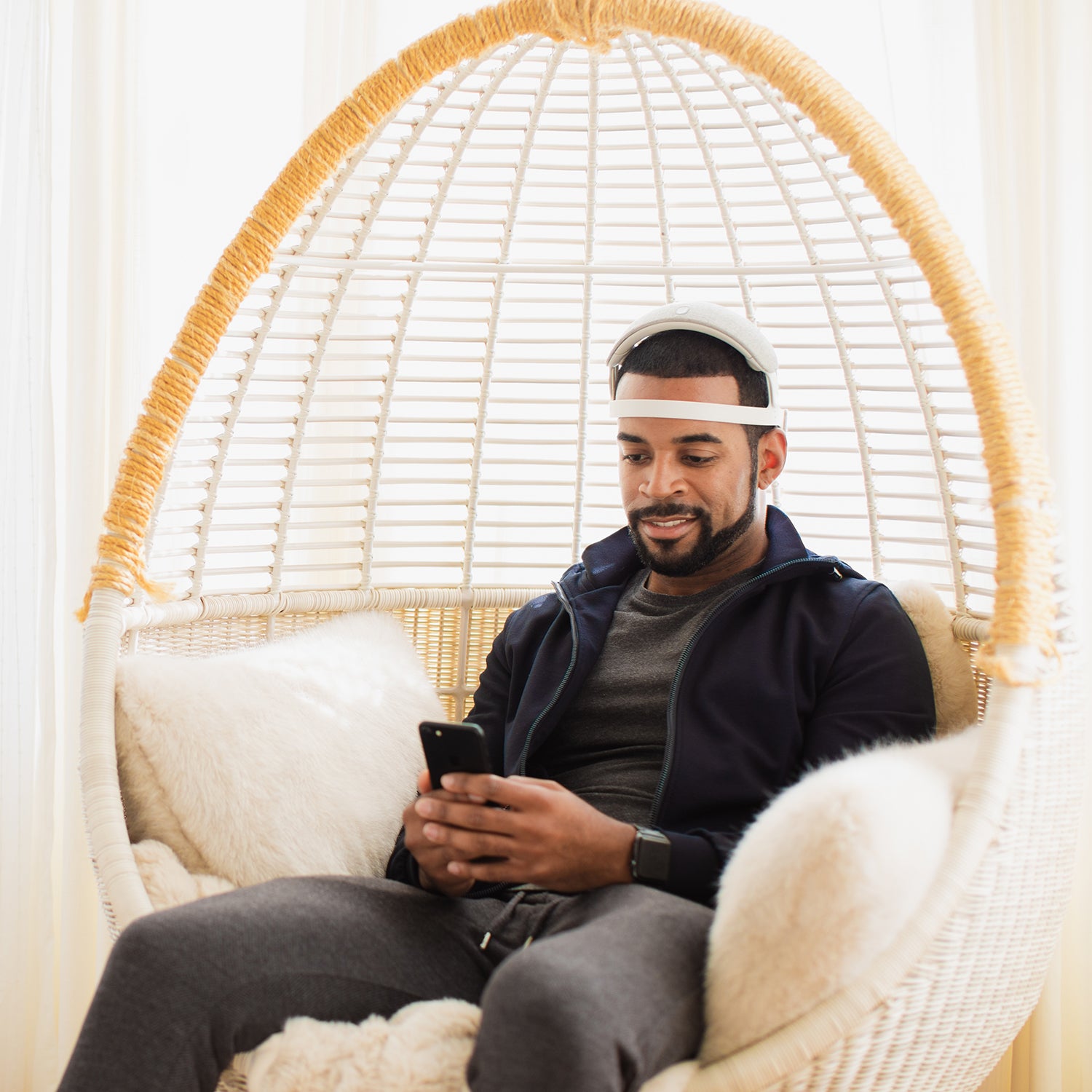

I’m sitting in my desk chair, staring at a group of jellyfish on my phone, and wearing a neurofeedback device called URGOnight ($499), a bulky white headband fitted with four gold electrodes that runs across my forehead, on top of my head, and behind my ears. Occasionally a jellyfish disappears from my phone screen and a little happy piano note sounds—my “reward” ping. I’m confused. I like sea jellies. Why would I want them to disappear? I try staring around my room. I glance at a poster about soil types—ping. A tree outside my window—ping. Back to the poster—ping. I look at the tree again, but this time there’s no reward.

The purpose of this exercise is to make me a better sleeper. While falling asleep is relatively easy for me, the smallest disturbance in my house rouses me again: footsteps, a door closing, the floor creaking. I do what I can to accommodate my light slumber—I only drink coffee in the morning, and I use blackout curtains, a white-noise machine, and earplugs—but I still can’t avoid sudden awakenings, which sometimes result in starting my day at 4 A.M. It’s led to housemate strife, anxiety, and many, many, long nights.

All of my efforts to sleep better thus far have been about adjusting to my environment. But what if I could teach myself to become a deeper sleeper instead? That’s where the URGOnight comes in.

The funky-looking headband made by the company URGOtech is essentially an at-home electroencephalogram (EEG) machine. An EEG tracks the electrical activity in our brains, measuring the frequencies in hertz. The ups and downs of the signal can show what’s happening in the brain and are used to classify the different stages of sleep. Generally, a higher frequency suggests greater alertness.

The URGOnight focuses on sensorimotor-rhythm (SMR) waves, or low-beta waves, which fall in the 12-to-15-hertz range. While wearing the headband, the linked phone app rewards users with little pings and animations when they produce waves in that range. The idea is that those cues help you understand how to produce more SMR waves when awake, which hypothetically leads to greater production of sleep spindles—brief squiggles in the 10-to-15-hertz range that are thought to be associated with memory processing during sleep—while asleep. URGOnight customers are encouraged to use the device at least three times a week, and the company says that many people begin to experience better sleep after 15 to 20 sessions.

A 20-minute session in the app is split into five chunks of training, with one-minute breaks in between. The app offers some suggestions on what to do to produce more SMR brainwaves, including focusing on breathing, clearing the mind, or thinking positive thoughts. But mainly, it leaves it up to users to figure out their own strategy.

I tried a few animations during my first sessions. The jellyfish one made me sad, but zooming through galaxies was more satisfying; the more SMR waves I made, the closer I got to the stars. I tried concentrating on the app or on other sights around me, clearing my head, breathing, and stretching (the last is not recommended by the company, as muscle movement also creates electric signals that can disrupt EEG accuracy). My feedback scores for the sessions varied wildly. On a scale of one to 500, I’d go from 150 in one session, to 309 the next, and then back to down to 139 after that. (There isn’t really a good score, according to the company—your feedback numbers are based on how much you’re able to increase your SMR waves compared to a baseline measurement at the start of the session.)

URGOtech says it has the data to prove that, over time, training with the device will reward users with more restful sleep. In March, researchers funded by URGOtech published a clinical study in which they instructed 37 participants with insomnia to use the device four times a week for a total of 40 or 60 sessions. The patients filled out questionnaires on their sleep quality before receiving an URGOnight, midway through the treatment, at the end, and three to six months after the trial. By the end of the treatment, self-reported sleep time went up by 30 minutes on average for all users, and up another 12 minutes in the following months. Significant sleep gains were confined to the 11 individuals who were able to consistently increase their SMR waves during sessions, resulting in a self-reported hour increase in sleep time, on average.

To the research team, that’s a success. Martijn Arns, the founder of Research Institute Brainclinics and senior author of the paper (which has not yet been peer-reviewed), said the trial shows that the treatment is “very feasible.” He found the study’s results to be a promising indication of the effectiveness of SMR treatments and noted that no one treatment for sleep works for everyone.

Others aren’t convinced. Robert Thibault, a researcher at the University of Bristol, in the UK, pointed out the lack of a control group and the direct involvement of the company seeking to profit off the product, which can bias results. Philip Gehrman, a clinical psychologist focused on sleep medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, was also not impressed: “This is a minuscule improvement [in sleep],” he says.

It’s not the only neurofeedback sleep study to be met with misgivings. Some researchers who have done the very work that URGOtech cites to support its product have doubts about the neurofeedback treatment. Aisha Cortoos, a sleep psychologist who founded a private practice focused on non-neurofeedback sleep interventions, called Brainwise, previously studied the effectiveness of SMR training for sleep. Although she has seen positive results in her research, she’s still a bit skeptical about whether neurofeedback can actually train better sleep, mostly because there aren’t a lot of large studies looking at the practice. Neurofeedback is a “dirty tool,” she adds, because so many factors can affect the reading, such as the thickness of your scalp, your age, even blinking. SMR training has also yet to demonstrate a “clear link” to increased sleep spindles at night in humans, she says. “It’s still based on hypothetical links.”

Very few, if any, sleep studies employing a rigorous design—one that is double-blind and placebo controlled—have noted a significant benefit to neurofeedback therapy, says Thibault. One of the few that did meet that standard saw no significant benefit in neurofeedback over a sham treatment.

With millions of Americans struggling with inadequate sleep and escalating stress, it’s easy to see why products like URGOnight command such interest—they’re convenient, and they have the appearance of fancy medical technology. The promise of a quick fix to calm our minds, or train them to sleep better, sells: the sleep-aid market exceeded $81 billion in 2020, according to the firm BCC Research. The trouble is that many high-tech sleep and relaxation tools out there fail to provide robust evidence for their efficacy.

That doesn’t mean people don’t experience real benefits from these neurofeedback treatments. Personally, I started recording fewer nighttime awakenings and deeper sleep after around 15 sessions with the headband. But the reason why people like me benefit might have more to do with a placebo effect, or so-called psychosocial influences. Interacting with doctors, flashy tech, and undergoing a pricey treatment are all factors that have been shown to increase our expectation of improving psychological symptoms. And that expectation itself can have a powerful effect on our mental state, Thibault wrote in a review of consumer neurofeedback devices. “Insomnia studies tend to have big placebo effects,” says Gehrman. “People with insomnia tend to be anxious and worried about their ability to sleep at night, and that makes it harder to sleep. But if I tell you, ‘I’m going to give you this treatment, and it’s going to help you sleep better,’ people tend to be more relaxed, which helps them to sleep better.”

There are still gaps in our understanding of how neurofeedback works. But Arns says that’s true of most clinical treatments, and he doesn’t think that should preclude selling these products because they have little to no adverse risks associated with them. “I mean, there might not be physical risks associated with it,” says Gehrman. “But there are monetary risks.”

Arns also pushes back on the traditional view of placebos—that either a treatment works as proposed or it’s wholly ineffective. He says that individuals can experience benefits for multiple reasons, making neurofeedback’s effect tricky to disentangle from everything else affecting our brains. In the URGOnight study, patients continued to sleep better three to six months after the trial. That long-lived benefit is telling, says Arns. “If you provide a placebo pill for depression, that has a short-lived effect—the depression will soon catch up with people again,” he says (although some recent research calls that into question). “From a clinical perspective, I think the most important thing is that the effects are lasting.”

Yet the gold-standard treatment for insomnia remains cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia, or CBT-I. Cortoos, the sleep psychologist, explains that your brain essentially seesaws between its sleep and wake system. From an evolutionary perspective, sleep is dangerous: feeling stressed signals that there’s a threat, and that you must remain awake and vigilant. “This is what’s going wrong with insomnia patients,” says Cortoos. The wake side of the seesaw in insomniacs is heavily weighed down.

CBT-I rebalances that seesaw. It uses tools like deliberate sleep restriction to weigh down the sleep side while teaching patients how to build constructive thoughts around sleep and use calming exercises to lighten the stress side. This program, which typically runs six to eight weeks and costs anywhere from a few hundred to over a thousand dollars, has been found effective in about 80 percent of patients, according to Cortoos. Further, many insurance plans cover it, says Gehrman. (Though if you have the cheapest-possible, high-deductible plan like me—or no coverage—paying for it may not be so easy.)

As I learned more about the limited evidence behind neurofeedback tools like URGOnight, I grew increasingly averse to setting aside my work five times a week to stretch the electrodes over my head, sit down, and stare at the app. Still, I continued to try breathing techniques and clearing my mind. I watched as bubbles burst and icebergs swished around. And I did start to sleep better, even sometimes snoozing through the entire night.

I’m not sure how often I’ll don the URGOnight band in the future. I’m reluctant to commit my time to a questionable technology. But I say that now, while I’m enjoying a phase of relatively sound sleep. Even though the benefits I experienced could have been pure placebo, using this device taught me that sleep is malleable—that there’s hope for my weary, anxious, and pandemic-addled brain. Perhaps I’m sleeping better just knowing that.