How to Find the Perfect Adventure Buddy

Work. laundry. The weather. There are so many excuses to not get out there. But when you have a solid adventure buddy, the answer is always yes.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! Subscribe today.

There are times, more than I’d care to admit, an hour and a half into a trainer ride in my freezing garage, staring at my bike avatar move through virtual landscapes of Zwift, when my gear is growing moss and the walls are closing in the way do at Disney’s Haunted Mansion ride, that I suddenly feel the urge to shed the cloying comforts of home and go for some long trek through a foreign landscape.

If only, I’ve often thought, I had an Adventure Buddy—someone who would always be there, nodding along as I detailed my latest hazily conceptualized scheme: I just read about the most remote pub in the UK. They’ll buy you a beer if you hike in. It takes a few days. You up for it? To complicate things, my mind never seems to drift to the local, the achievable (say, a day-hike in the Poconos) for which I might actually drum up a companion. I generate quixotic ideas that call for veritable Sancho Panzas.

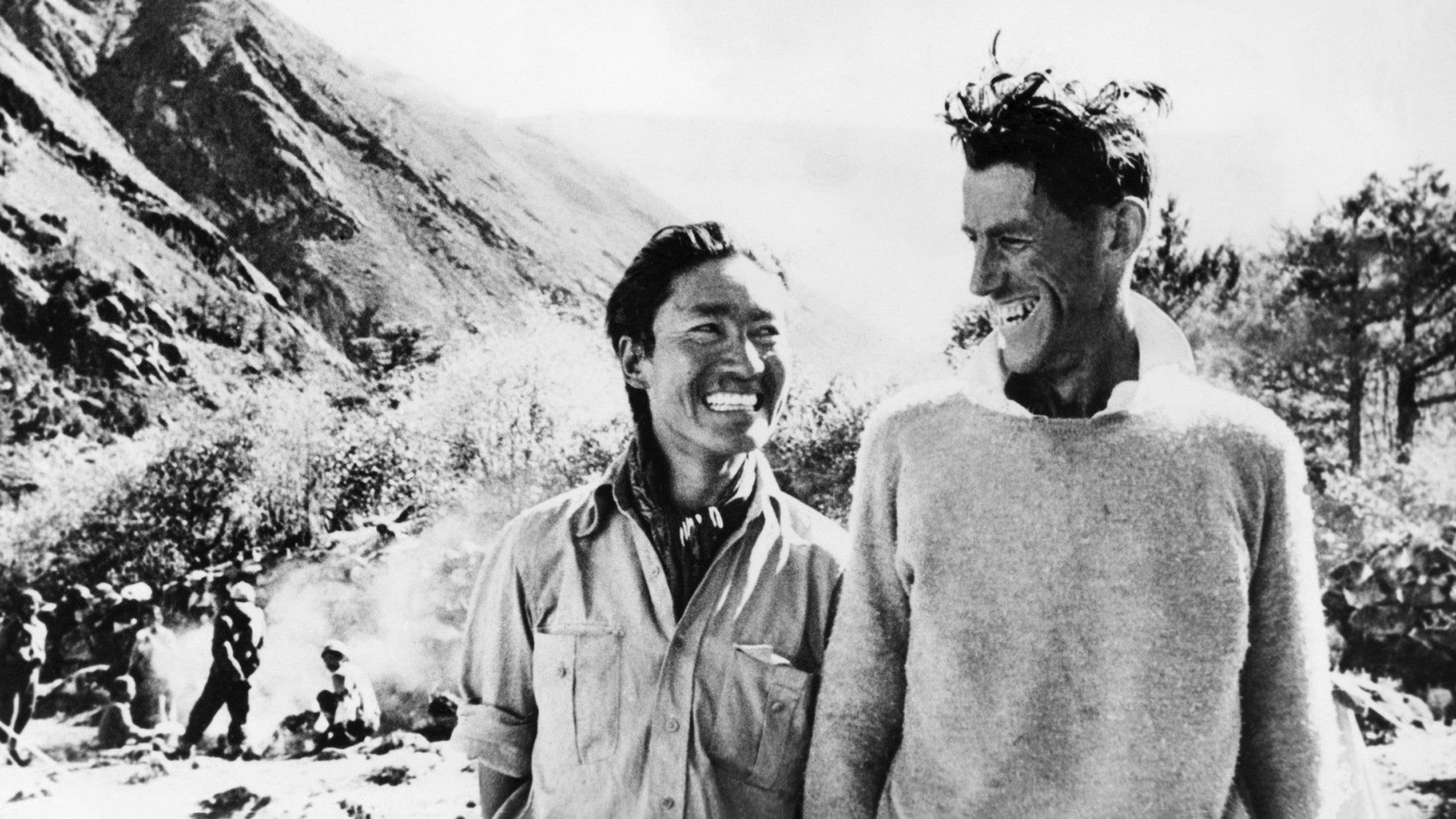

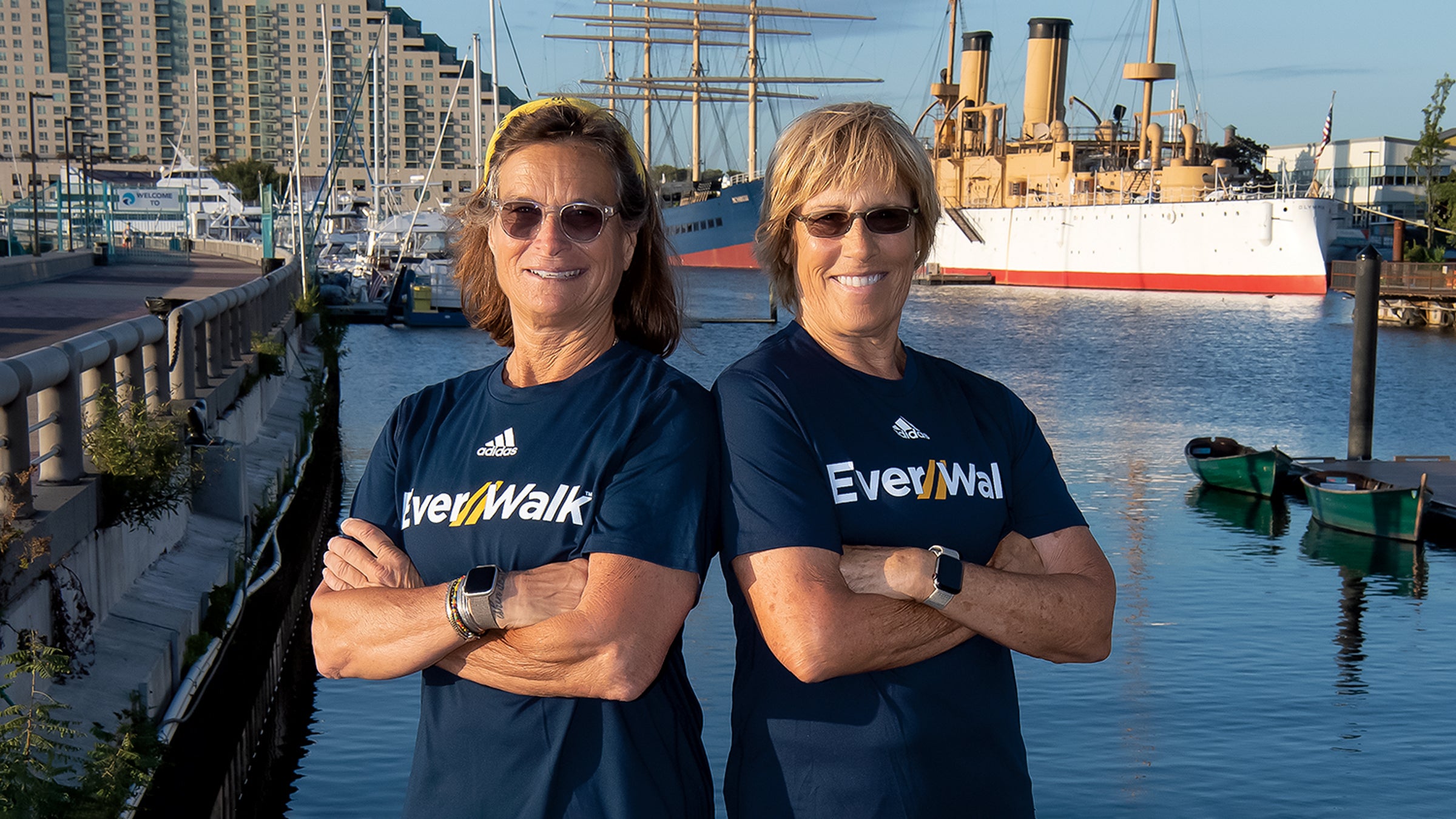

The trusty companion of trail and tent is an idea—almost a romantic longing—that haunts the world of outdoor exploits. You think of famous climbing partnerships like Conrad Anker and Jimmy Chin, or Tommy Caldwell and Alex Honnold. If you’re me, you think of writers like William Finnegan, in his surfing memoir Barbarian Days, cavorting around the globe with his buddy Bryan Di Salvatore. Finnegan once evinced the bromance aspect of the whole thing. “You go to extreme lengths, and you do it together, so these friendships really get tested,” he told Alta Journal. “You want that great wave, but it’s much greater if your friend sees you get that great wave. It’s a dense sort of homoerotic world you live in.” The same, of course, can be true of female adventure friendships.

I’m not alone in my hunger for shared adventure. You see it on the partner boards at shops like Denver’s Wilderness Exchange, where people put up cards listing their preferred pursuit and available dates (“Always,” being my favorite). You see it in endless online queries from people new to a town who don’t have anyone to join them in the outdoors. The URL adventurebuddy.com will take you to a site, based in Alaska, looking to pair people up. “What a great idea!” one commenter wrote. “Just what Alaska needs … So many things to do, but not always easy to find the people to go with.”

Indeed.

As it turns out, I actually do have an ideal adventure buddy in mind: my friend Wayne Chambliss. Wayne—currently doing post-graduate work in London on geography, part of which involves him being “inhumed,” or buried underground—is pretty much up for anything, no matter how grueling, how ill-advised, how quasi-legal. He’s got an outdoor CV that is impressively outlandish.

All this raises a question: What, in fact, makes for a good adventure buddy?

There was the time near Utqiagvik, Alaska, that he had to outsprint a polar bear—this just after he’d taken bolt cutters to his wedding ring, chucking half of it, in some Tolkienesque rite, onto the frozen Beaufort Sea. Or the time, for lack of planning, he was forced to do a fifty-one-mile single-push circumambulation of Oregon’s Three Sisters volcanic peaks. He’s been submerged in a homemade submarine, along with its maker, off the coast of Honduras; he’s been airlifted into the wilds of Canada for a kayaking trip, without much knowing how to kayak. He’s crossed the Grand Canyon from rim to rim to rim, walked through Chernobyl’s zone of exclusion, and traversed Death Valley on foot (twice). Wayne is also a ferocious magpie of information, an endless spinner of theories and weaver of connections, a writer of feverish, private dispatches. Once, when I was asked him for any off-the-cuff thoughts for a potential story on treasure, he responded immediately:

“Hey, Tom. An interesting question. I’ll give it some thought. In the meantime, are you considering botanical rarities like ghost orchids or Pennantia baylisiana, or last surviving speakers of languages, or the gold that Rumiñahui ordered hidden in the Llanganates Mountains, or the Nazi gold hidden in Lower Silesia, or the one viable REE mine in the U.S. (now owned by a Chinese concern), or how antimatter (of which less than twenty nanograms have been produced thus far, I believe) costs ~$62.5 trillion per gram, or the lone copy of Once Upon a Time in Shaolin (which would be a great opportunity to interview the Wu-Tang Clan, and maybe Bill Murray), the disassembly of the Codex Leicester…”

I will cut it off there. But it went on. And it was the first of three emails. Suffice it to say, we could spend weeks on an outing without running out of things to talk about. There is just one problem in all of this: Wayne and I have never actually done any adventures together. Our failure to connect can be explained away by that tangled alchemy of time pressure, work commitments, having a family, and the general financial state of the creative precariat. Call it real life.

The closest we got was when I randomly discovered we were both in Quito, Ecuador, at the same time. I was working on a magazine piece about a spate of new luxury high-rises built by big-name architects. He was climbing Cotopaxi, the active volcano that shimmers distantly over the city. Flopping on my bed at night after another lavish, wine-heavy dinner, I felt a bit trapped, like Martin Sheen’s character in Apocalypse Now, stewing in Saigon: “Every minute I stay in this room, I get weaker.” Wayne was out there in the bush, getting stronger.