Laval St. Germain lives a life straight out of a novel. Traveling the world for both work and play, the 50-year-old has navigated massive peaks, deep oceans, and frozen tundra. He’s rowed a boat from Canada to France, climbed and skied the highest mountain in Iraq, and pedaled a fat bike 745 miles across the Arctic. Even that name—Laval St. Germain. It’s almost too good to be true.

St. Germain’s full-time job helps him conduct these crazy feats and explore the far corners of the globe. “When I was 11 or 12, my dad noticed I read a lot of National Geographic,” St. Germain says. “He said if I really wanted to see those places in the magazines, I should become a pilot. So I did.” He started studying for his license when he was 15 and was flying floatplanes and forest-fire-control planes in northern Canada by the time he was 17, what he describes as “the typical Canadian bush-pilot life.” At 21, he started working for Canadian North Airlines, a position that not only requires him to fly all over the world but also grants him several days off between on-duty stretches—time he uses to train and knock out extensive solo expeditions.

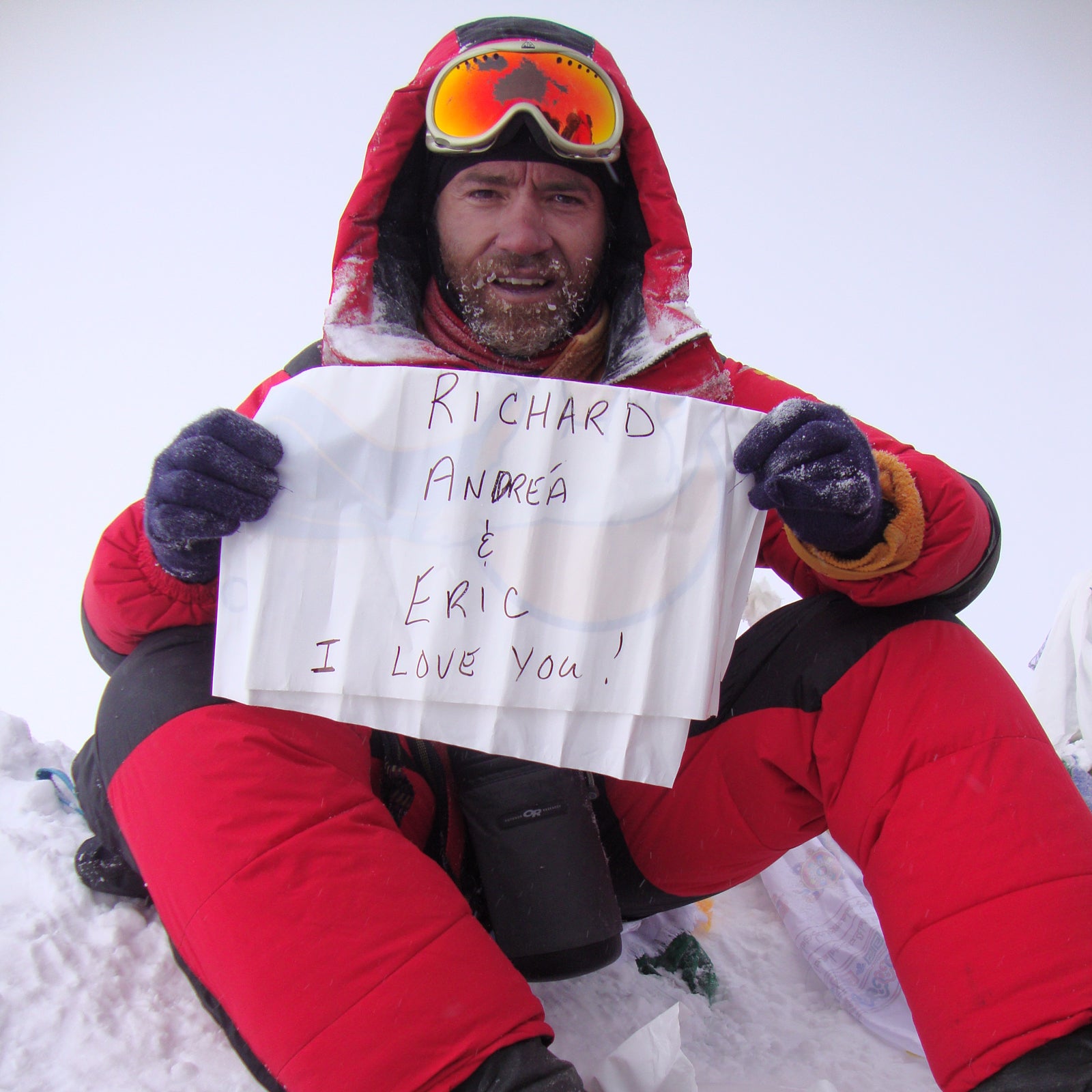

Aside from offering sage career advice, St. Germain’s father also sparked his longing for exploration, feeding him classic books like Tarzan, Moby Dick, and White Fang when he was a kid. In the past three decades, St. Germain has used this passion to build a thick adventure résumé. He was the first Canadian to climb Mount Everest without supplemental oxygen, working his way up the Tibetan side in 2010. He’s scaled the highest peak on all seven continents and trekked across fields of land mines to summit and ski Iraq’s tallest peak, 11,847-foot Cheekha Dar.

Yet these thrilling adventures don’t always go as planned. First example: he lost three fingers on his right hand to frostbite while summiting Everest. However, St. Germain insists that having those fingers amputated “wasn’t a big deal. Once you freeze it, you can’t feel it.” In November 2018, he attempted to ski to the South Pole and climb Antarctica’s tallest peak, 16,050-foot Mount Vinson. But his sled, warped due to a manufacturing flaw, kept taking a hard right turn every time he tried to ski forward, forcing him to quit 13 days and 124 miles into the projected 745-mile cross-country trip. St. Germain ditched the faulty sled and went ahead and climbed Mount Vinson but will have to go back to finish skiing across the continent before he can close the book on that expedition. He’s hoping to return next year.

Even that name—Laval St. Germain. It’s almost too good to be true.

Despite overcoming these obstacles, St. Germain says the adventures he’s most proud of are the ones that didn’t make the papers. “I look back on some of the tough trips my wife, Janet, and I took with our kids before they were even teens and am amazed we pulled them off,” St. Germain says. “A multi-day bike tour across the Arctic above tree line with grizzly bears and black flies, taking them to Namibia to climb in the desert, or to Guyana to explore one of the last-frontier rainforests in the world. Showing our kids they can do tough stuff in the outdoors, that’s what I’m most proud of.”

St. Germain and his wife put a lot of energy into instilling a sense of adventure in their children, just as his own father did for him. Tragically, the couple lost their oldest child, Richard, to a canoeing accident on the Makenzie River in Canada five years ago. He was just 21 and beginning his own career as a bush pilot. “The outdoors has given us a lot as a family, but it’s taken a lot away, too,” St. Germain says. “It’s the toughest thing we’ve ever been through, and it’s still tough. But it reinforced my desperate struggle to cram a lot into my life. I use the outdoors as a therapy. Struggling out there, it’s cathartic.” Since that devastating event, St. Germain has used his expeditions as a way to help others. He delivered a check for $5,000 to the search and rescue team on the Mackenzie River during his long-distance Arctic fat-bike ride last spring. His row across the Atlantic raised more than $60,000 for the Alberta Cancer Foundation.

In order to stay in shape for these intense feats, St. Germain says he rarely indulges in a rest day. “Basically, I’m always training,” he says. “It’s my lifestyle more than anything.” He has never hired a coach, and while he does schedule in up to three days of weight training a week, he refuses to do cardio indoors. Instead he rides his bike nine miles to work each way, which he calls “free training,” and plans out epic combo days, where he peddles to the Rockies, stashes his bike, summits a mountain, and rides home. In the winter, he does something similar with a fat bike and telemark skis.

St. Germain also has a circuit in his hometown of Calgary that involves biking between five different sets of outdoor stairs and running five reps on each. “I love training on stairs, because it’s low impact and you get a lot of bang for your buck,” he says, adding that his greatest stair workout happened in China when he was picking up a plane for his airline. “I ran 7,000 steps cut into the side of Mount Tai,” he says. “It was like heaven.”

Currently, St. Germain is planning a 186-mile gravel ride from Calgary to Fernie, a city deep within British Columbia’s mountains. He also has a bigger expedition on the horizon that he’s reluctant to talk about because it’s in a geopolitical hot zone and the logistics aren’t set in stone. It’s likely bound to be difficult and dangerous, something that would fit into the pages of the classic literature he devoured as a child. “I love sticking my neck out and embracing discomfort,” St. Germain says. “The whole world is designed to avoid discomfort right now, but anything that’s worth doing will be uncomfortable and challenging.”