Back in the summer of 1980, the barkeep of the Neuadd Arms Hotel in the Welsh town of Llanwrtyd Wells overheard two men arguing about one of those hypothetical questions that inevitably come up after a few pints of cwrw. Who would cover a long distance over mountainous terrain more quickly, they wondered: a human or a horse? The bartender, a man named Gordon Green, was intrigued—and the event he set up, a 22-mile challenge known as the Man Versus Horse Marathon, has been running annually ever since.

The answer, it turns out, is that horses are pretty clearly faster, at least under the conditions that Green created. Only twice in the race’s history has a human triumphed. The first time was in 2004, when Huw Lobb—a former college teammate of mine, as it happens—finished in 2:05:19 to edge out a horse named Kay Bee Jay by just over two minutes. Lobb was no slouch: he was a cross-country ace who ran a 2:14 marathon the following year. He collected a cool 25,000 British pounds (about $45,000 at the time), because the pot had been growing by 1,000 pounds a year since the race’s inception, waiting for the first human winner.

(Aside: that year’s edition of the race also featured the unveiling of a memorial to Screaming Lord Sutch, the founder of Britain’s Monster Raving Loony Party, who was the event’s official starter until his death in 1999. Now you know.)

Lobb’s victory came on a hot day, as did Florian Holzinger’s subsequent victory in 2007—a significant detail, according to a new study in the journal Experimental Physiology from Lewis Halsey of the University of Roehampton in Britain and Caleb Bryce of the Botswana Predator Conservation Trust. Halsey and Bryce gathered historical data from three endurance races that pit humans against horses, including the Man Versus Horse Marathon, to test the idea that humans are uniquely adapted to run for long distances in hot weather.

This idea has been around since the 1980s, and it gained prominence when Harvard anthropologist Daniel Lieberman and University of Utah biologist Dennis Bramble published a 2004 Nature paper hypothesizing that running had “substantially shaped human evolution.” They argued that our ability to keep running at a moderate pace even on hot days allowed us to run prey like kudu to exhaustion or outcompete other animals in the race to scavenge carcasses left by other large predators.

In addition to gaining a bunch of anatomical features suited for running, like springy leg tendons and a big heel bone for better shock absorption, we also lost most of our fur and developed the ability to sweat copiously. In fact, Halsey and Bryce note, we’re “probably the most perspirative of all species,” which allows us to get rid of heat more quickly.

This “born to run” theory, and the associated narrative about the evolutionary importance of persistence hunting, are pretty well-known. In fact, I wrote an article about persistence hunting among the Tarahumara just a few weeks ago. But it turns out that not everyone in the scientific community buys the idea that we’re uniquely evolved to chase big game. Halsey and Bryce sound a note of skepticism about “this claimed capacity” for running in hot weather, noting that lots of other species, including horses and dogs, are way better at running long distances and have far more impressive cardiovascular systems than we do.

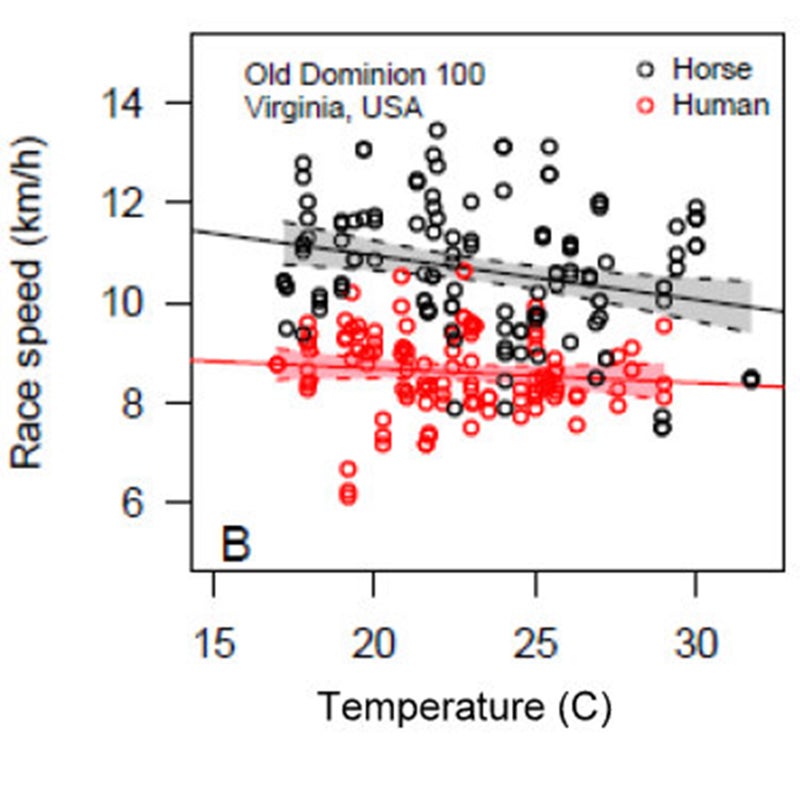

The question they set out to test was not whether humans are better than horses in this capacity (they nearly always aren’t) but whether they’re relatively better as the weather gets hotter. They looked at three races: the 22-mile race in Wales; the Western States 100-miler (for humans) and the Tevis Cup 100 (for horses) in California; and the Old Dominion 100-miler in Virginia. The latter two have had separate races over the same course for humans and horses since the 1960s or 1970s, so the Welsh race is the only true head-to-head battle.

For each of these races, Halsey and Bryce obtained records from nearby weather stations. Then they plotted the average speed of the top three humans and the top three horses for each year, as a function of race-day temperature. For both humans and horses, hotter temperatures led to slower times. But the trend was significantly steeper for horses than for humans.

Here, for example, is the data from the Old Dominion 100, with humans in red and horses in black:

Overall, for every increase of 1 degree Celsius (1.8 degrees Fahrenheit), the horses slowed down by about 1 percent—or 0.07 miles per hour, to be precise. The humans, on the other hand, slowed down by just 0.04 miles per hour for each extra degree of heat. That 36 percent advantage for the humans was statistically significant.

So, yes, compared to other mammals adapted for running long distances, humans seem to be particularly good at handling heat. But they still lose to horses nearly every time, and would lose by even larger margins on flat terrain. Halsey and Bryce call out a quote from a recent Lieberman paper—“no horse or dog could possibly run a marathon in 30 degree [Celsius, or 86 Fahrenheit] heat”—as “demonstrably untrue,” citing examples such as a wandering dog named Cactus who completed a substantial portion of last year’s Marathon des Sables on a canine whim.

Our real superpower, they end up arguing, is our brain. “Rather than being the elite heat-endurance athletes of the animal kingdom,” they write, “humans are instead using their elite intellect to leverage everything they can from their moderate endurance capabilities.” The tiny advantage our ancestors got by hunting during the hottest part of the day only paid off when it was coupled with shrewd assessments of where the prey was headed next and sophisticated communication among cooperative group members. We were like poker players counting cards in a casino, using our brainpower to profit from an infinitesimal edge.

Still, for all their skepticism about the evolutionary importance of persistence hunting, Halsey and Bryce’s new results do support the hypothesis. When the going gets hot, we get relatively better. So as the summer heat intensifies, bear this little nugget of good news in mind. At least you’re not a horse.

For more Sweat Science, join me on Twitter and Facebook, sign up for the email newsletter, and check out my book Endure: Mind, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human Performance.