Last week my guiding season kicked off in the beautiful—but soggy and unseasonably cold—mountains of West Virginia, with four three-day, two-night, learning-intensive courses on backpacking fundamentals.

Based on the conditions assessment that we performed during the planning curriculum, we expected rain and cool temperatures. But I was hoping for better weather than what we got: five consecutive days of precipitation and temperatures in the thirties and forties for the second trip.

Despite the adverse conditions, these trips went spectacularly. Here are some of the things that made the biggest difference.

Group Tarps

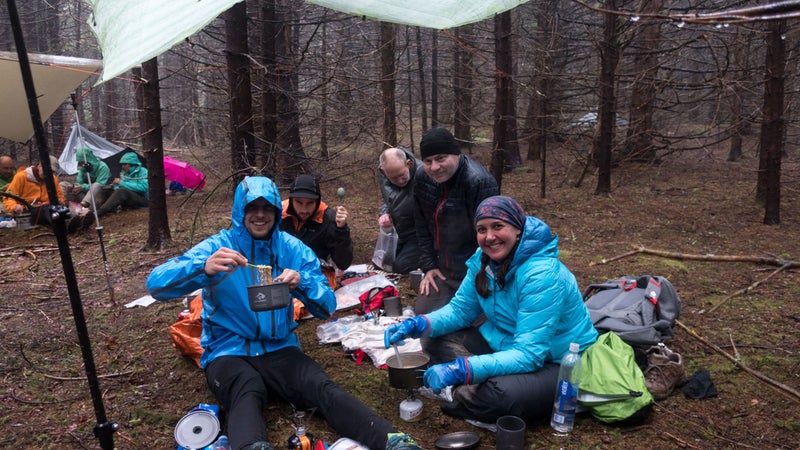

At each campsite, we created large protected spaces using oversize tarps. These had the same magnetic pull as a campfire—they allowed clients to eat, relax, and converse as a group instead of being stuck in individual shelters.

I carried two flat tarps for my ten-person groups: the Mountain Laurel Designs SuperTarp ($380), made of Dyneema composite fabric, and a Warbonnet Mamajamba ($140), made of silicone-impregnated nylon. Each weighs 12 ounces. I used ten-foot guylines on the six tie-outs; where possible, I anchored the tarps to tree trunks, sturdy branches, and exposed roots rather than stakes (per my recommended guyline system).

Campfires

In some locations and during some seasons, campfires are rightfully pooh-poohed. But fire restrictions where we were in the Spruce Knob–Seneca Rocks National Recreation Area are relatively lax, since there’s ample combustible fuel and normally a low wildfire risk.

We had campfires each night during the colder second session to warm up, dry out, and boost morale. It was also an opportunity to conduct a master class in fire starting. Unfortunately, fires are needed most in the same conditions when they’re most difficult to start—when it’s cold, wet, and windy.

On the first night, I successfully used my standard method, with a Bic lighter and Mylar food wrapper. But on the second night, we needed more help, since it’d rained most of the day and we had camped at 4,200 feet atop Spruce Knob, which had been in the clouds for days. Coghlan’s Fire Sticks ($6, two ounces) proved enormously helpful, giving us a long-burning flame that dried out and eventually ignited our kindling.

Shell Jacket and Umbrella

When it became apparent that we’d see rain, I was excited that I’d be able to test the Gore H5 Gore-Tex Shakedry jacket ($380, eight ounces). But I also wisely packed a My Trail Company Chrome umbrella ($40, eight ounces), which I’ve been wanting to thoroughly test as well.

In cool and wet conditions at least, I found the combination of these products to be stellar; they are not mutually exclusive. The umbrella kept me mostly dry—it shielded me from a lot of rain, including most of the the heaviest downpours. But the jacket was also essential; it protected my arms from driving rain, which translated into warmer hands, and I relied on it exclusively when the umbrella became impractcal, like on overgrown trails, during brushy bushwhacks, in high winds, and when the muddy trail demanded two trekking poles.

Showa Gloves

The Showa 282 gloves are among the best $20 purchases that I’ve ever made, a sentiment now shared by many of my clients and other guides. My hands used to struggle badly in cold and wet conditions, but they’ve done much better since I discovered the 282’s. On this trip, they were ideal for hiking during the day, collecting firewood in camp, and packing cold, wet tarps into stuffsacks in the morning.

These gloves feature a waterproof-breathable polyurethane shell and an acrylic liner. The shell is very tough and mildly textured (for enhanced grip). The acrylic liner is cheap and should be removed completely after it starts to delaminate. I now pair the 282 shells with Outdoor Research PL 400 Sensor gloves. If your hands are small enough, you might be able to simply buy the linerless Showa 281 version—but size way up, since they’re not designed with the expectation that you’ll wear liners with them.

Bread Bags

On the first day of each trip, my shoes were dry for about a mile—until reaching an unbridged creek, an unavoidable bog, or tall rain-soaked grass. For the rest of the trip, my shoes were at least damp and often soaked. So-called waterproof shoes would not have helped. Water would have entered from the top or just quickly overwhelmed the waterproof-breathable fabric. So instead I was left managing the effects and aftermath of wet feet.

In camp this meant having dedicated camp footwear so that we could avoid wearing cold, wet shoes for several hours before bed. Some clients brought lightweight slide sandals, but most of us packed bread bags. After arriving in camp, we removed our wet shoes and hiking socks and briefly let our feet dry. Then we’d put on our dry sleeping socks followed by bread bags, before sliding our feet back into our wet shoes. This system is remarkably effective and comfortable, in addition to being free and lightweight (about one ounce).

Fantastic Groups

OK, this is where I will get mushy.

Even with all the right gear (and the oversight of a world-class guide roster), these trips still could have been a bust. Understandably, it’s difficult to get excited about spending three days outside in inclement weather and whiteout conditions.

But our groups rocked it. For the entirety, they were positive, cheery, and engaged. They were undeterred by the cold and rain, generous with each other, and asked questions and undertook the voluntary challenges that will make them better backpackers.

Since 2011, I have guided over 80 groups. Most have been great, but not all groups would have handled themselves as well. I hope to see many of these alumni again—they are all-stars.