the excitment, there’s a strong undercurrent of suspicion. Froome’s win was so dominating at the Tour, and the questions about his doping so relentless, that Froome’s director on Sky Pro Cycling, Sir Dave Brailsford, grabbed the microphone at a press conference in July to confront the media:

“We’ve wracked our brains thinking about ways we can satisfy people and make these questions go away,” he said. “Why don’t you collectively get organized and you tell me what we could do, so you wouldn’t have to ask the question?

Nobody in the room had an answer—then or now. But it’s a question that has been asked—and answered before. On the eve of the 2006 Tour, 13 riders were expelled from the race, amoung them Jan Ullrich, Ivan Basso, and Alberto Contador. With the Tour’s reputation in tatters, the UCI, the sport’s governing body, moved to take a hardline against doping, instituing the biological passport in 2007.

The goal was to create a blood and urine profile for each professional cyclist that could be used to spot irregularities. Anti-doping specialists know how a cyclist’s body should respond to a long race or a bout of training. By establishing a baseline and regularly retesting riders, specialists could flag blood or urine results that didn’t match their expectations. An irregular value would lead to additional testing and in rare circumstances a suspension without a positive blood or urine test.

Over the last six years, the system has worked—sort of. Eight riders have been caught and suspended on the basis of the biological passport data. And in 2011, the Court of Arbitration for Sport, the court of last resort in doping cases, gave their nod of approval, validating two suspensions based on biological passport data alone.

Outrageous or sloppy cases of doping are now easy to spot. If riders are cheating and getting away with it, they’re no longer take large doses of EPO or even the micro-doses of recent years. Instead, riders are resorting to masking doses, capable of yielding only .25-.5 w/kg boost at 40-minute threshold power. Doping can still win races, but clean riders have some hope.

The biological passport puts cycling leagues ahead of many sports, but it’s far from a foolproof solution. Dopers are still slipping through, and many observers and watchdogs are blaming the UCI. Anti-doping experts, as well as former dopers like Michael Rasmussen, who was expelled from the 2007 Tour, say that these new subtle and systematic approaches to cheating are still undetectable. The program “perhaps puts a damper on things,” Rasmussen says, “but it's absolutely no guarantee that cyclists do not undergo blood transfusions along the way.”

More criticism has come from within the passport program itself. In 2012, Dr. Michael Ashenden, one of nine experts who reviewed rider data for the UCI, resigned from the program, saying that he had “noticed a significant gap between tests in some of the profiles.” What sounds like muted criticism was really an attack on the UCI’s credibility. For the passport to work, athletes need to be regularly tested. Reduce the number of tests, and the passport becomes nothing but a front, a publicity tool.

Lance Armstrong may have fallen, but can an organization with the same leadership in place that accepted, between 2002 and 2005, a total of $125,000 in “donations” from the discredited rider be truly trusted to root-out doping? For many, the answer was no. Into the void of credibility, organizations like Bike Pure and the Movement for Credible Cycling emerged, promising to help clean-up cycling by reforming the UCI and holding teams to a higher standard.

But their efforts have stalled. Bike Pure, an organization that aims to protect the integrity of cycling, has grown as a business but has done little more than sell rubber bracelets. The Movement for Credible Cycling, a union of teams dedicated to clean cycling, now includes 11 of 19 World Tour teams, but has failed to institute truly exacting or revolutionary demands. And by including known (and unrepentant) dopers like Alexander Vinokourov, the movement has compromised its credibility even as it’s grown.

Ahead of this year’s Tour, Bike Pure reentered the conversation by removing Froome from its list of endorsed riders. The timing struck many as exploitative, but their complaint—that he failed to release his power data—touched a nerve in the once-fringe world of power analysis. Pundits claimed that by examining Froome’s power data, they could prove that he was clean—or dirty. But Team Sky refused, saying that power data could be misinterpreted, that armchair experts and opponents couldn’t be trusted with the numbers.

It’s hard to blame them. This kind of information can be twisted. When Bradley Wiggins, then riding for Team Garmin, released his blood data from the 2009 Tour, it didn’t exactly reassure his fans; rather, it opened up new questions and criticism that have yet to relent. When it comes to power numbers, Sky has taken a conservative approach in the fight against doping. But the team—despite appearances—has done more than most to create a clean environment.

They’ve released some of Froome’s power data to French daily L’Equipe, shared his TUE (medical exemptions to use prohibited substances) history, and fired team doctor Geert Leinders along with two members of their coaching staff for past involvement in doping.

Sky may be winning the fight behind closed doors, but they’re losing the PR battle. Froome didn’t just win the Tour, he dominated it, climbing at speeds not seen since the heyday of the doping era. And a cadre of anti-doping experts led by people like Michael Puchowicz M.D., who authors an anti-doping blog called VeloClinic, have been on the attack, incredulous that even a well-trained, preternaturally talented rider can exceed the “enhanced” times of yesteryear.

This kind of analysis has proven reliable when compared to actual data taken from the racers. But even the partial release of Froome’s power data to the public has not quelled the critics. En route to his 2006 Tour victory, Floyd Landis made his training and power data public, and still tested positive. Even Armstrong shared some blood data ahead of his 2009 comeback. Many have since noticed irregularities with his values, but at the time, many experts found them within the realm of normal.

If the experts are to be trusted, the cheats will always slip through. But the retroactive testing from the 1998 Tour and the subsequent fallout—at least four former riders have lost their jobs—shows that time may be anti-doping’s strongest ally. When Rasmussen came clean, he made one telling comment: “You just have to remember that even though the biological passport may not be the perfect solution, the truth will come out at one time or another. Even though I doped for 13 years and avoided being caught, the truth is not hidden at the end.”

It’s painful to admit as a fan, but we can’t prove innocence—at least in the present. And only sometimes can we even agree an athlete is guilty. This leaves us in a precarious position. We can either agree with Brailsford that Sky has done everything within reason, or we can say they haven’t gone far enough—and turn to extreme measures, of which there are no shortage: Four-time Tour stage winner Marcel Kittel recently underwent a lie detector test.

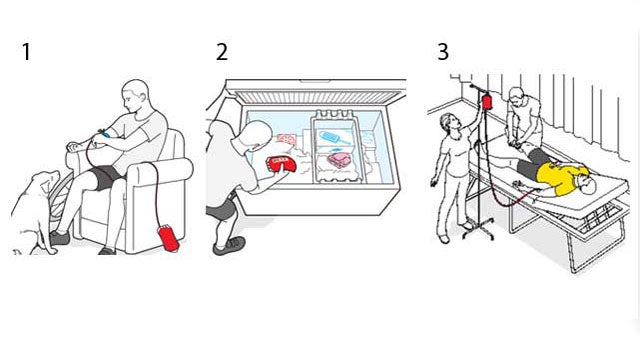

It might just be the beginning of such measures. Ian Dille, a former professional cyclist and journalist who writes often about doping issues in the sport, suggests the future of anti-doping may go so far as to include psychological testing and brain scans.

Cycling has been working hard to repair its reputation and as fans, we long for the day when we can watch such talented and committed athletes, like the ones who will be hammering the Colorado highways this week, without suspicion. For your consideration, here are several more steps the sport can take.

—Clean house at the UCI. In the upcoming UCI presidential election, riders and teams should vocally support a candidate with a clean past who makes pursuing a more transparent future the cornerstone of his campaign. The organizations corrupt leadership that aided and abetted doping must go.

—Strengthen the Movement for Credible Cycling. To prove their seriousness in the fight against doping, Team Sky should join the Movement for Credible Cycling and push to strengthen the organization’s standing. Teams like Astana, which recently signed ex-doper Franco Pellizotti in violation of the MPCC’s internal rules, should be booted from the organization. And under new leadership, the UCI should push race organizers to favor MPCC teams when selecting entrants.

—The UCI should cede all anti-doping responsibilities to WADA or other outside agencies. Throughout its history, the UCI has turned a blind eye to doping. Allowing the organization to remain in control of anti-doping efforts is a farcical. As detailed analysis done on the insider cycling site Cyclismas shows, it’s likely that the UCI has optimized testing to catch the fewest number of cheats. On outside organization will likely catch more dopers on the same number of tests than the biased or criminally incompetent UCI.

—The Biopassport needs to be reexamined, made more public and, if possible, strengthened by the inclusion of power data. As the Economist noted and Outside columnist and Mayo Clinic researcher Michael Joyner reiterated, transparency is not just a buzz-word—and it’s not just for the spectators. By showing professionals that the top riders are being tested and put to scrutiny, the incentives to dope decrease. Public numbers will also allow experts and watchdogs to crowd-source anti-doping efforts by flagging high-normal values, test results that don't result in positive readings but are highly suspicious and damning.

—Institute regular retroactive testing. The tests of today will always remain beatable. But the results of the 1998 retroactive testing show that what’s currently cutting-edge will one-day likely be easily detectable. By retesting samples and instituting strong fines for doping, the sport may be able to persuade riders that doping is a poor choice.

See you in Colorado.